Orthodox Historicism, the Two Beasts, and the Eschatological Meaning of 1821

By Jonathan Photius – The NEO-Historicism Research Project

I. Introduction: 1821 as an Unfinished Providential Event

The Greek Revolution of 1821 is commonly interpreted as the decisive moment of national rebirth, marking the end of Ottoman domination and the emergence of the modern Greek state. In Hellenism and the Unfinished Revolution, however, Apostolos Makrakis offers a strikingly different assessment. For Makrakis, 1821 was not a completed liberation but a divinely initiated historical rupture whose deeper purpose remained unrealized. The Revolution succeeded politically while remaining incomplete theologically, having overthrown foreign rule without fully restoring the moral and ecclesial foundations of Orthodox life.¹

Makrakis therefore situates the Greek Revolution within a broader providential horizon. History, in his understanding, is neither accidental nor self-interpreting. It unfolds according to moral–theological laws, governed by divine justice and oriented toward the historical manifestation of Christ’s reign. The Revolution of 1821 belongs to this sacred history, functioning as the opening phase of a longer apocalyptic struggle rather than its culmination.²

II. Core Thesis: Hellenism as Proto-Apocalyptic Theology

Hellenism and the Unfinished Revolution represents Makrakis’ earliest systematic articulation of an Orthodox historicist eschatology, in which modern Greek history is interpreted through categories that later become explicit in his commentary on the Apocalypse. Long before engaging Revelation formally, Makrakis already conceives history as structured by moral causality, prophetic sequence, and providential reversal. The Revolution of 1821 appears as a divinely initiated phase within an extended conflict between Orthodoxy and successive anti-Christian powers, oriented toward a future period of Orthodoxy and the dissolution of illegitimate imperial systems.³

The work should therefore not be read as political rhetoric or romantic nationalism. It functions instead as proto-apocalyptic theology—a theological interpretation of history that anticipates Makrakis’ later historicist exegesis of Revelation, employing its logic before adopting its technical vocabulary.⁴

III. History as a Moral–Apocalyptic Process

Throughout Hellenism, Makrakis presents history as a moral–apocalyptic process, not as a neutral political chronology. Historical events are governed by ἀλήθεια (truth) and δικαιοσύνη (justice), rather than by chance, power, or material necessity. Nations rise and fall according to their conformity—or resistance—to the divine Logos. History advances in discernible stages, not in endless cycles, and judgment unfolds within historical time rather than being postponed exclusively to the final consummation.⁵

This framework reflects a classic Orthodox historicist worldview. Political collapse follows spiritual delegitimation; liberation follows repentance, education (paideia), and moral re-alignment with truth. These same assumptions later structure Makrakis’ apocalyptic interpretation, where trumpets signify historical judgments, beasts represent moral–institutional powers, and the Kingdom denotes Christ’s historical reign manifested through the Church. Hellenism thus provides the conceptual groundwork for his later exegetical system.⁶

