By: Jonathan Photius, The NEO-Historicism Research Project

Abstract

Cyril (Kyrillos) Lavriotis of Patras (1742-1829) occupies a distinctive yet understudied position within the post-Byzantine Greek Orthodox tradition of apocalyptic exegesis. His extensive, unpublished 1817 AD commentary on the Book of Revelation—preserved in multiple manuscript witnesses—represents a mature synthesis of Byzantine symbolic interpretation and early modern Orthodox historicism. This article reconstructs Lavriotis’s hermeneutical method, ecclesiology, eschatology, and prophetic chronology on the basis of Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse, situating him within a continuous Orthodox lineage extending from late Byzantine commentators through Christophoros Angelos and culminating, in refined form, with Apostolos Makrakis. Particular attention is given to Lavriotis’s application of the 1260-year prophetic period to Islamic domination, his use of retrospective chronology, and his rejection of speculative futurism. The study argues that Lavriotis represents a fully Orthodox form of historicist apocalyptic interpretation—here designated Neo-Historicism—independent of later Protestant systems and grounded in ecclesial, conciliar, and historical consciousness.

I. Biographical Introduction: Cyril Lavriotis of Patras

Cyril Lavriotis of Patras was a Greek Orthodox monk, exegete, and theologian active in the late seventeenth to early eighteenth century, best known as the author of a monumental, eight-volume commentary on the Book of Revelation. Although the precise details of his life remain fragmentary, surviving manuscript evidence and later scholarly testimony allow for a reasonably clear reconstruction of his ecclesiastical and intellectual milieu.

The epithet “Lavriotis” strongly suggests an association with the Great Lavra Monastery on Mount Athos, whether through monastic profession, theological formation, prolonged residence, or manuscript affiliation. In post-Byzantine usage, such designations were commonly applied not only to monks permanently tonsured at a particular monastery, but also to those who had received their education, spiritual formation, or scribal training within that monastic environment.¹¹ The Athonite character of Lavriotis’s work—its ascetical tone, liturgical sensitivity, Christocentric symbolism, and deep familiarity with Byzantine exegetical authorities—provides further internal confirmation of this connection.

At the same time, Lavriotis is also identified as “of Patras,” indicating either his place of origin or his later ecclesiastical activity. Patras, during the post-Byzantine period, functioned as a significant theological and intellectual center, closely linked to Athonite monastic networks and to the wider Greek Orthodox scholarly diaspora under Ottoman rule. Lavriotis thus appears to belong to a broader Western Peloponnesian scholastic culture that combined Athonite monastic spirituality with active engagement in teaching, preaching, and manuscript production.

Lavriotis’s surviving commentary on the Apocalypse—preserved in multiple manuscript copies and exceeding five thousand folio pages—attests to a lifetime devoted to study, interpretation, and theological reflection. His work displays intimate familiarity with the classic Byzantine commentators, especially Andrew of Caesarea, while simultaneously advancing a distinctly historical reading of Revelation shaped by the lived experience of Orthodoxy under Islamic domination and in conflict with Latin ecclesiastical claims.

Although no autobiographical account survives, Lavriotis emerges from his writings as a monk-scholar formed within the Athonite spiritual tradition, intellectually active within the Greek Orthodox world of Ottoman rule, and deeply concerned with the historical destiny of the Church. His synthesis of monastic spirituality, conciliar theology, and historicist apocalyptic interpretation situates him as a pivotal transitional figure between the medieval Byzantine exegetical tradition and the fully articulated Orthodox historicism of the modern period.

