By Jonathan Photius – The NEO-Historicism Research Project

Introduction: Revelation 11 as Ecclesial History

Revelation 11 is not an isolated apocalyptic tableau but a deliberate recapitulation of Daniel 7, transposed into the lived experience of the Church. The Apocalypse preserves Daniel’s structure—testimony, opposition, judgment, silencing, and vindication—but renders it ecclesially, not geopolitically.¹ The prophetic drama unfolds not in abstraction, but within the historical life of the Church, her councils, her captivity, and her public humiliation.

Four elements dominate the chapter:

(1) a defined prophetic period of 1,260 days,

(2) the Two Witnesses,

(3) the Great City, and

(4) the πλατεῖα, the public square where the witnesses lie exposed.

Read through the Orthodox historicist tradition—most explicitly articulated by Cyril (Kyrillos) Lavriotis of Patras and Apostolos Makrakis—these elements converge on a single historical locus: Constantinople, the Queen of Cities, and its Sophianic heart, Hagia Sophia.²

I. Prophetic Time: Daniel 7 and the 1,260-Year Testimony

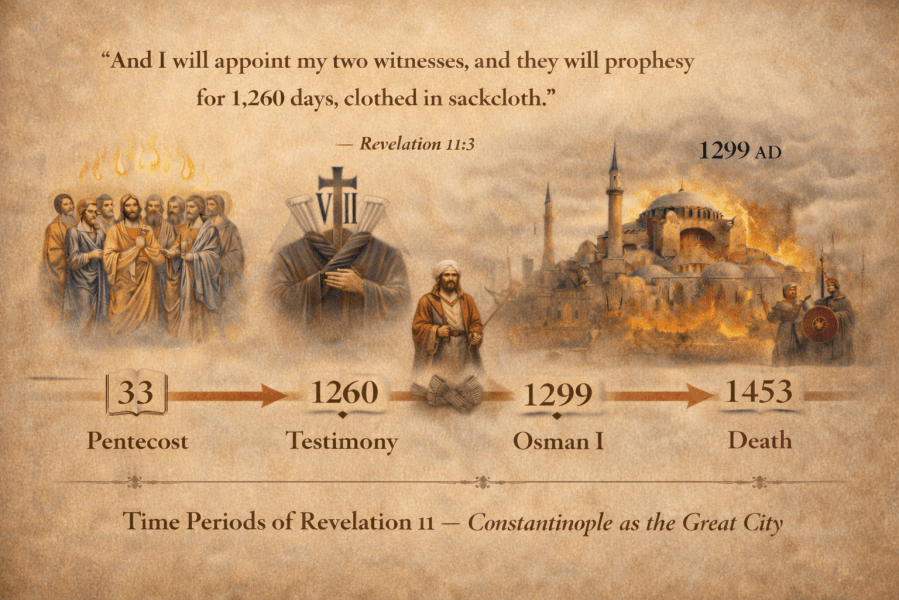

Revelation 11 equates the testimony of the Two Witnesses (1,260 days) with Daniel’s “time, times, and half a time” (Dan 7:25; 12:7). This correspondence is not incidental but exegetically decisive, signaling that Revelation 11 is intentionally Danielic in structure and scope.³

Within Orthodox historicist interpretation, this period is consistently understood according to the day–year principle, already sanctioned by Scripture itself (Num 14:34; Ezek 4:6). Cyril Lavriotis states unambiguously that the 1,260 days represent 1,260 years—a prolonged epoch of ecclesial testimony under persecution, not a brief future crisis.⁴ Apostolos Makrakis likewise interprets the forty-two months as twelve hundred and sixty solar years unfolding during the historical period of Christian empire and its subsequent humiliation.⁵

Equally important is the sequence of Revelation 11:

“When they shall have finished their testimony, the beast that ascendeth out of the abyss shall make war against them” (Rev 11:7).

