By Jonathan Photius – The NEO-Historicist Research Project

Introduction

The interpretation of Revelation 9 has long been contested across Christian traditions. Western historicists have commonly identified the Fifth Trumpet with the rise of Islam. Futurists project it into a coming literal demonic plague. Preterists typically confine it to the events of the first century, frequently associating its imagery with Roman military activity or the Jewish War. Yet within the Greek Orthodox historicist tradition, a markedly different reading appears: the Fifth Trumpet is fundamentally Christological.

In this reading—articulated with particular force by Apostolos Makrakis—the Fifth Trumpet unveils the Church’s first great internal doctrinal crisis: the Arian controversy and the approximately one-and-a-half-century period of ecclesial torment culminating in the dogmatic clarifications of the first four Ecumenical Councils. Revelation 9 thus becomes not a prophecy of foreign invasion nor merely a symbol of imperial violence, but an apocalyptic disclosure of doctrinal purification, conciliar warfare, and ascetical renewal.

This article presents a full analysis of that interpretation, integrating additional historical and theological observations: (1) the symbolic identification of fallen “stars” as ecclesiastical leaders; (2) the Christological significance of the darkened “Sun” and “Air”; (3) the year-day principle applied to the “five months” of torment; (4) the conciliar struggle as a form of apocalyptic “war in heaven”; and (5) the rise of monasticism as a paradoxical fulfillment of Revelation 9:6. The article concludes by situating this reading in contrast with preterist, futurist, and Western historicist interpretations.

I. The Fallen Star: Ecclesial Leadership in Apocalyptic Symbolism

Revelation 9 opens with the sounding of the fifth angel:

“And I saw a star fallen from heaven unto the earth, and to him was given the key of the pit of the abyss.” (Rev. 9:1)

The Apocalypse itself provides an interpretive key: in Revelation 1:20 the “stars” are identified as the angels of the churches—commonly understood in patristic exegesis as their ecclesial representatives or bishops.¹ Moreover, Old Testament precedent confirms celestial imagery for covenantal leadership. In Joseph’s dream (Gen. 37:9–10), stars represent patriarchal rulers within Israel. Apocalyptic symbolism thus naturally associates stars with covenantal or ecclesial authority.

Within this framework, the “fall” of a star does not primarily signify geopolitical collapse, but the doctrinal or moral fall of a Church teacher. Makrakis interprets the fallen star of the Fifth Trumpet as Arius, presbyter of Alexandria, whose theological deviation inaugurated one of the most destabilizing doctrinal crises in Christian history.²

This identification situates the Fifth Trumpet within the internal life of the Church. The woe is not first military, but doctrinal. It unfolds not primarily on battlefields, but in synods, pulpits, imperial courts, and catechetical disputes.

II. The Abyss, the Smoke, and the Darkening of the Sun and Air

The fallen star receives the “key of the abyss” and opens it, releasing smoke that darkens “the sun and the air” (Rev. 9:2). The abyss (ἄβυσσος) is elsewhere associated with demonic imprisonment. In Luke 8:31 the demons beg Christ not to send them into the abyss; in Revelation 20 Satan himself is bound and shut within it.

Makrakis interprets the abyss as the prison-house of demonic forces restrained by divine authority.³ The “key” signifies permission granted within the economy of divine justice. The smoke that ascends is delusion—intellectual and spiritual obscurity permitted as a chastening and testing of the Church.

Crucially, the darkened “Sun” and “Air” are not astronomical but metaphysical. The Sun signifies Christ—the “Sun of Righteousness” (Mal. 4:2)—whose divine light illumines the Church. The Air signifies the Holy Spirit, the medium through whom Christ’s light is breathed and communicated.

Arianism precisely attacks these two loci:

- It denies the co-eternal divinity of the Son, obscuring the Sun.

- It destabilizes the doctrine of the Spirit, obscuring the Air.

Athanasius describes Arian theology as striking at the very heart of salvation, for if the Son is not truly God, humanity remains unredeemed.⁴ The darkening is therefore soteriological, not cosmetic. The smoke obscures the identity of the Savior.

III. Torment Without Destruction: The Nature of the Arian Crisis

Revelation states that the locusts emerging from the smoke were not given power to kill, but to torment (Rev. 9:5). This distinction is decisive.

