Revelation, Allegory, and the Eagle’s Warning (Rev 8:13)

by Jonathan Photius, NEO-Historicism Research Project

Introduction

The reception history of the Apocalypse in the Christian East presents a paradox that has rarely been examined in a unified way. Although the Book of Revelation was eventually received as canonical, its historical function—as a prophetic disclosure of the life of the Church across time—was increasingly muted. The Apocalypse was preserved, revered, iconographically celebrated, and liturgically echoed, yet progressively detached from the concrete history of the Body of Christ as it unfolds within time.

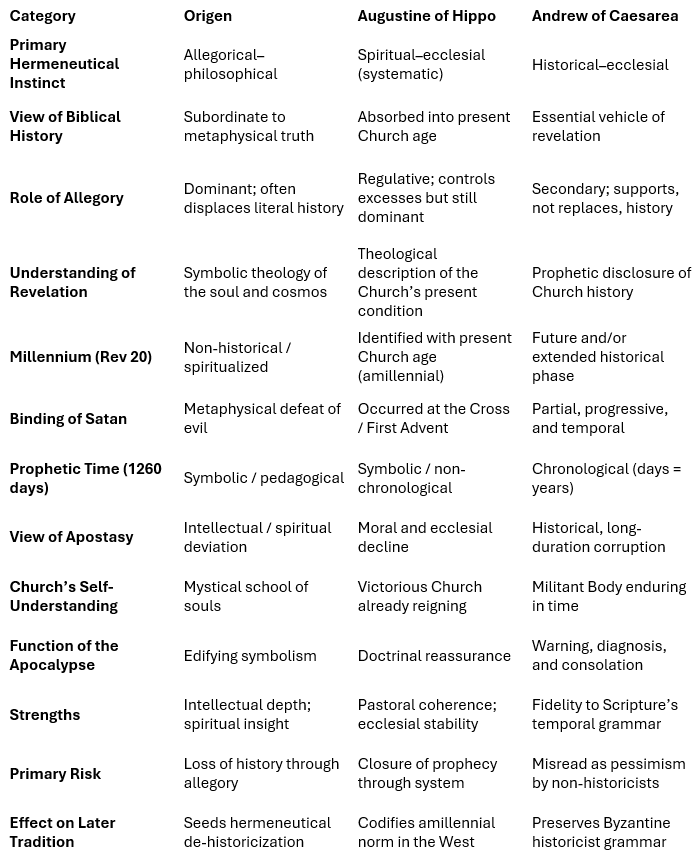

This article argues that this detachment arose not from a single doctrinal error, but from a hermeneutical trajectory beginning with the over-allegorization of Scripture associated with Origen, developing into amillennialism, and ultimately becoming systematized through Augustine of Hippo. Drawing upon Apostolos Makrakis’s historicist interpretation of Revelation—especially his identification of Origen with the Third Trumpet—this study proposes that the Apocalypse itself anticipates and warns against this loss of historical vision through the appearance of the Eagle in Revelation 8:13, traditionally associated with John the Evangelist.

I. Origen and the Reordering of Meaning

Origen stands as one of the most formidable intellects of the ante-Nicene Church. As an exegete and catechist, he functioned as a genuine luminary—precisely the kind of “star” Revelation associates with ecclesial leadership. Yet Origen’s enduring influence lies less in particular doctrinal positions than in a deeper reordering of meaning.

Origen did not deny the historical sense of Scripture outright, but he consistently subordinated it to spiritual, philosophical, and metaphysical interpretation. Biblical history increasingly functioned as symbolic scaffolding for eternal truths rather than as revelatory action unfolding in time. Salvation history thus became pedagogical rather than prophetic; narrative became illustrative rather than determinative.

It is this shift—not speculative doctrines as such—that Makrakis identifies as the poison of the Third Trumpet.