The Beast does not interrupt the testimony; it arises after the testimony is complete. This permits, and indeed encourages, an ecclesial starting point at Pentecost, when the Church first receives the Spirit and begins public witness (Acts 2). From Pentecost (c. AD 33), a span of approximately 1,260 years reaches the late thirteenth century, coinciding with the emergence of Ottoman power as a distinct polity (c. 1290–1299). The decisive public silencing of that witness culminates in 1453, when Constantinople falls and the Church’s conciliar voice is crucified in history.⁶

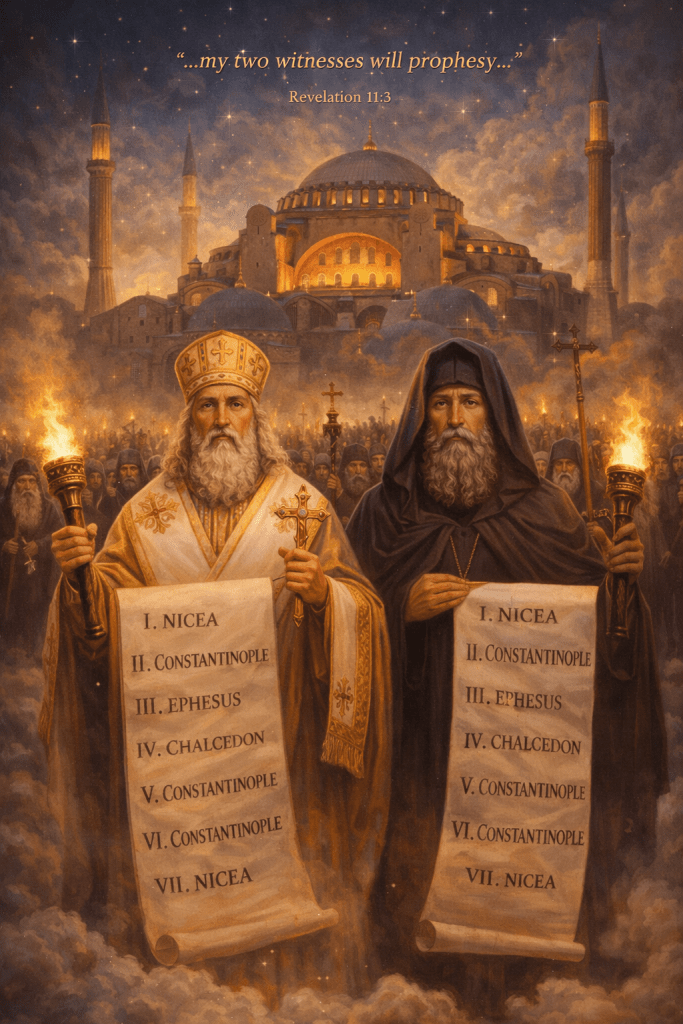

II. The Two Witnesses: Clergy and Laity, Council and Ascetic

Both Makrakis and Lavriotis explicitly reject the identification of the Two Witnesses as two individual prophets such as Elijah and Enoch. Instead, they interpret the Witnesses corporately and ecclesiologically.

Lavriotis identifies the Two Witnesses as the totality of Orthodox testimony: clergy and laity, spiritual and temporal authority, bishops, monks, confessors, emperors, and faithful.⁷ Their witness is doctrinal and ascetical, juridical and prophetic. Makrakis concurs, emphasizing that the Witnesses are those who worship at the altar (Rev 11:1), preserved even when the outer court is given to the nations.⁸

Clothed in sackcloth, the Witnesses signify repentance, suffering, and fidelity rather than triumphalism. The “fire proceeding from their mouth” (Rev 11:5) is therefore not violence, but dogmatic judgment: the conciliar condemnation of heresy and the prophetic exposure of false authority.⁹

III. Conciliar Testimony and the Great City

If the Two Witnesses represent the Church’s corporate testimony, that testimony must have a public, judicial locus. Revelation 11 names it: the Great City.

Makrakis states explicitly:

*“By the great city is here meant Constantinople.”*¹⁰

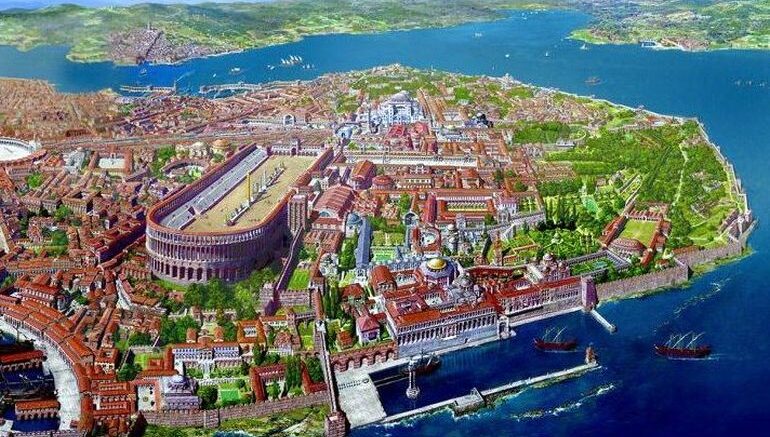

Constantinople was widely known in both common and literary usage as the Megalopolis—the “Great City”—a title reflecting not metaphor alone but lived historical reality. Rebuilt and magnified by Emperor Constantine, the city expanded rapidly through monumental construction, becoming one of the largest and most influential urban centers of the Mediterranean world. For over a millennium it served as the imperial capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, the seat of political authority, economic power, and Orthodox Christian life. Its unparalleled wealth, strategic position, and cultural gravity earned it enduring honorifics such as Basileuousa (“Queen of Cities”) and simply ἡ Πόλις (“the City”), names that testified to its singular status as the heart of empire and Church alike. In this sense, Constantinople’s identification as the “Great City” of Revelation is not symbolic inflation, but a historically grounded recognition of its unique role in shaping the Christian world.

This identification of “Great City” is historically precise. Constantinople functioned as the ecclesial tribunal of Christendom, the place where Christological truth was judged before the world through the Ecumenical Councils.

Councils held in Constantinople:

- Second Ecumenical Council (381)

- Fifth Ecumenical Council (553)

- Sixth Ecumenical Council (680–681)

- Seventh Ecumenical Council (787, initially convened there)

Councils within Constantinople’s immediate conciliar orbit:

- First Ecumenical Council (325), Nicaea (~55 miles away)

- Fourth Ecumenical Council (451), Chalcedon (across the Bosporus)

- Seventh Ecumenical Council (787), started in Constantinople and reconvened at Nicaea

With the partial exception of Nicaea (325), every Ecumenical Council was held in Constantinople or within its immediate imperial and ecclesial sphere, forming a single conciliar world in late antique and Byzantine reality.¹¹

IV. Egypt and Sodom: Captivity and Desecration

Revelation 11 states that the Great City is “spiritually called Egypt and Sodom.” Makrakis applies both designations directly to Constantinople.¹²

In Scripture, Egypt signifies the prolonged bondage of God’s covenant people. After 1453, the Orthodox Church entered a long captivity under Ottoman rule. Though faith survived, public sovereignty was lost. The parallel is striking: Israel’s bondage in Egypt (~400 years) and Greek Orthodox captivity under Ottoman domination (~400+ years).¹³

Sodom, by contrast, signifies not captivity but the inversion and desecration of what is holy. Under Ottoman occupation, Christian holy space was not merely suppressed but overturned: churches were stripped, silenced, and converted, their sacramental life extinguished or subordinated. At the same time, the Christian body itself became a site of violation. Through practices such as the devşirme system, Greek Christian boys were forcibly taken from their families, stripped of their faith and identity, and refashioned into Janissaries in service of the empire, while women and children were routinely enslaved and absorbed into imperial households. This systematic seizure and repurposing of Christian life—body, family, and worship—constituted a profound moral and spiritual desecration. In this sense, Constantinople after 1453 was not only an Egypt of prolonged bondage, but also Sodom: a place where holy things were inverted, the Church’s sanctity was publicly violated, and the natural order of Christian life was deliberately overturned.¹⁴

V. The πλατεῖα of the Great City: Hagia Sophia, Wisdom, and Conciliar Witness

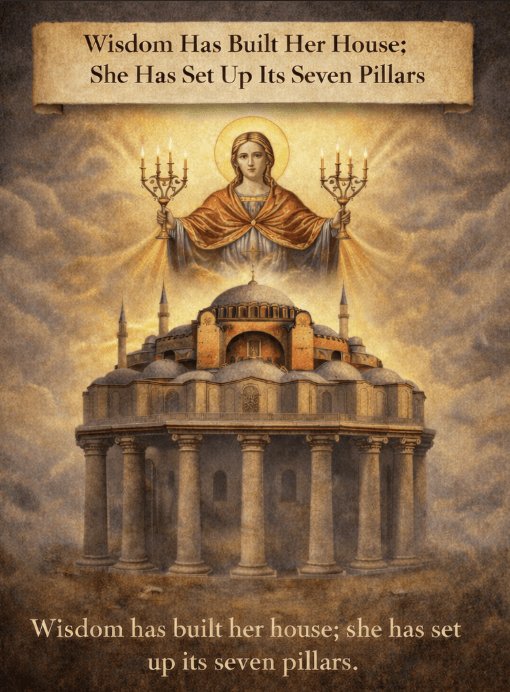

“Wisdom has built her house; she has set up its seven pillars.” (Proverbs 9:1)