The Arian controversy did not annihilate the Church; it tormented her. The fourth century witnessed:

- Exiles of orthodox bishops (most famously Athanasius, exiled multiple times).⁵

- Imperial pressure in favor of Arian or semi-Arian formulas.⁶

- Social and ecclesial fragmentation.

- Theological confusion extending into marketplaces and households.

Socrates Scholasticus reports that theological debates were so widespread that even tradesmen engaged in disputes over the consubstantiality of the Son.⁷ Sozomen similarly describes the turbulence and factionalism that followed the Council of Nicaea.⁸ Gregory of Nyssa famously characterizes the atmosphere as a kind of frenzy.

This corresponds closely to the scorpion-like torment of Revelation 9: spiritual agony, not physical annihilation. The Church is wounded but not destroyed.

IV. The “Five Months”: The Year-Day Principle and the 150-Year Duration

The text specifies a duration:

“They were given that they should be tormented five months.” (Rev. 9:5)

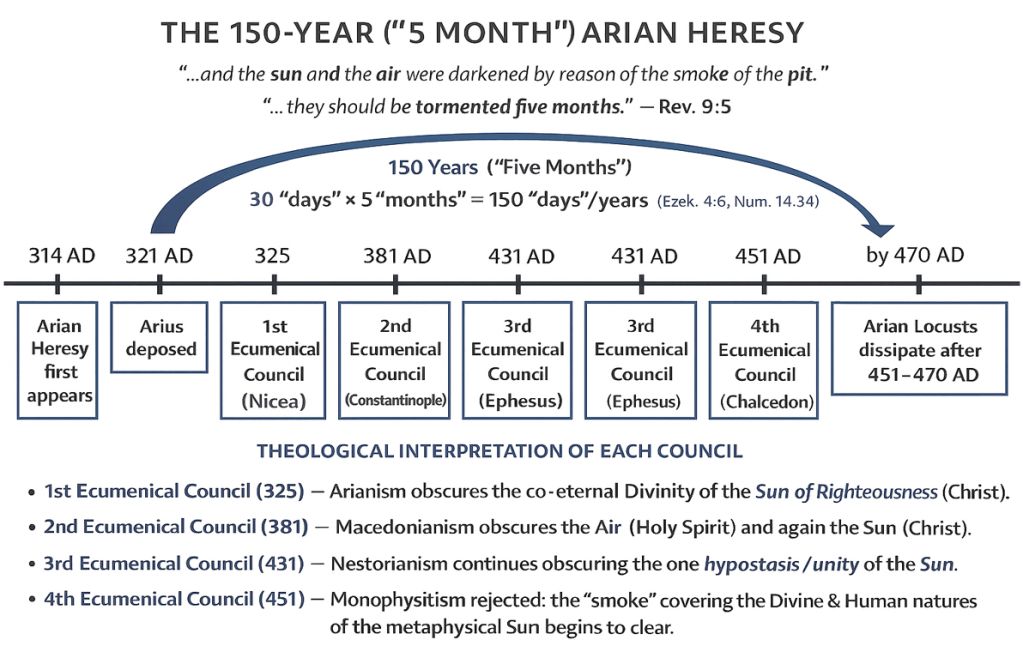

Makrakis applies the biblical punitive year-day principle (Num. 14:34; Ezek. 4:6), whereby symbolic days correspond to years in contexts of divine judgment. Five months equal 150 days; thus, 150 years.

Historically, the Arian controversy spans approximately one and a half centuries from its early fourth-century eruption through the doctrinal consolidation achieved by the first four Ecumenical Councils and their aftermath (325–451 and slightly beyond). The chronological arc may be summarized:

- Emergence of Arian teaching (c. 318–321)

- Council of Nicaea (325)

- Council of Constantinople (381)

- Council of Ephesus (431)

- Council of Chalcedon (451)

The period from Nicaea to Chalcedon alone encompasses 126 years, and when the earlier spread and later lingering effects are included, the approximate 150-year period becomes historically plausible within a historicist framework.

Unlike preterist compression or futurist projection, this interpretation takes the time statement seriously as a measured historical epoch.