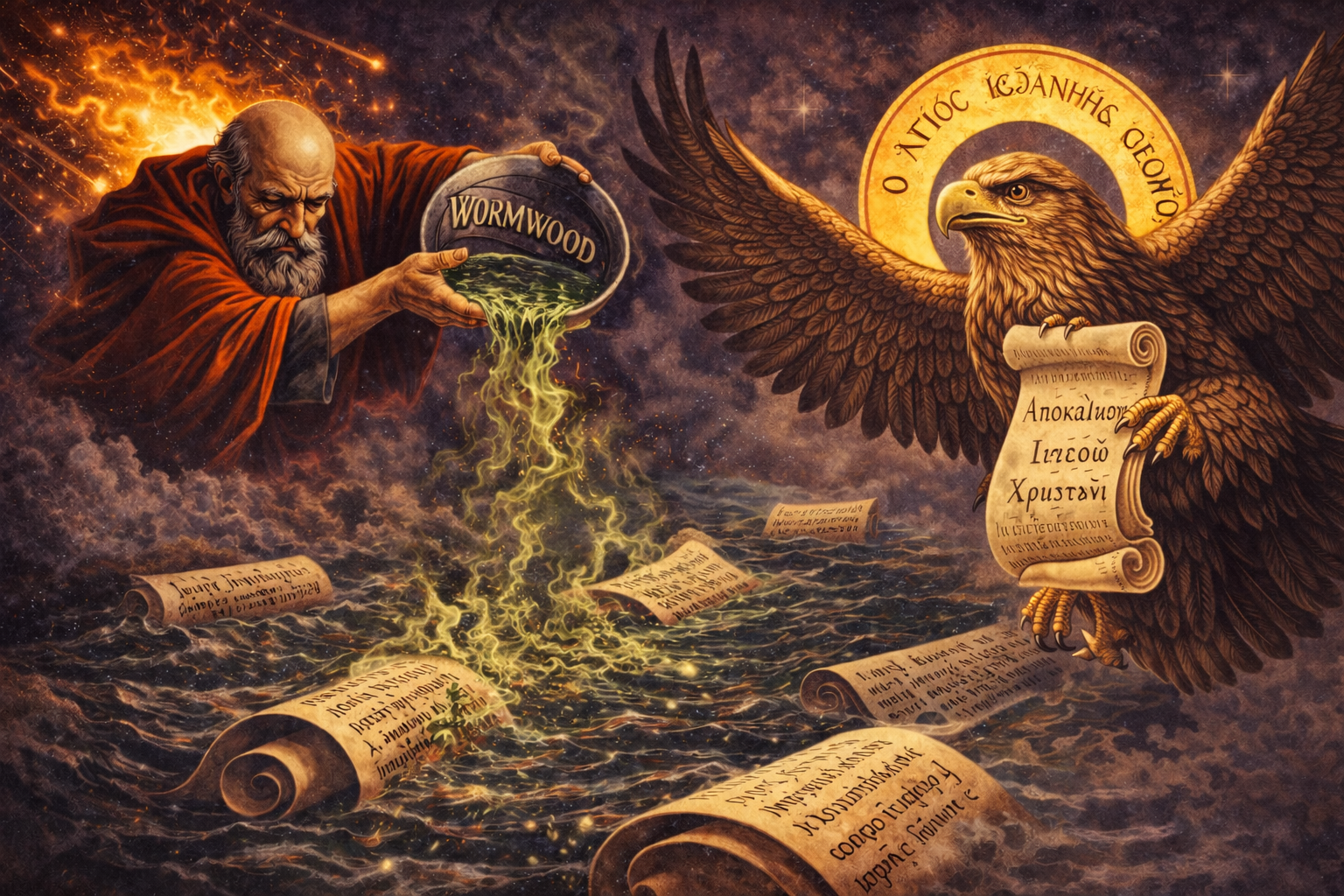

II. The Third Trumpet: Wormwood and the Poisoning of Interpretation

Revelation 8:10–11 describes a great star falling from heaven, called Wormwood, embittering the rivers and fountains of water. Makrakis interprets these images with striking concreteness: the rivers signify pastors and teachers, while the fountains signify Scripture itself. The fall of the star therefore represents an internal calamity—the corruption of interpretation rather than persecution from without.