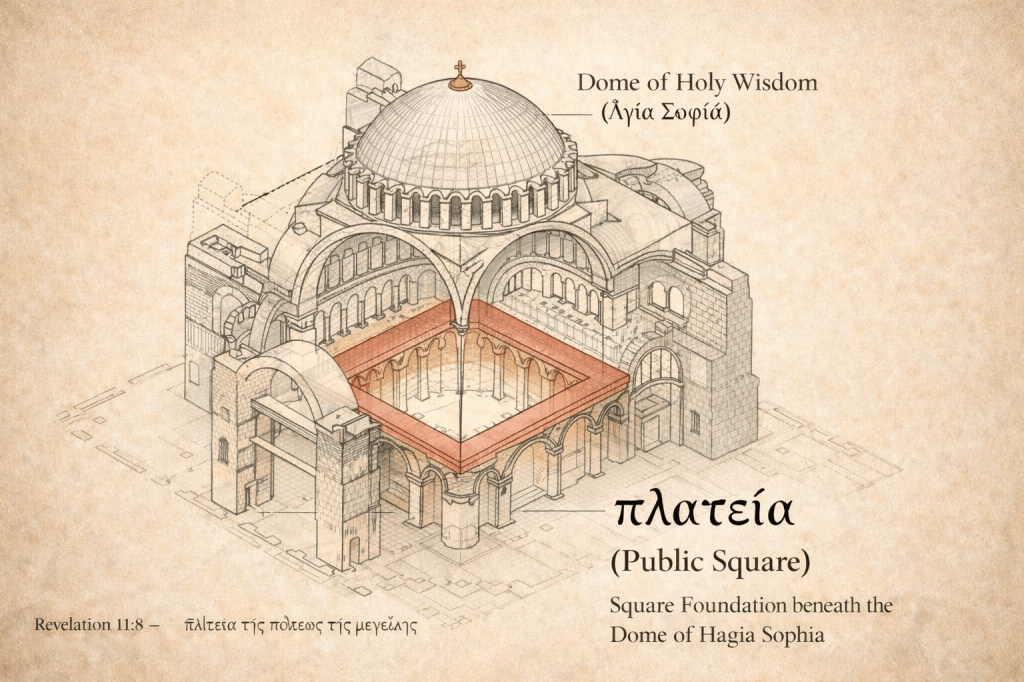

V.1 πλατεῖα and Public Exposure in Revelation 11

Revelation 11:8 locates the dead bodies of the Two Witnesses ἐπὶ τῆς πλατείας τῆς πόλεως τῆς μεγάλης—“upon the πλατεῖα of the Great City.” The term πλατεῖα does not denote a narrow street or incidental roadway, but a broad, open public space: a civic square, forum, or place of assembly where events are visible, judicial, and communal. Both classical and Koine usage consistently associate πλατεῖα with exposure before the polis rather than private concealment.¹⁵ The imagery therefore emphasizes not burial or disappearance, but public humiliation, silencing, and display before the nations.

Within Orthodox historicist interpretation, this lexical precision is decisive. The Two Witnesses are not removed from history, nor annihilated in secret; rather, their apparent defeat occurs in full view of the world. Apostolos Makrakis accordingly identifies the πλατεῖα as the central public space of the “Great City” itself, insisting that the Apocalypse speaks not of an abstract locale but of a concrete ecclesial and historical setting.¹⁶ The πλατεῖα is thus the stage upon which ecclesial testimony is judged, rejected, and exposed—yet not erased.

V.2 Hagia Sophia and the Square Architecture of the Great City

When the Great City is identified with Constantinople—a reading widely attested in post-Byzantine Greek exegesis—the architectural reality of Hagia Sophia assumes theological significance.¹⁷ The Great Church of Holy Wisdom is constructed not upon a basilical axis alone, but upon a clearly defined square bay, formed by four massive piers and unified through the pendentive system. Upon this square rests the great dome, making the square foundation both structurally and visually central.¹⁸