II. Methodological Foundations: Orthodox Historicism Reaffirmed

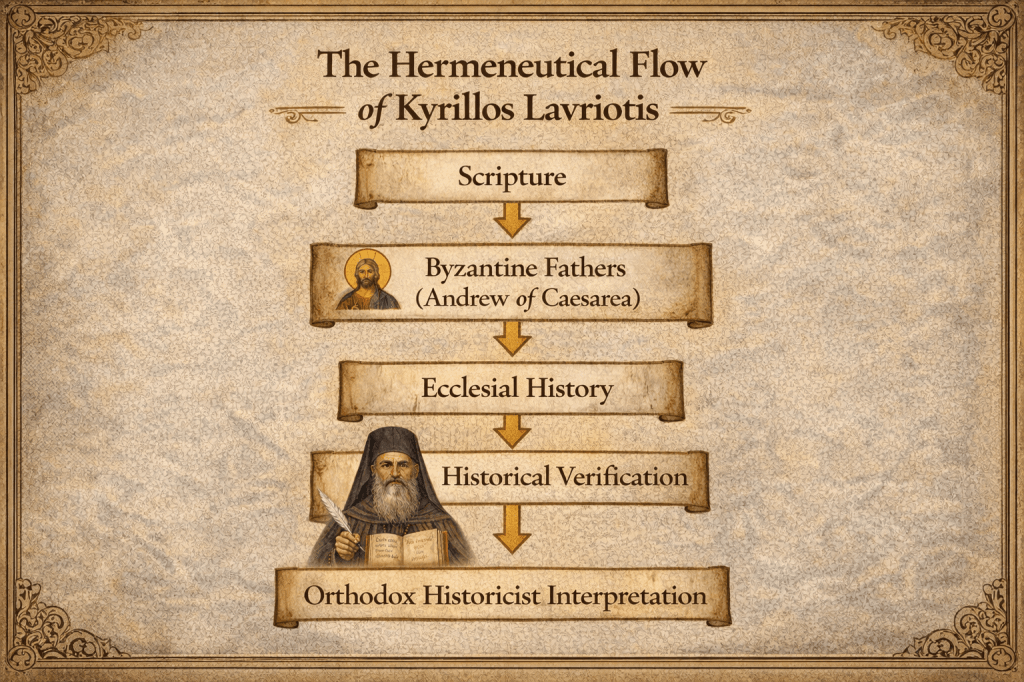

Lavriotis’s interpretive method stands squarely within the classical Orthodox approach exemplified by Andrew of Caesarea, while consciously resisting both allegorical abstraction and literalist reductionism. History, for Lavriotis, is neither a dispensational timetable nor a neutral backdrop; it is the arena of divine pedagogy, in which apocalyptic symbols unfold through real ecclesial and imperial events.

Central to this method is Lavriotis’s insistence on retrospective interpretation. Prophecy is not decoded in advance through private inspiration, but discerned through the unfolding of history itself. Apocalyptic meaning is confirmed by events, not imposed upon them. This epistemological posture allows Lavriotis to employ historical identifications and chronological reasoning while rejecting speculative futurism and date-fixation.¹

III. The Apocalypse as Ecclesiastical History

A defining feature of Lavriotis’s exegesis is his conviction that the Apocalypse is primarily a revelation of Church history, not a speculative forecast detached from doctrine. The seals, trumpets, and bowls correspond to successive historical epochs in the life of the Church, particularly its struggles over Christology, authority, and fidelity to apostolic tradition.

The Seven Churches of Asia are not treated merely as first-century communities, but as typological representations of real Orthodox ecclesial bodies across history. Revelation, for Lavriotis, unfolds within the lived experience of Orthodoxy rather than within abstract universality.²

IV.Retrospective Fulfillment and the Orthodox Historicist Method

A central and repeatedly stated principle in Kyrillos Lavriotis’s exegesis is that the prophecies of the Apocalypse can be understood only retrospectively, in light of their historical fulfillment. Although he fully acknowledges the intrinsic difficulty of the Book of Revelation, Lavriotis insists that it is nonetheless a genuinely prophetic book, through which God reveals what must occur in the life of the Church between the first and second Parousia of Christ. Revelation is therefore neither an opaque riddle nor a purely mystical allegory, but a divinely ordered disclosure of ecclesial history, culminating in the final resurrection, judgment, and future life.

For Lavriotis, the Apocalypse functions as a summary and recapitulation of the whole of Scripture, gathering together biblical prophecy into a single Christocentric and ecclesiological vision. Yet its meaning is not immediately accessible. God reveals the visions to the Apostle John in advance, but their concrete interpretation is intentionally withheld until the events themselves unfold in history. As Lavriotis explains, the truth of apocalyptic prophecy becomes known not through speculative foresight, but through time itself, which discloses the correspondence between symbol and event.

This conviction underlies Lavriotis’s explanation for the relative silence or reserve of the ancient Church Fathers regarding the Apocalypse. According to him, the doctors of the early Church did not refrain from commentary out of ignorance or fear, but out of epistemological humility. Since many of John’s visions were to be fulfilled far into the future, the Fathers recognized that they lacked the historical vantage point necessary to provide definitive interpretations of every symbol. Where they did comment, their explanations were necessarily partial, provisional, or symbolic rather than historically precise.