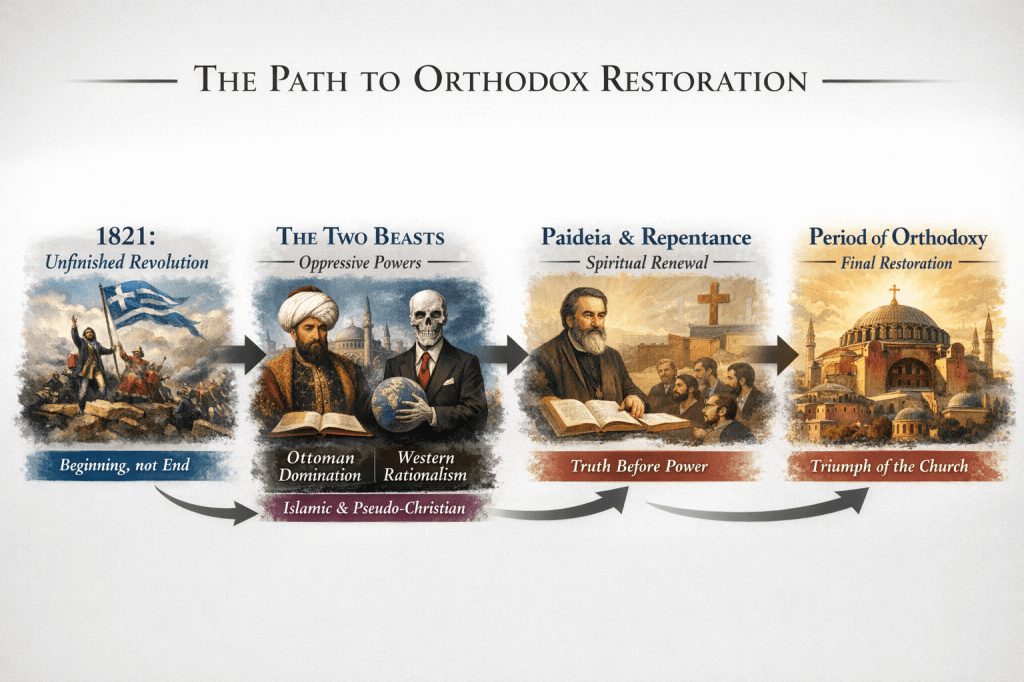

IV. The Revolution of 1821 as an Apocalyptic Event

Makrakis explicitly rejects any interpretation of 1821 as a completed deliverance. The Revolution marks a beginning, a divine summons that initiates a longer historical process. Its incompletion is not a failure of arms but a failure of fulfillment: the moral and ecclesial conditions required for lasting liberation had not yet matured.⁷

Here Makrakis implicitly draws upon biblical patterns of partial restoration. Just as Israel experienced repeated, incomplete deliverances conditioned upon covenantal fidelity, so the Greek people experienced political liberation without full spiritual renewal. The phrase “unfinished revolution” functions as a historicist signal, identifying 1821 as an event embedded within an unfolding prophetic process.⁸

The “spiritual revolution” Makrakis calls for does not negate political struggle but subordinates it to ecclesial transformation. Preparation and consolidation refer not primarily to statecraft but to theological clarity, moral education, and the re-centering of national life upon Orthodoxy. Hellenism itself is redefined not as ethnicity or sentiment, but as a covenantal identity ordered toward Christ.⁹

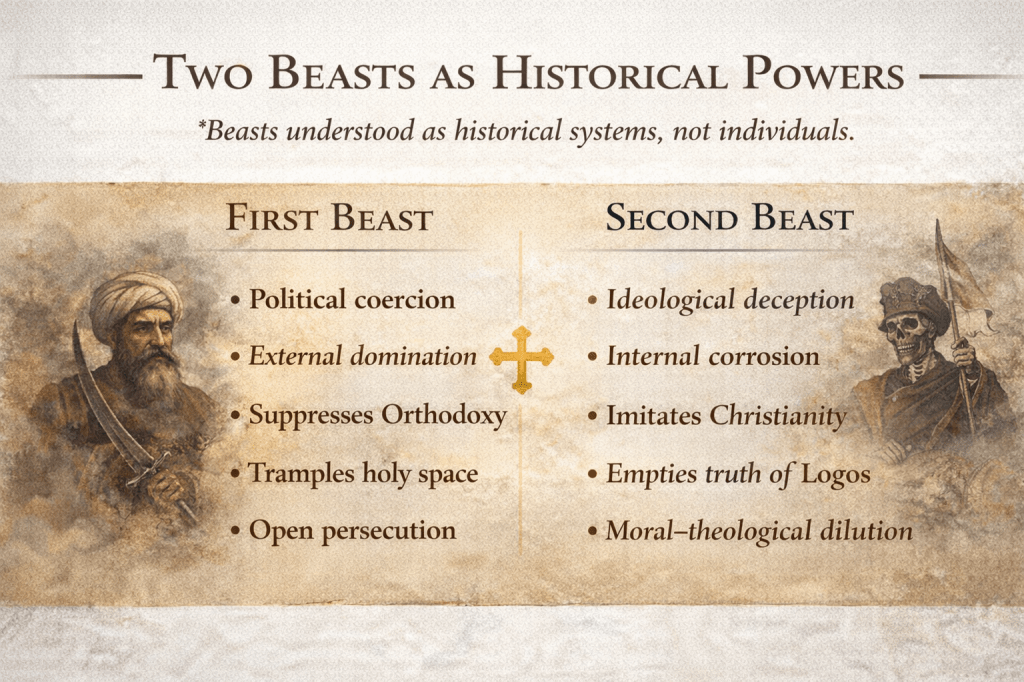

V. The Two Beasts: Implicit but Structurally Present

Although Hellenism and the Unfinished Revolution predates Makrakis’ explicit apocalyptic terminology, its internal structure already presupposes the existence of two successive oppressive systems, corresponding to what Revelation later identifies as the two beasts.¹⁰

The first is a form of anti-Christian political domination, concretely associated with Islamic—and specifically Ottoman—rule. Makrakis characterizes this power by religious coercion, the suppression of Orthodoxy, and the desecration of holy space. This domination functions historically as a prolonged trampling of the sacred inheritance, corresponding to the apocalyptic logic of desolation and oppression found in biblical prophecy.¹¹

The second power is subtler and, in Makrakis’ assessment, more spiritually corrosive. It appears as Western rationalist and pseudo-Christian authority, marked by Enlightenment philosophy severed from the Logos, hypocritical diplomacy, and a conception of civilization emptied of Orthodox truth. This power mimics legitimacy while undermining the foundations of faith, anticipating Makrakis’ later critiques of papal absolutism, secular philosophy, and Protestant fragmentation.¹²

Thus, even without explicit reference to Revelation, Hellenism already assumes a dual-beast framework: one power that persecutes openly, and another that deceives under the guise of progress and civilization.¹³

VI. Completing the Revolution: Makrakis’ Historicist Program

Makrakis does not leave the Revolution suspended in abstraction. He outlines a coherent historicist pathway by which its promise may be fulfilled.