Architecturally, this square is not marginal or hidden; it is the most exposed and determinative space of the building. It gathers the assembly, supports the dome, and renders the interior a single unified public volume. In this sense, Hagia Sophia embodies in stone what Revelation 11 depicts symbolically: a public ecclesial space where witness is rendered visible, where judgment occurs, and where apparent defeat is displayed before rulers and nations. The πλατεῖα of the Great City is therefore not merely metaphorical; it corresponds strikingly to the square foundation beneath the dome of Holy Wisdom, the most public and theologically charged space of Constantinople.¹⁹

V.3 Wisdom Has Built Her House: Seven Pillars and Seven Councils

The sapiential key to this identification is given explicitly in Scripture: “Wisdom has built her house; she has set up its seven pillars.” (Prov 9:1). Within the Christian tradition, Christ Himself is confessed as the Wisdom of God (1 Cor 1:24), and the Church is understood as His house, built and ordered through divine wisdom rather than human power. Patristic and Byzantine exegesis consistently receive this passage not as poetic ornament, but as theological architecture: Wisdom establishes her dwelling through order, stability, and completeness.²⁰

Within Orthodox historicist reading, the seven pillars are rightly understood as corresponding to the Seven Ecumenical Councils, through which the Church bore authoritative witness to the identity of Christ. These councils—many of them held in Constantinople itself, and the rest within its immediate conciliar orbit—constitute the completed testimony of the Church concerning the Incarnation.²¹ Cyril Lavriotis explicitly links the Two Witnesses of Revelation 11 to this conciliar and ascetical testimony of the Church, exercised corporately by clergy and laity, bishops and confessors.²² The Seven Thunders of Revelation 10, which utter their voices and are then sealed, correspond to this completed conciliar confession: once the dogmatic witness is finished, no new thunder is added.

Thus Hagia Sophia, dedicated to Holy Wisdom, stands not only as a monument, but as a material confession of Proverbs 9:1. Wisdom has built her house in the Queen of Cities; she has set up her seven pillars through the councils; and that house stands upon a square foundation, the πλατεῖα, where testimony is rendered and judged.

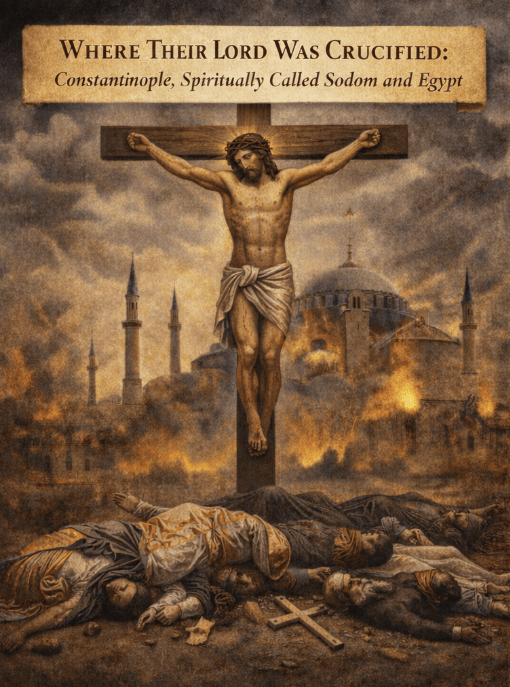

V.4 “Where Their Lord Was Crucified”: Ecclesial Crucifixion in History

Revelation 11:8 further declares that this Great City is the place “where also their Lord was crucified.” The text does not require a literal repetition of Golgotha, but invokes the established biblical principle that Christ identifies Himself with His Body. To persecute the Church is to persecute Christ (Acts 9:4); to expose and silence the Body is to reenact the Passion of the Head.²³ Andrew of Caesarea already emphasizes that the Two Witnesses are not individual prophets alone, but the Church’s corporate testimony subjected to public humiliation.²⁴

In this light, the identification of Constantinople as New Zion and New Jerusalem is not rhetorical excess, but theological continuity. The City in which Christ is confessed as Wisdom, where His identity is defined through councils, and where His Church is publicly silenced and subjected to long captivity, becomes the place of His crucifixion in history. That is, the Church of Holy Wisdom, Hagia Sophia—“where our Lord was crucified”—is identified with the Logos, Jesus Christ, the “Wisdom of God,” within the Great City spiritually and typologically understood as the New Jerusalem. Once the greatest church in all Christendom, Hagia Sophia came to stand, as it were, crucified in history: suspended in time, silenced in worship, and subjected to desecration as an abomination of desolation through its conversion into a mosque. The “dead bodies” lying in the πλατεῖα signify not the annihilation of the Church, but the apparent death of her public voice—the Body of Christ exposed, unburied, and powerless before the nations. Yet, as the Apocalypse insists, this exposure is provisional. As with Christ Himself, crucifixion precedes vindication, and death precedes resurrection.