V. Conciliar Warfare as Apocalyptic “War in Heaven”

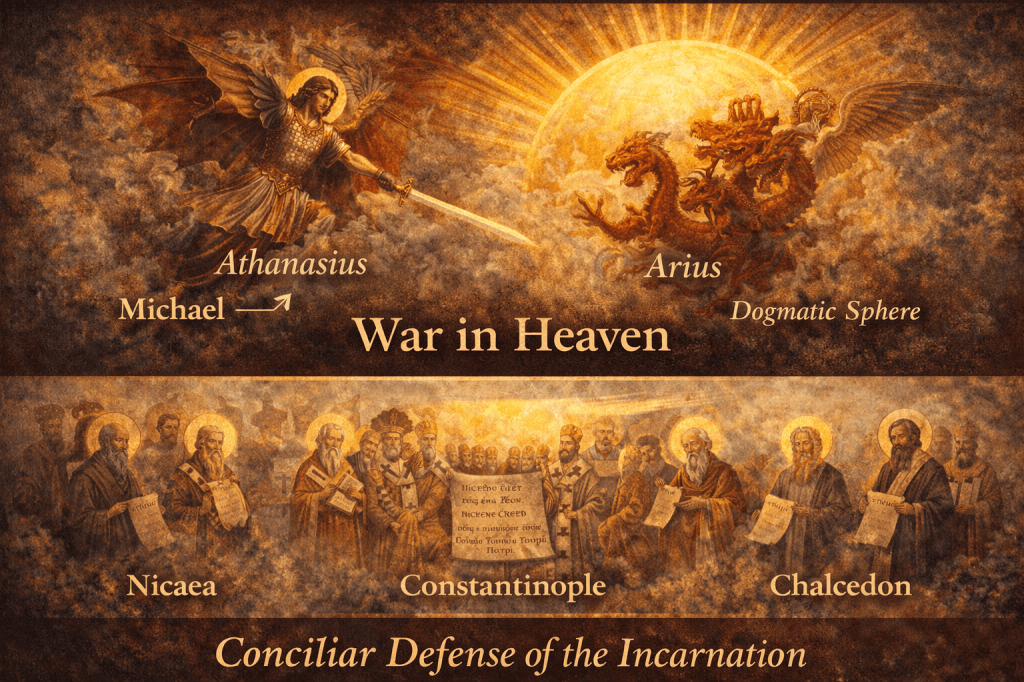

Revelation’s martial imagery—angels, casting down, warfare—need not be confined to literal combat. In the Arian age, the battlefield was dogmatic.

The first four Ecumenical Councils functioned as a coordinated counteroffensive:

- Nicaea (325) — Affirmed the Son as ὁμοούσιος with the Father.

- Constantinople (381) — Affirmed the divinity of the Holy Spirit.

- Ephesus (431) — Defended the unity of Christ’s person against Nestorian division.

- Chalcedon (451) — Clarified the two natures united without confusion.

Each council dispersed layers of theological “smoke.” The Sun and the Air gradually reemerged in doctrinal clarity. The Church’s warfare was not against flesh and blood, but against false teaching and the passions that gave rise to it.

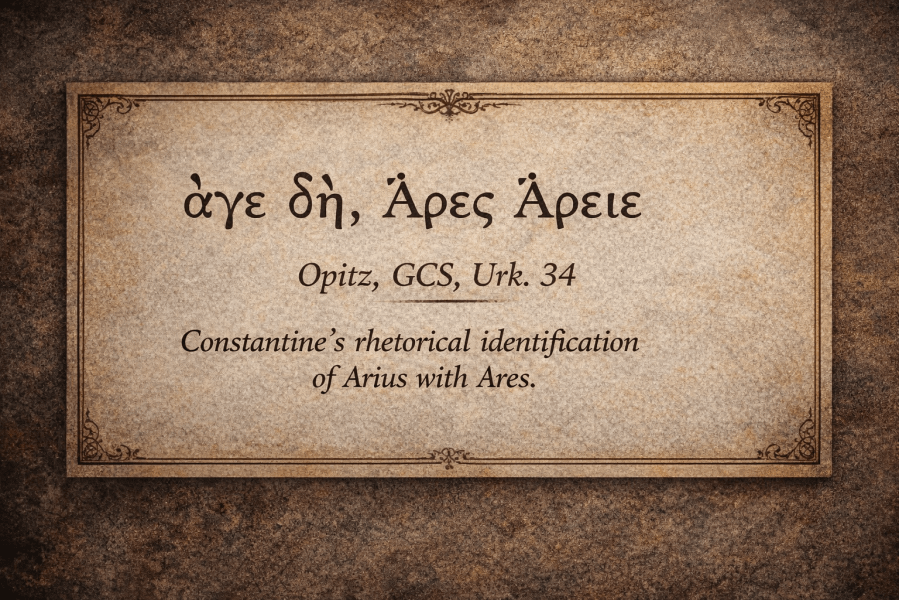

Constantine himself recognized the divisive character of Arius’ activity. In a letter preserved among the documentary corpus of the Arian controversy, he addresses Arius with a rhetorical pun: “ἄγε δή, Ἄρες Ἄρειε” (“Come now, Ares Arius”), associating him with the pagan god of war.⁹ The following section will explain in more detail.

