By Jonathan Photius — the Neo-Historicism RESEARCH Project

Abstract

Pantazès of Larissa, an eighteenth-century Greek interpreter of the Apocalypse, stands at a pivotal juncture in the evolution of post-Byzantine Orthodox eschatology. His writings—produced during the period of intense political upheaval caused by the Russo–Turkish wars—blend scriptural exegesis, Byzantine prophetic tradition, and contemporary geopolitics. This article examines Pantazès’ life and intellectual context, analyzes his unique eschatological system (notably his “three Antichrists” doctrine), compares his method with earlier and later Greek historicist commentators, and evaluates his influence on subsequent Orthodox approaches to the Apocalypse.

1. Introduction

Pantazès of Larissa occupies a distinctive position in the development of Greek Orthodox apocalyptic commentary in the post-Byzantine and early modern periods. Writing in the late eighteenth century during the turbulence of the Russo–Turkish wars, Pantazès crafted an interpretation of Revelation that merged biblical symbolism with contemporary geopolitics, selecting the Ottoman Empire, Western Europe, and Tsarist Russia as the central actors in an unfolding eschatological drama.

Unlike his predecessors, Pantazès is not primarily a theologian but a political exegete, whose interpretive framework reflects the aspirations, anxieties, and prophetic imagination of Orthodox peoples under Ottoman rule. His work, preserved and analyzed by modern scholars such as A. Agyriou, reveals the convergence of learned exegesis with popular apocalyptic oracles circulating throughout the Balkans.¹

2. Historical Background and Intellectual Setting

Pantazès lived in Bucharest, then an important intellectual center for Greek-speaking Orthodox under Phanariot rule. The late eighteenth century was marked by profound upheaval:

- the Russo–Turkish Wars of 1768–1774 and 1787–1792,

- the Orlov Revolt in the Peloponnese,

- the annexation of Crimea by Russia,²

- and Catherine the Great’s putative “Greek Project,” a political vision to restore Constantinople as an Orthodox Christian capital.³

In this environment, apocalyptic texts were not marginal curiosities but vehicles of communal hope. Scholars such as Dimaras and Politis note that prophetic literature—especially Agathangelos and the Oracles attributed to Byzantine saints—circulated widely, shaping expectations of Ottoman collapse and imperial restoration.⁴ Eschatology served not merely as theological speculation but as a political hermeneutic.

Pantazès absorbed these influences, interpreting Revelation not as a distant eschaton but as a commentary on the geopolitical conditions of his own day.

Within this environment, eschatology served not merely as theological speculation but as a political hermeneutic. Pantazès interpreted Revelation through this lived historical reality, producing a commentary deeply embedded in contemporary events.

3. Pantazès’ Eschatological Framework

Pantazès’ exegesis represents a synthesis of scriptural interpretation, Byzantine prophetic lore, and contemporary political observation.

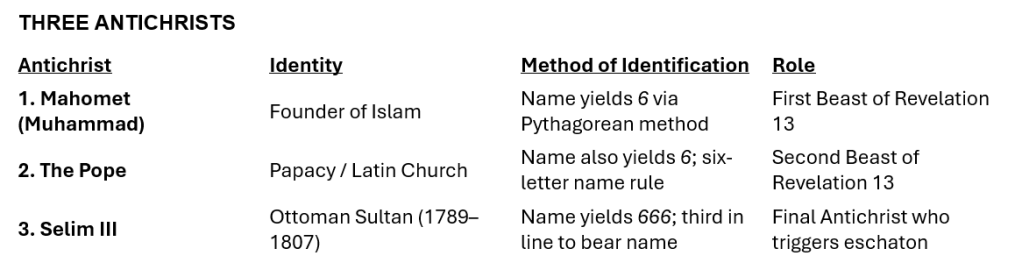

3.1. The Doctrine of the Three Antichrists

Pantazès uniquely identifies three Antichrists—Muhammad, the Pope, and Selim III—each corresponding to a stage of apocalyptic opposition.

- The identification of Muhammad and the Papacy as the two Beasts reflects the historical consensus of earlier Greek commentators such as Christophoros Angelos and Georgios Koressios.⁵

- The innovation lies in the identification of Selim III as a new and final Antichrist, justified through Pythagorean numerology and name analysis.⁶

Agyriou emphasizes that this threefold schema has no parallel in earlier Greek Orthodox exegesis, marking Pantazès as an outlier and creative interpreter within the historicist tradition.⁷

3.2. Identification of Islam and Papacy as the Two Beasts

Following the established post-Byzantine tradition:

- Islam is the First Beast of Revelation 13,

- Papacy is the Second Beast or False Prophet.⁸

This long-standing interpretation appears first in late Byzantine anti-Latin polemic and is articulated more systematically in the works of Angelos (London, 1619), Gordios (early 18th c.), and Koressios.⁹

Pantazès radicalizes the tradition by replacing symbolic antiquity with direct Ottoman and European referents.