Lavriotis expresses this principle succinctly when he writes: “It is the unfolding of events, or else it is time, that will make us know the truth on this subject.” Apocalyptic interpretation, in his view, is governed by divine economy rather than human curiosity. History itself becomes the exegetical key. In articulating this approach, Lavriotis consciously situates himself within the patristic tradition, especially that of Andrew of Caesarea. Andrew’s well-known remark concerning the mark of the beast—“Time and experience will reveal to sober researchers the precision of the number and the other things written about it”—is not merely cited but effectively expanded into a comprehensive hermeneutical principle. What Andrew applied cautiously to a single symbol, Lavriotis applies systematically to the whole Apocalypse.

This retrospective principle explains several defining features of Lavriotis’s Orthodox historicism. It accounts for his reluctance to engage in precise date-setting, even when employing extended prophetic periods such as the 1260 years. It justifies his insistence that apocalyptic symbols must be tested against lived ecclesial experience rather than abstract systems. And it allows him to affirm both the prophetic certainty of Revelation and the provisional character of human interpretation. In this way, Lavriotis offers a distinctively Orthodox resolution to the tension between prophecy and history. Revelation is fully authoritative and genuinely predictive, yet its meaning unfolds within time, discerned gradually as God’s providential governance of the Church becomes manifest. Apocalyptic interpretation thus remains ecclesial, historical, and sober—guarded against both premature speculation and skeptical reduction.

V. The Seven Thunders and Conciliar Dogma

It is necessary to clarify Lavriotis’s position regarding the Seven Thunders of Revelation 10 in relation to the Seven Ecumenical Councils. Unlike Metropolitan John of Myra, who explicitly and systematically identified the Seven Thunders with the Seven Ecumenical Councils, Lavriotis does not formulate this identification in an explicit or enumerated manner.

Rather, Lavriotis treats the Seven Thunders as authoritative divine proclamations already fulfilled within the historical life of the Church. His focus falls not on decoding each thunder symbolically, but on the fact that their utterances are sealed and not written—an indication, in his view, that their doctrinal content has already been received, preserved, and safeguarded by the Orthodox Church. The silence imposed upon the Thunders thus signifies not absence, but completion: the Church already lives from these revealed truths and does not await their future disclosure.

In this sense, Lavriotis presupposes the conciliar finality of dogma without restating the symbolic schema later made explicit by John of Myra. His interpretation is therefore fully compatible with the conciliar reading of the Thunders, but it is implicit rather than systematic. This distinction is critical for accurately situating Lavriotis within the Orthodox historicist tradition and for recognizing John of Myra’s chronological and conceptual priority in articulating the councils–thunders identification.

Lavriotis’s treatment nonetheless reinforces a central Orthodox Historicist conviction: that the Apocalypse is inseparable from the dogmatic and conciliar history of the Church³, and that its most decisive revelations are already embedded within the conciliar and liturgical life of Orthodoxy, resisting any attempt to marginalize doctrine in apocalyptic interpretation.