Origen, once a brilliant beacon of the Church, fulfills this image with disturbing precision. His excessive reliance on Platonic metaphysics and allegorical method embittered the interpretive waters of Scripture, rendering prophecy elastic, ambiguous, and increasingly detached from historical fulfillment. The Apocalypse could still be read devotionally, but no longer functioned as a map of the Church’s future trials.¹

This embittering did not destroy doctrine outright. Rather, it undermined the Church’s capacity to read time.

III. From Allegory to Amillennialism

Amillennialism represents the natural maturation of this allegorical instinct. Once historical fulfillment is displaced by spiritual timelessness, the Millennium of Revelation 20 can no longer be read as a distinct phase in the life of the Church. Instead, it is absorbed into the present age, interpreted as the Church’s current spiritual reign.

Within this framework:

- the Kingdom is interiorized,

- prophetic sequence is collapsed,

- and endurance replaces expectation.

Revelation ceases to function as forward-looking prophecy and becomes instead a theological tableau describing the Church’s spiritual condition.

IV. Augustine and the Systematization of Timeless Fulfillment

Although Augustine explicitly rejected many of Origen’s speculative doctrines, Origen’s influence upon him must be understood at the level of hermeneutical inheritance rather than doctrinal agreement. By the late fourth and early fifth centuries, Origen’s allegorical approach—especially his suspicion of historical prophecy—had already reshaped the exegetical environment in which Augustine worked.

In De Civitate Dei, Augustine identifies the Millennium of Revelation 20 with the present age of the Church and places the binding of Satan at the Cross. This move is decisive. Once Satan’s binding is entirely relegated to the past, Revelation can no longer function as a prophetic disclosure of future ecclesial conflict. Long-duration apostasy becomes unintelligible, and prophetic time loses chronological meaning.²

From an Orthodox historicist perspective, Augustine’s synthesis represents a further stage in the eclipse initiated by Origen. What Origen undermined methodologically through allegory, Augustine stabilized doctrinally through amillennialism. The Apocalypse was not rejected—but it was rendered largely unnecessary as prophecy.