3.3. Russia as the Eschatological Liberator

In Pantazès’ system, Russia functions as the eschatological agent of divine justice. Drawing on the oracular tradition of Tarasios, Leo the Wise, and Agathangelos, Pantazès interprets the “Blond nation” (ξάνθοι) as Russia.¹⁰

Modern scholarship (Kiousopoulou, Angelou) confirms the widespread presence of Russophilic messianism in Orthodox apocalyptic imagination during this period.¹¹

Pantazès integrates this directly into Revelation 19, identifying the Russian forces with the Rider on the White Horse—an unprecedented interpretive move in Greek exegesis.

3.4. A Chronological System Synchronizing Prophecy and History

Pantazès employs symbolic numerology, historical events, and chronological layering:

- 1453 as the starting point of the Ottoman “Beast power”

- the 300-year decline beginning in 1753

- the 313th year eclipse marking a prophetic shift

- the loss of Crimea (1783/1788) as apocalyptic sign

- the rise of Selim III (1789) as the Antichrist

- the predicted fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1803

- the 102.5-year restored Orthodox empire¹²

Though inaccurate, Pantazès’ chronology follows the historicist assumption that prophecy unfolds within real history—an approach later refined in Makrakis and Sotiropoulos.

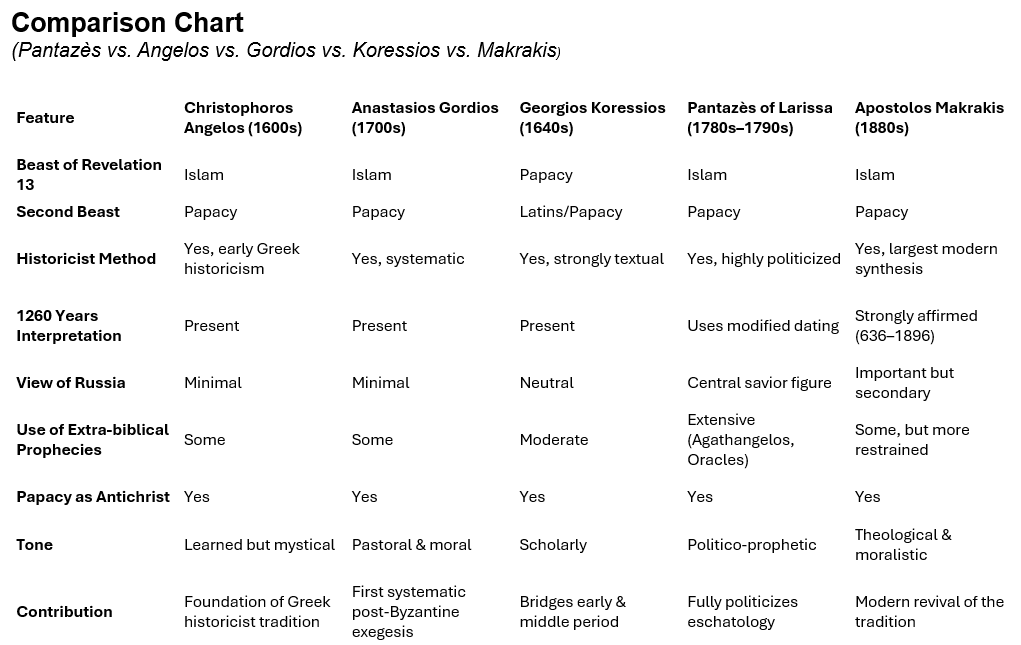

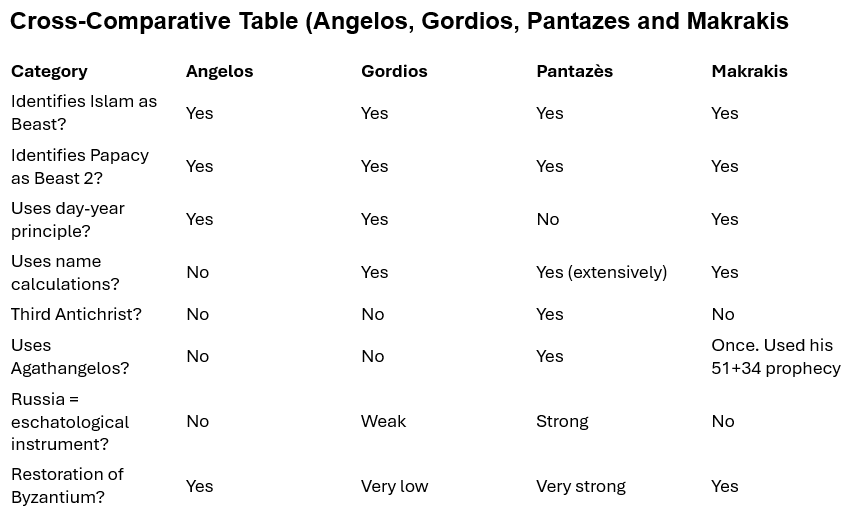

4. Pantazès and the Greek Historicist Tradition

Pantazès must be understood within the broader evolution of Greek Orthodox historicist commentary.