Conclusion: The Passion of the Church

Revelation 11 is the Passion narrative of the Church. Read within the Orthodox historicist horizon, Revelation 11 does not present an abstract apocalyptic riddle or a distant futurist scenario, but the unveiling of the Church’s lived history as it unfolds in conformity to her Lord. The Two Witnesses, clothed in sackcloth, testify throughout the appointed prophetic period, complete their testimony through conciliar confession, and are then publicly silenced in the πλατεῖα of the Great City. Their death is not annihilation, but exposure; their bodies are not buried, but displayed; and their humiliation is not private, but civic and visible before the nations. In this way the Apocalypse interprets ecclesial history through the pattern already revealed in Christ Himself.

Thus the Apocalypse reveals at its core the great human and ecclesial drama of redemption: as Christ suffered, died, and rose from the dead, so too must His Church. Revelation 11 depicts not a detached future spectacle, but the historical ministry, passion, death, burial, and promised resurrection of the Body of Christ. Through the enduring witness of clergy and laity, the Church gave birth to the Man-Child by means of the Seven Thunders—her conciliar confession of Christ—within the square of the Great City, the Queen of Cities, long hailed as New Zion and New Jerusalem. What is unveiled is not the defeat of the Church, but her conformity to her crucified Lord, whose suffering in history is the necessary prelude to vindication, resurrection, and reign.

In this light, Constantinople and Hagia Sophia emerge not as incidental backdrops, but as providential stages upon which the drama of Revelation 11 is enacted. The square foundation beneath the dome of Holy Wisdom, the completion of conciliar testimony, the long period of oppression and apparent silence, and the promise of renewed life together form a coherent ecclesial narrative. Orthodox Historicism therefore does not impose meaning upon the Apocalypse; it receives the text as a revelation of how Christ continues to act in and through His Church within history. Revelation 11, rightly understood, proclaims that the Church’s suffering is real, her witness costly, and her apparent death public—but that her resurrection, like her Lord’s, is assured by God and revealed in due time.

© 2026 by Jonathan Photius

Footnotes

- Daniel 7; Revelation 11; cf. Andrew of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse, prologue.

- Apostolos Makrakis, Commentary on the Apocalypse, ad Rev 11; Kyrillos Lavriotis, Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse, ed. Asterios Agyriou (Thessaloniki: PIPM, 1985).

- Daniel 7:25; 12:7; Revelation 11:2–3.

- Lavriotis, Les Exégèses, 631–634.

- Makrakis, Commentary, ad Rev 11:2–3.

- On Ottoman emergence: 1299 foundation; 1453 fall of Constantinople.

- Lavriotis, Les Exégèses, 631–633.

- Makrakis, Commentary, ad Rev 11:1.

- Ibid., ad Rev 11:5.

- Makrakis, Commentary, ad Rev 11:8.

- Norman Tanner, Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils, vol. 1 (London: Sheed & Ward, 1990).

- Makrakis, Commentary, ad Rev 11:8.

- Steven Runciman, The Fall of Constantinople 1453 (Cambridge: CUP, 1965).

- Ibid.; prophetic use of Sodom: Isaiah 1; Ezekiel 16.

- LSJ, s.v. πλατεῖα; BDAG, 824.

- Apostolos Makrakis, Ἑρμηνεία τῆς Ἀποκαλύψεως (Athens, 1881), on Rev 11:8.

- Asterios Agyriou, Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse (1453–1821) (Thessaloniki, 1985), 620–628.

- Richard Krautheimer, Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture, 4th ed. (New Haven, 1986), 204–213.

- Robert Ousterhout, Master Builders of Byzantium (Princeton, 1999), 72–85.

- Gregory of Nyssa, On the Making of Man 16; cf. later Byzantine sapiential exegesis on Prov 9:1.

- Norman P. Tanner, Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils, vol. 1 (London, 1990), xv–xxiv.

- Cyril (Kyrillos) Lavriotis of Patras, in Agyriou, Les Exégèses, 630–635.

- Acts 9:4; 1 Cor 12:27.

- Andrew of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse (PG 106:332–336).

Thank You Sir Jonathan

On Fri, Jan 16, 2026, 1:38 AM NEO-Historicism – End Times Eschatology From

LikeLiked by 1 person