VI. Abaddon, Apollyon, and the Historical Embodiment of the “Destroyer”

Revelation 9:11 names the king of the locusts:

“His name in Hebrew is Abaddon, and in Greek he is called Apollyon.”

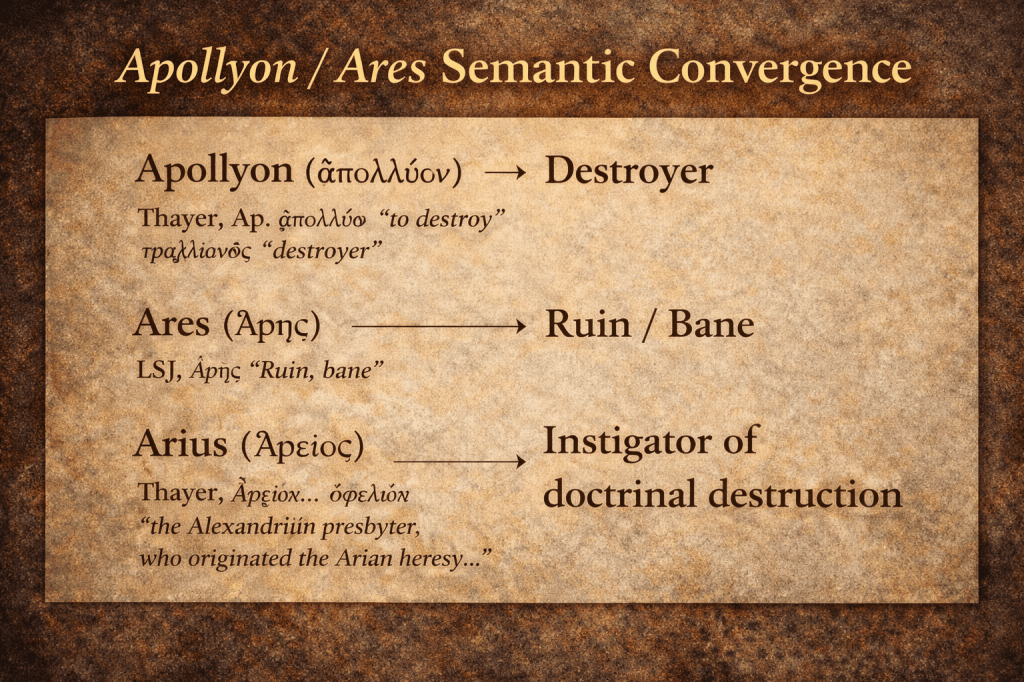

Both names signify “Destroyer.” The Greek verb ἀπολλύω means “to destroy utterly.”¹¹ The Apocalypse thus designates the demonic principle animating the locust army as destruction itself.

Within Makrakis’ interpretive framework, Apollyon represents the invisible demonic force loosed from the abyss, while Arius functions as the historical instrument through whom that destructive principle operates. The destroyer’s work is doctrinal devastation—the attempted destruction of the confession that Christ is fully God and fully man.

A striking historical detail reinforces this identification.

In a preserved Greek letter addressed to Arius during the height of the controversy, Emperor Constantine rebukes him with a pointed rhetorical pun:

ἄγε δή, Ἄρες Ἄρειε

(“Come now, Ares Arius…”)¹²

The Greek text is preserved in Hans-Georg Opitz’s critical edition of the Arian documents (Athanasii Werke III/1, Urkunde 34). This rhetorical identification underscores Arius’ role as an instigator of ecclesial warfare.

The play on words is unmistakable. Arius (Ἄρειος, Areios) is addressed as Ἄρης (Ares), the Greek god of war. Constantine thus associates Arius with conflict, agitation, and destructive strife within the Church.

By invoking Ares — the Greek god of war — Constantine casts Arius as the instigator of ecclesial conflict. The pun does not merely insult; it identifies Arius with the spirit of strife and destruction that had engulfed the Church.