4.1. Christophoros Angelos

Angelos († c. 1640) introduced the earliest systematic Greek historicist reading of Islam and Papacy as the two Beasts.¹³ Pantazès inherits this but politicizes it, shifting from a theological to a geopolitical interpretation.

4.2. Georgios Koressios

Koressios (1640s) combined erudition with philosophical analysis.¹⁴ Pantazès departs from Koressios’ learned tone, adopting instead the language of prophetic nationalism.

4.3. Anastasios Gordios

Gordios († 1729) advanced historicist chronology and moral exegesis.¹⁵ Pantazès retains the chronological impulse but eliminates ethical teaching, focusing exclusively on political actors.

4.4. Apostolos Makrakis and the Modern Revival

Makrakis (1831–1905) does not cite Pantazès but inherits key historicist themes:

- Islam as Beast

- Papacy as False Prophet

- Day-year chronology

- Anticipation of Ottoman collapse

- Restoration of Constantinople

Makrakis’ method is theological and systematic, while Pantazès’ is political and prophetic. Yet both belong to the same unfolding arc of Orthodox historicism traced by scholars such as Agyriou and Politis.¹⁶

Pantazès thus forms a crucial bridge between early post-Byzantine exegetes and the modern revival of Greek historicist thought.

5. Pantazès’ Legacy and Theological Impact

Pantazès’ significance lies not in doctrinal precision but in his synthetic capacity:

- He reflects the eschatological psychology of Orthodox communities under Ottoman rule.

- He integrates biblical, Byzantine, and popular prophetic traditions.

- He models how Revelation was used as a political hermeneutic rather than speculative futurism.

His writings help modern scholars understand the lived eschatology of eighteenth-century Greeks—where prophecy, suffering, national identity, and hope were inseparable.

6. Conclusion

Pantazès of Larissa stands as a seminal figure in the transition from early post-Byzantine apocalyptic speculation to later, more structured Orthodox historicism. His unique contributions—the threefold Antichrist doctrine, the integration of Russian messianism, and his harmonization of Revelation with contemporary events—render him indispensable to any study of Eastern Orthodox eschatological development.

His work is a testament to the creativity with which Orthodox intellectuals interpreted history through the lens of prophecy, anticipating the later nineteenth and twentieth century theological and philosophical frameworks of Makrakis and Sotiropoulos.

Pantazès of Larissa represents a decisive phase in the evolution of Greek Orthodox eschatology. His readings of Revelation illustrate the dynamic interplay between prophecy, politics, and national expectation. As a bridge between early post-Byzantine commentators and later nineteenth-century theologians, Pantazès deserves renewed scholarly attention for his role in shaping modern Orthodox historicist hermeneutics.

FOOTNOTES

- A. Agyriou, Les Exégèses Grecques de l’Apocalypse à l’Époque Turque (1453–1821) (Thessaloniki: San Studio, 1982), ch. on Pantazès.

- See D. Kiousopoulou, The Fall of Constantinople in 1453: Memory and Interpretation (Athens: MIET, 2011).

- On Catherine II’s “Greek Project,” see M. Raeff, Russia Abroad (Oxford University Press, 1990).

- K. Th. Dimaras & L. Politis document the persistence of Agathangelos and prophetic oracles in Greek popular consciousness.

- For Angelos’ anti-Islam and anti-Latin analysis, see N. H. Angelou, Christophoros Angelos: A Greek Intellectual Between East and West (Leiden: Brill, 1992).

- Agyriou, Les Exégèses, pp. 373–390.

- Ibid.

- This dual identification appears consistently from the late Byzantine period onward.

- G. Koressios’ writings reflect early scholastic historicism.

- The ξανθοί motif appears in Tarasios’ Oracle and Agathangelos.

- D. Kiousopoulou & P. Angelou discuss Russophilic currents in early modern Orthodoxy.

- Agyriou’s analysis provides the internal logic of Pantazès’ chronology.

- Angelou, Christophoros Angelos, ch. 5.

- Koressios’ philosophical method contrasts strongly with Pantazès’ prophetic approach.

- Gordios’ commentary incorporates ethical exhortation absent in Pantazès.

- Dimaras, Politis, and Agyriou trace the genealogy of Greek historicism through these figures.

© 2025, Jonathan Photius