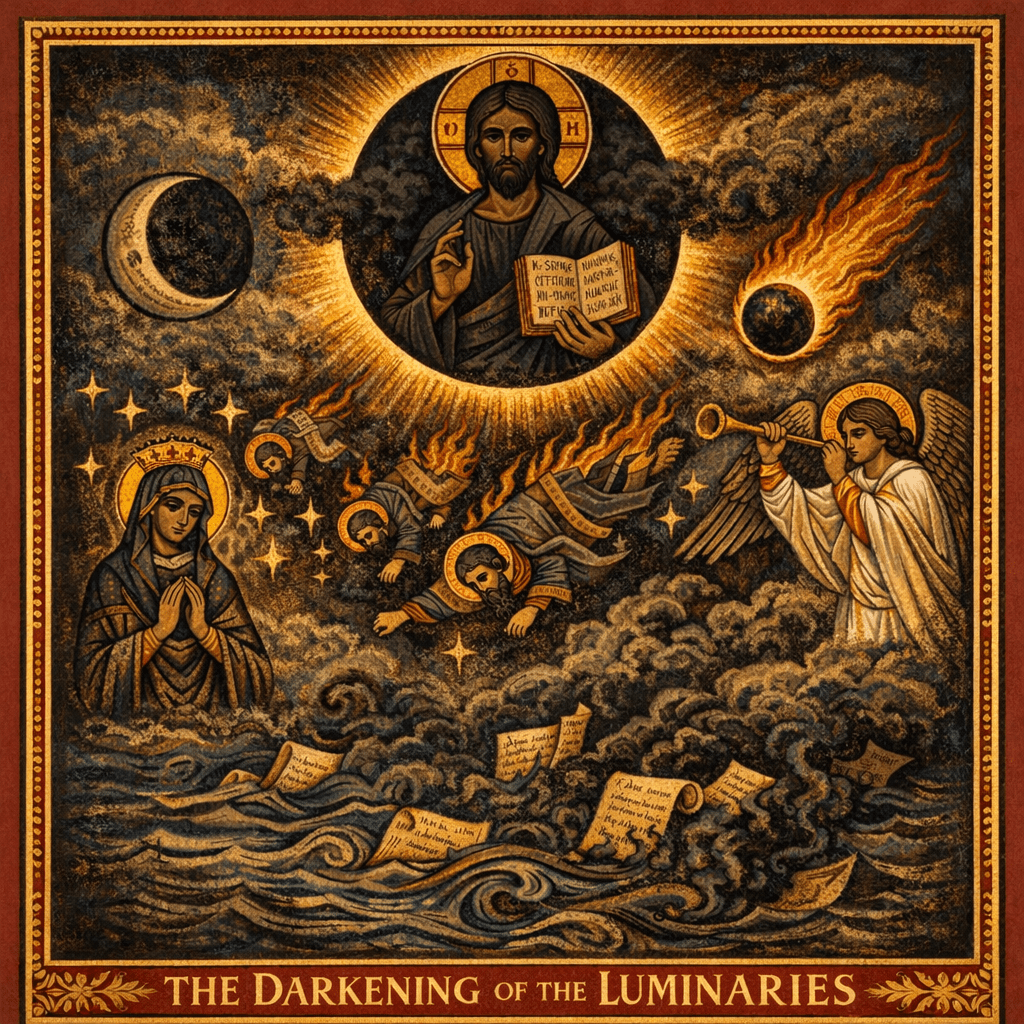

V. The Fourth Trumpet: The Darkening of Christological Vision

Makrakis’s interpretation of the Fourth Trumpet (Rev 8:12) follows directly from the Third. The darkening of one-third of the Sun does not signify any diminishment in Christ Himself, but rather a distortion in how Christ is known, taught, and applied within the Church. Christ ceases to function as the criterion of philosophy, history, and truth.

The Church (the Moon) continues to reflect light, but unevenly. Teachers (the Stars) continue to shine, but without a coherent historical framework. Holiness and sacrifice persist, yet the Church increasingly loses the ability to discern the meaning of her own trials.

The damage is not moral collapse, but historical blindness.