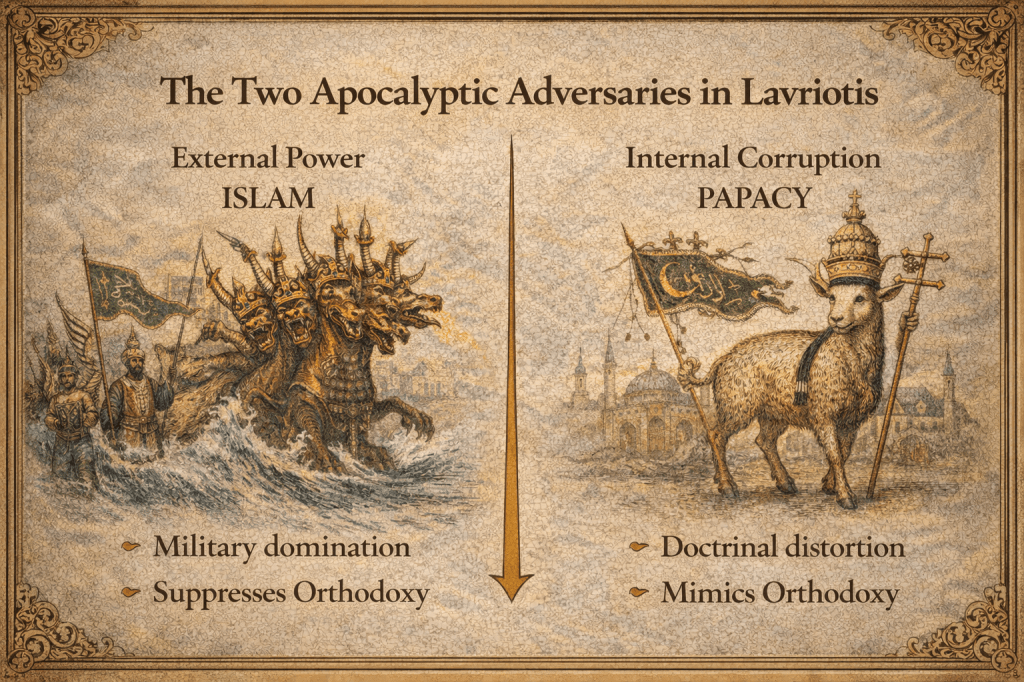

VI. Antichrist, Apostasy, and False Universality

Lavriotis rejects futurist conceptions of Antichrist as a single end-time tyrant. Antichrist is instead understood as a historical and ecclesial phenomenon—a system of false universality that mimics catholicity while undermining Orthodox dogma.

Within this framework, Lavriotis consistently identifies two principal antagonistic powers in Church history: Islam and the Papacy. These function as coordinated but distinct apocalyptic adversaries, corresponding to external domination and internal corruption respectively. This dual-enemy structure becomes a defining feature of later Orthodox historicist interpretation.⁴

VII. Chronology, the 1260-Year Period, and Orthodox Historicist Time

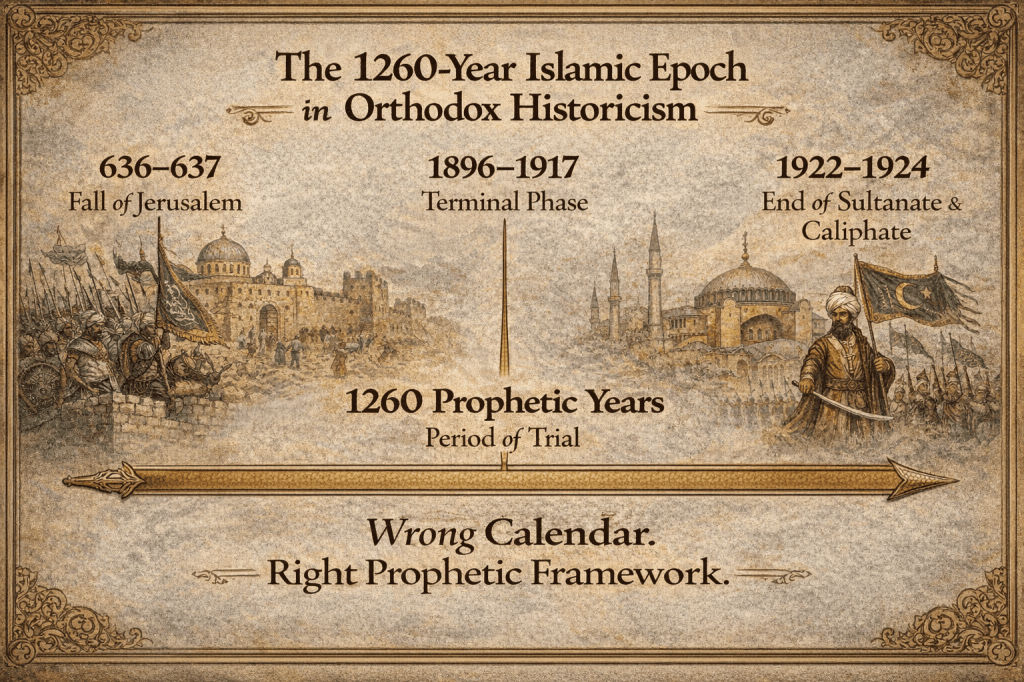

A crucial dimension of Lavriotis’s Neo-Historicist framework is his treatment of prophetic chronology, especially the recurring apocalyptic period of 1260 days, expressed in Revelation as 42 months and “time, times, and half a time.” Lavriotis explicitly treats these expressions as symbolically equivalent and interprets them according to the day–year principle, whereby prophetic days signify historical years.⁵

The 1260 years are not understood as a future three-and-a-half-year tribulation, but as a prolonged historical epoch characterized by ecclesiastical humiliation, Christological negation, and Orthodox endurance.