The irony is profound.

Revelation 12 speaks of “war in heaven.” Constantine calls Arius “Ares.”

In Greek mythology, Ares embodies violent disruption and ruin. In the fourth century, Arius becomes the catalyst for doctrinal warfare within the Church. Thus, the historical Arius—whom Constantine rhetorically equates with the god of war—stands at the center of the conciliar “war in heaven” that raged across the fourth and fifth centuries.

The Apocalypse portrays a dragon cast down through heavenly conflict. In historical reality, the “war” against Arianism was waged through creeds, exiles, pastoral letters, and ascetic endurance. The councils functioned as the Church’s Michaelic counterstroke: the defense of the Incarnate Son against a doctrine that sought to reduce Him to creaturehood.

This parallel must not be pressed into allegorical excess. Revelation does not depend upon Greek mythology. Yet it is historically remarkable that the very teacher whose doctrine precipitated the Church’s great doctrinal war was publicly likened by the emperor himself to Ares, the archetype of war. The rhetorical convergence underscores what Revelation describes symbolically: a destructive principle unleashed, resisted, and ultimately cast down through divine providence.

The semantic field surrounding the name Ares is significant. In classical Greek usage, the noun ἄρη can denote “bane,” “ruin,” or destructive calamity.¹³ Ares is not merely the god of combat, but the embodiment of violent devastation and chaos. Constantine’s wordplay therefore situates Arius rhetorically within a linguistic orbit of destruction and ruin.

This correspondence is not mythological speculation but historical rhetoric. Arius’ teaching fractured episcopal unity, destabilized liturgical confession, and provoked imperial intervention. Socrates Scholasticus records the widespread agitation caused by the controversy, noting that debates over doctrine permeated civic life.¹⁴ Sozomen similarly recounts the divisions that spread throughout the empire.¹⁵

The Apocalypse’s title “Apollyon”—Destroyer—thus finds a historically intelligible embodiment in the Arian crisis. The parallel rests not on phonetic coincidence but on shared theological meaning:

- Abaddon / Apollyon = Destroyer

- Ares = ruin, devastation

- Arius = instigator of ecclesial warfare and doctrinal destruction

Athanasius argues repeatedly that if the Son is not truly God, humanity remains unredeemed.¹⁶ In this sense, Arianism is destructive at the level of salvation itself. It does not merely introduce intellectual confusion; it threatens the very possibility of deification and redemption.

Therefore, when Revelation describes a demonic “Destroyer” leading a tormenting host during a measured historical period, and when the fourth century witnesses a Church teacher whose doctrine nearly dismantled Nicene confession, the convergence becomes theologically compelling.

Importantly, this identification does not require declaring Arius an eschatological Antichrist figure. Rather, he is understood typologically as the historical vehicle through whom the destructive principle described in Revelation 9 operated within the Church. The invisible destroyer works through visible instruments. The demonic war in heaven is manifested in conciliar struggle on earth.

VII. “Seeking Death” and finding Eternal life: Monasticism as the Ascetical Counter-Movement

Revelation 9:6 declares:

“In those days men shall seek death, and shall not find it.”

Makrakis interprets the torment of the Fifth Trumpet as the psychological and ecclesial distress generated by the Arian controversy. Yet the fourth century also witnessed a parallel and providential development: the rise of monasticism in Egypt with the Desert Fathers. Following Constantine, the Church entered an era of imperial favor in which prestige, political influence, and episcopal ambition introduced new spiritual dangers. In this context, the ascetical movement may be read typologically through Revelation 12: as the Woman “fled into the wilderness,” so too the faithful enacted a renewed flight into the Egyptian desert. This was not a rejection of the Church, but a preservation of her inner life. As the imperial Church contended publicly with Arianism in councils and courts, the desert became a sphere of purification, intercession, and doctrinal fidelity.

This ascetical withdrawal also casts light upon one of the most enigmatic statements of the Fifth Trumpet: “In those days men will seek death and will not find it; they will long to die, and death will flee from them” (Rev. 9:6). Makrakis reads this as the inner anguish produced by doctrinal confusion. Yet within the same historical horizon, a paradox emerges. The age of martyrdom had largely ceased, but a new form of voluntary death arose. Monastic tonsure was understood as burial to the world—an enacted renunciation of ambition, possession, and status. Those who “sought death” in ascetical self-denial did not find annihilation; rather, death fled from them, for in losing their life they found it (Matt. 16:25). The torment that destabilized many became, for others, the occasion of purification.