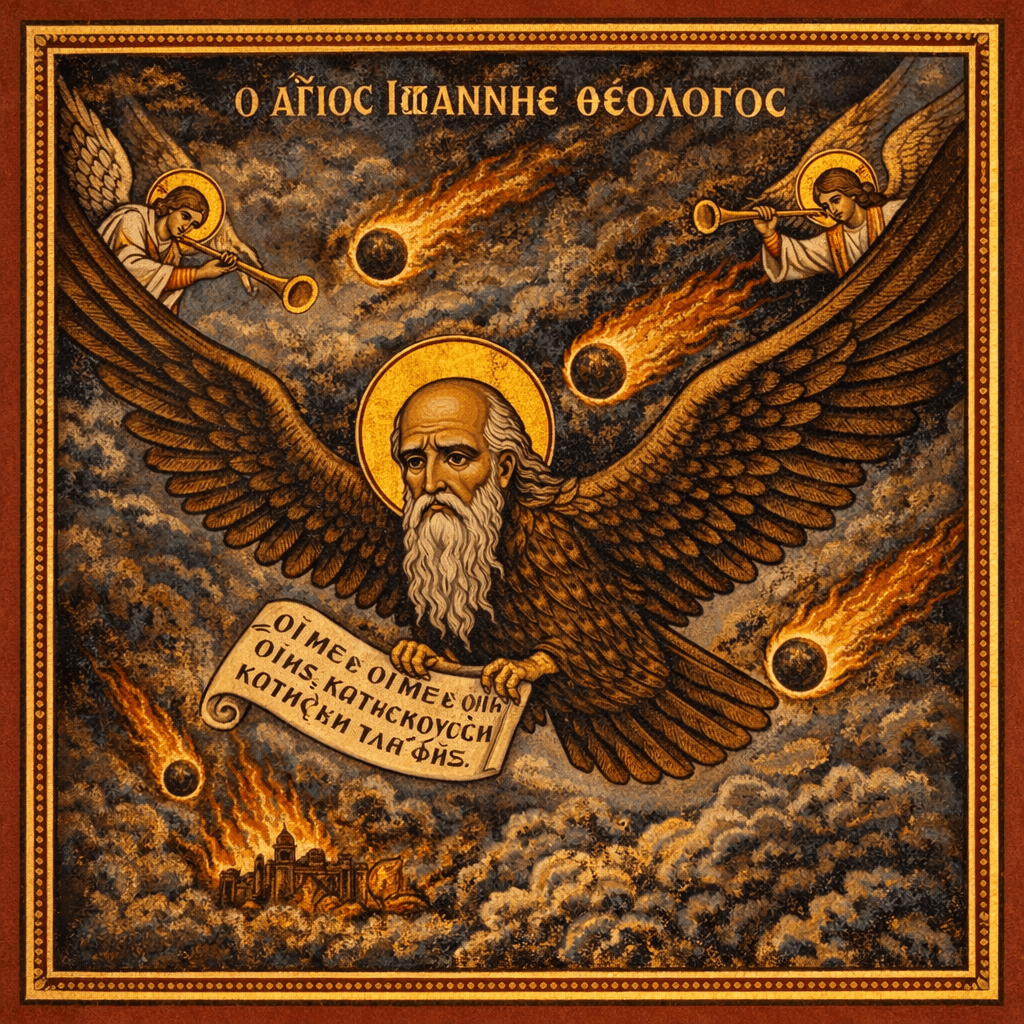

VI. The Eagle of Revelation 8:13 as Johannine Self-Correction

It is precisely at this point—after the darkening of ecclesial perception—that the Eagle appears:

“Woe, woe, woe to those who dwell on the earth…”

In Orthodox iconography, the Eagle is inseparable from John the Evangelist. Flying “in mid-heaven” signifies proclamation from within the Church itself, not from outside it. The warning is not addressed to pagans, but to the baptized—to those who possess the Apocalypse but no longer hear it as history.

The Eagle’s cry announces that the Church’s failure to read Revelation historically will have grave consequences. Without historical vision, the Church will not recognize apostasy as it unfolds, will not discern the duration of its trials, and will not understand the meaning of the seventh trumpet and its 1260 days.

VII. Revelation as the Defense of the Body of Christ in Time

At stake is nothing less than the nature of the Incarnation. If Christ’s Body is real, then it exists in time. If the Church is His Body, then her history must matter. Revelation is the book in which Christ defends His Body across centuries of conflict, endurance, judgment, and purification.

Origenist allegory, amillennial timelessness, and the total binding of Satan at the Cross converge in a single effect: the displacement of the Church’s historical body from the center of the Apocalypse. The Eagle warns that this displacement will leave the faithful vulnerable—not to persecution, but to blindness.

Conclusion

Origen’s legacy, as interpreted by Makrakis, is not merely a cautionary tale about allegory, but a diagnosis of a hermeneutical wound whose effects persisted for centuries. Augustine’s amillennial synthesis represents not a rupture from this trajectory, but its stabilization. Together, these developments explain why the Apocalypse could be canonized yet rendered largely mute as prophecy.

The Eagle of Revelation 8:13 thus stands as a perpetual Johannine warning: unless the Apocalypse is restored to its function as sacred history, the Church will remain unable to discern apostasy, duration, and the meaning of the final trumpet.

© 2026 by Jonathan Photius

Footnotes

- Apostolos Makrakis, Interpretation of the Book of Revelation (Athens, 1881; Eng. trans. Orthodox Christian Education Society, Chicago, 1948), 187–193.

- Augustine of Hippo, De Civitate Dei, Book XX, esp. chs. 7–9.

- Revelation 8:10–13; 20:1–6.

- Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion, on Origen as fountainhead of later heresies.

- Andrew of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse, passim; contrast with Augustine on Rev 20.

- Henri de Lubac, History and Spirit: The Understanding of Scripture According to Origen (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2007).

- Asterios A. Agyriou, Les Exégèses Grecques de l’Apocalypse à l’Époque Turque (Thessaloniki, 1988).