First is paideia, understood as formation in the Logos rather than mere technical education. National repentance, philosophical clarity, and the restoration of Orthodox epistemology are prerequisites for genuine freedom. Truth must precede power.¹⁴

Second comes the recovery of moral legitimacy. Justice precedes victory; authority endures only when grounded in truth. Nations fall when their moral contradictions are exposed.¹⁵

Third is providential timing. Divine action unfolds gradually rather than catastrophically. Judgment ripens before collapse, and liberation arrives quietly yet decisively, according to God’s appointed order.¹⁶

Finally, Makrakis anticipates a period of Orthodoxy, in which Christ reigns historically through His Church. Political liberation follows ecclesial restoration, not the reverse. Constantinople functions here not merely as a political capital, but as an eschatological symbol of restored Orthodox order and unity.¹⁷

This vision is neither chiliastic nor utopian. It reflects a Byzantine post-millennial historicism, in which the Kingdom advances within history through the moral and ecclesial triumph of Orthodoxy rather than through a carnal or speculative millennium.¹⁸

VII. Conclusion: Makrakis and the Recovery of Orthodox Historicism

Hellenism and the Unfinished Revolution reveals Apostolos Makrakis as a pivotal transitional figure in modern Orthodox thought. Long before composing a formal commentary on Revelation, he already interpreted history through an apocalyptic lens shaped by moral causality, providential sequence, and ecclesial centrality. The Greek Revolution of 1821 appears not as an endpoint, but as an inaugural sign within a longer struggle between Orthodoxy and illegitimate powers.¹⁹

Makrakis does not innovate so much as recover. His work preserves a form of Orthodox historicism that reads history itself as a site of divine judgment and redemption, culminating not in speculative futurism or nationalist triumphalism, but in the historical vindication of Christ’s reign through His Church. The Revolution remains unfinished because history itself is still moving—toward truth, justice, and the full manifestation of Orthodoxy in time.²⁰

© 2026 by Jonathan Photius

Footnotes

- Apostolos Makrakis, Hellenism and the Unfinished Revolution (Athens, 19th c.), passim.

- Ibid.; cf. Makrakis’ recurring insistence that political freedom without moral restoration remains provisional.

- See Apostolos Makrakis, Commentary on the Apocalypse (later writings), where these categories are fully systematized.

- On proto-apocalyptic theology as a pre-exegetical category, see Asterios Agyriou, Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse (1453–1821) (Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies, 1982).

- Makrakis, Hellenism, sections on truth (ἀλήθεια) and justice (δικαιοσύνη).

- For Orthodox historicist patterns, see Andrew of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse.

- Makrakis, Hellenism, on the moral incompletion of 1821.

- On partial restoration in biblical history, cf. Ezra–Nehemiah and post-exilic prophetic literature.

- Makrakis, Hellenism, on spiritual versus merely political revolution.

- See Revelation 13 as later interpreted in Makrakis’ mature writings.

- Makrakis, Hellenism, on Ottoman domination and religious coercion.

- Ibid., on Western rationalism and pseudo-Christian civilization.

- Compare Makrakis’ later explicit beast typology in his Apocalypse commentary.

- Makrakis, Hellenism, on education (paideia) and the Logos.

- Ibid., on justice as the precondition of authority.

- Ibid., on providential timing and gradual judgment.

- Makrakis’ symbolic use of Constantinople throughout his corpus.

- For Byzantine post-millennial historicism, see patristic and post-Byzantine apocalyptic traditions.

- Makrakis, Hellenism, read in continuity with his later apocalyptic works.

- On Orthodox historicism as an alternative to futurism and nationalism, see modern Neo-Historicist scholarship.

Historiographical Note. Apostolos Makrakis is sometimes read within the category of nineteenth-century Greek nationalism; however, such a classification risks obscuring the fundamentally theological character of his historical vision. Unlike secular nationalist thinkers who grounded Greek identity in ethnicity, language, or Enlightenment political theory, Makrakis consistently subordinated Hellenism to Orthodoxy, treating national history as intelligible only within a providential and moral framework governed by divine justice. His critique of Western rationalism, insistence on paideia rooted in the Logos, and interpretation of the Greek Revolution as an unfinished spiritual process place him closer to the Orthodox historicist tradition than to modern nationalist ideology. This distinction is essential for situating Hellenism and the Unfinished Revolution as proto-apocalyptic theology rather than political romanticism.