VII.1. Jerusalem, the Abomination of Desolation, and the Islamic Epoch

The chronological anchor of this framework is the Islamic conquest of Jerusalem (636–637), identified in Orthodox tradition as the realization of the Abomination of Desolation foretold in Daniel and referenced by Christ. This identification can be traced to Sophronius of Jerusalem, Patriarch of Jerusalem at the time of the conquest, who interpreted the fall of the Holy City as an eschatological rupture rather than a merely political defeat.⁶

Lavriotis inherits this interpretive horizon. The trampling of the holy city (Rev. 11:2), the prophecy of the Two Witnesses, and the Woman’s wilderness sojourn (Rev. 12) are read historically as coordinated descriptions of the Church’s condition under Islamic domination.⁷

VII.2. The 1260 Years as a Bounded Historical Duration

Lavriotis explicitly equates:

- 42 months × 30 days = 1260 days,

- 1260 prophetic days = 1260 historical years.

This period designates the duration of Islamic domination over Orthodox lands, during which the Church suffers restriction and humiliation without losing doctrinal integrity.⁸

VII.3. Explicit Calculations and Anticipated Decline

Lavriotis provides explicit chronological calculations, using traditional dates associated with the rise of Islam. Beginning from 585, he calculates:

- 585 + 1260 = 1845.

He also notes an alternative starting point of 576, yielding 1834. These calculations are offered as historically reasoned expectations, not as infallible predictions. Lavriotis further addresses Daniel’s 1290 years, explaining the thirty-year discrepancy theologically as a possible divine shortening of suffering.⁹

VII.4. Calendar Discrepancy and Historical Verification

From a modern perspective, these projected dates appear imprecise. Yet the discrepancy lies not in Lavriotis’s hermeneutical framework, but in the calendarial systems available to pre-modern writers. When recalculated according to solar years, the prophetic horizon aligns closely with historical reality.

Approximately 1260–1280 solar years after the fall of Jerusalem corresponds to the terminal phase of Islamic imperial dominance embodied in the Ottoman Empire: military defeat (1912–1918), abolition of the Sultanate (1922), and abolition of the Caliphate (1924). The wrong calendar was employed, but the right prophetic structure was discerned.

VII.5. Retrospective Chronology and Ecclesial Restraint

Lavriotis explicitly warns against obsessive date-setting, describing attempts to know exact times and seasons as folly.¹⁰ His chronology is therefore retrospective and ecclesial, not predictive in the modern sense. Prophetic numbers delineate the scope and limits of historical trials, not their precise expiration dates.

VIII. Conclusion

Cyril Lavriotis emerges as one of the most complete Orthodox historicist interpreters of the Apocalypse in the post-Byzantine period. His exegesis integrates conciliar theology, ecclesiology, prophetic time, and historical experience into a coherent framework governed by Orthodox restraint and historical realism. Far from borrowing from later Protestant historicism, Lavriotis stands within an internal Orthodox tradition that reads Revelation as the long, suffering, and ultimately vindicated history of the Church.

Lavriotis thus provides a crucial foundation for contemporary Greek Orthodox Historicism, demonstrating that historicist apocalyptic interpretation is neither foreign to Orthodoxy nor inherently speculative, but an authentically ecclesial mode of reading sacred history.

Footnotes

- Kyrillos Lavriotis, Commentary on Revelation, in Asterios Agyriou, Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse (1453–1821) (Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies), discussion of interpretive restraint.

- Ibid., commentary on Revelation 1–3.

- Ibid., commentary on Revelation 10.

- Ibid., commentary on Revelation 13.

- Ibid., commentary on Revelation 11–12.

- Sophronius of Jerusalem, Synodical Letter, as received in Orthodox historical tradition.

- Lavriotis, Les Exégèses, commentary on Revelation 11–12.

- Ibid., explicit identification of the 42 months with Islamic domination.

- Ibid., calculations using 576/585 and discussion of Daniel 12.

- Ibid., warning against precise date-fixation.

- On the use of monastic epithets indicating Athonite affiliation rather than strict enclosure, see Asterios Agyriou, Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse (1453–1821) (Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies), discussion of post-Byzantine exegetes and manuscript provenance.

All are consistent with providing true interpretations from the events of the prophecy. It is good article

LikeLiked by 1 person