Athanasius’ Life of Antony depicts the monastic vocation as a living martyrdom—death to the world in imitation of Christ.¹⁶ Basil the Great organized cenobitic communities rooted in ascetical discipline and doctrinal fidelity.

Here Revelation’s paradox becomes luminous:

They seek death—but death flees from them.

The monks voluntarily embrace “white martyrdom.” Having crucified the old man, they are less susceptible to the locust sting of heresy. The ascetical movement becomes a providential strengthening of the Church precisely during the Fifth Trumpet’s torment.

VIII. Comparison with Preterist and Other Interpretations

Preterist readings typically confine the Fifth Trumpet to first-century events, often associating locust imagery with Roman armies or Jewish revolt symbolism. Yet such interpretations struggle to account for:

- The explicitly ecclesial symbolism of fallen stars.

- The Christological darkening of Sun and Air.

- The measured duration of five months.

- The internal, doctrinal character of the torment.

Futurist readings literalize the imagery into a future demonic plague but disconnect it from identifiable historical epochs. Western historicist readings frequently equate the locusts with Islamic forces; however, Islam primarily represents an external geopolitical phenomenon, whereas Arianism represents an internal Christological crisis striking at the heart of Christian confession.

The Orthodox historicist interpretation preserves the text’s ecclesial focus, theological depth, and historical specificity.

Conclusion

The Fifth Trumpet, read through an Orthodox Ecclesial Historicist lens, is not a prophecy exhausted in the siege of Jerusalem nor a vision of distant futurist catastrophe. It unveils the Church’s first great Christological woe: a measured period in which the confession of the Son was obscured, contested, and purified. The fallen star signifies the rise of doctrinal distortion; the smoke darkens the Sun and the Air—the revelation of the Son Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit; the locusts torment the ecclesial body; and the five months mark a defined and measurable epoch of theological crisis. The councils wage war in heaven. The desert becomes refuge.

Yet the Apocalypse does not culminate in darkness. Through conciliar warfare, ascetical preservation, and doctrinal clarification, the Church emerges with greater precision in her confession: the Son is ὁμοούσιος with the Father, Light from Light, true God from true God. The very crisis that threatened destruction becomes the instrument of dogmatic refinement.

In this light, the Fifth Trumpet reveals the pattern of divine providence in history. Heresy is permitted, not to annihilate the Church, but to compel her to speak more clearly of Christ. The woe becomes purification for the Sun-clothed Woman. The torment yields clarity for the Creed. The smoke lifts, and the Sun shines with greater brilliance.

Thus the Fifth Trumpet stands not as a mere episode of judgment, but as a testimony to the indestructibility of the Incarnation. The Destroyer does not prevail. The Church’s confession endures. And the Christ who was obscured in controversy is proclaimed with even greater precision through the councils of His Body.

© 2026 by Jonathan Photius

Footnotes

- See Rev. 1:20; cf. Andrew of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse, PG 106.

- Apostolos Makrakis, Interpretation of the Book of Revelation (Athens, 19th c.), on Rev. 9.

- Ibid.

- Athanasius, Orations Against the Arians I.9–10, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 2nd series, vol. 4.

- Socrates Scholasticus, Ecclesiastical History II–IV.

- Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History II–VI.

- Socrates, Ecclesiastical History V.

- Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History III.

- Hans-Georg Opitz, ed., Athanasii Werke, III/1: Urkunden zur Geschichte des arianischen Streites (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1934), Urkunde 34.

- Liddell-Scott-Jones, Greek-English Lexicon, s.v. “ἀπολλύω.”

- Hans-Georg Opitz, ed., Athanasii Werke, vol. III/1: Urkunden zur Geschichte des arianischen Streites 318–328 (GCS Neue Folge 3; Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1934), Urk. 34.

- Liddell-Scott-Jones, Greek-English Lexicon, s.v. “ἄρη.”

- Socrates Scholasticus, Ecclesiastical History, II–V.

- Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History, II–VI.

- Athanasius, Orations Against the Arians, I.9–10, NPNF 2nd series, vol. 4.

- Athanasius, Life of Antony, trans. Robert C. Gregg (New York: Paulist Press, 1980).

Good article Sir Jonathan

On Wed, Feb 11, 2026, 9:59 PM NEO-Historicism – End Times Eschatology From

LikeLiked by 1 person