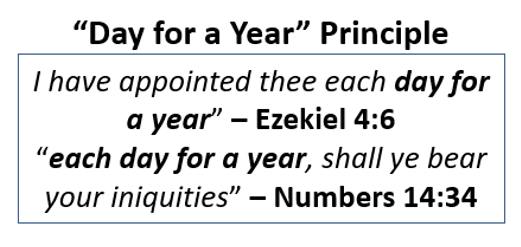

Neilos Sotiropoulos (†1999) represents one of the last major Greek Orthodox historicist interpreters of prophecy in the twentieth century, standing consciously within the lineage of Byzantine and post-Byzantine apocalyptic exegesis. He was a hieromonk at the Simonpetra monastery at Mt. Athos from the 1950s to the 1990s. Writing in the shadow of two world wars, the Cold War, and the geopolitical reconfiguration of the Near East, Sotiropoulos sought to demonstrate that biblical prophecy—especially Daniel and Revelation—unfolds across real, datable Church history, rather than being confined either to the first century or postponed entirely to a speculative futurist end-time.¹

His major work, The Coming Sharp and Two-Edged Sword (1973), functions as both a warning sermon and a historicist synthesis, drawing together Scripture, patristic prophecies, and chronological calculation.²

Core Hermeneutical Principles

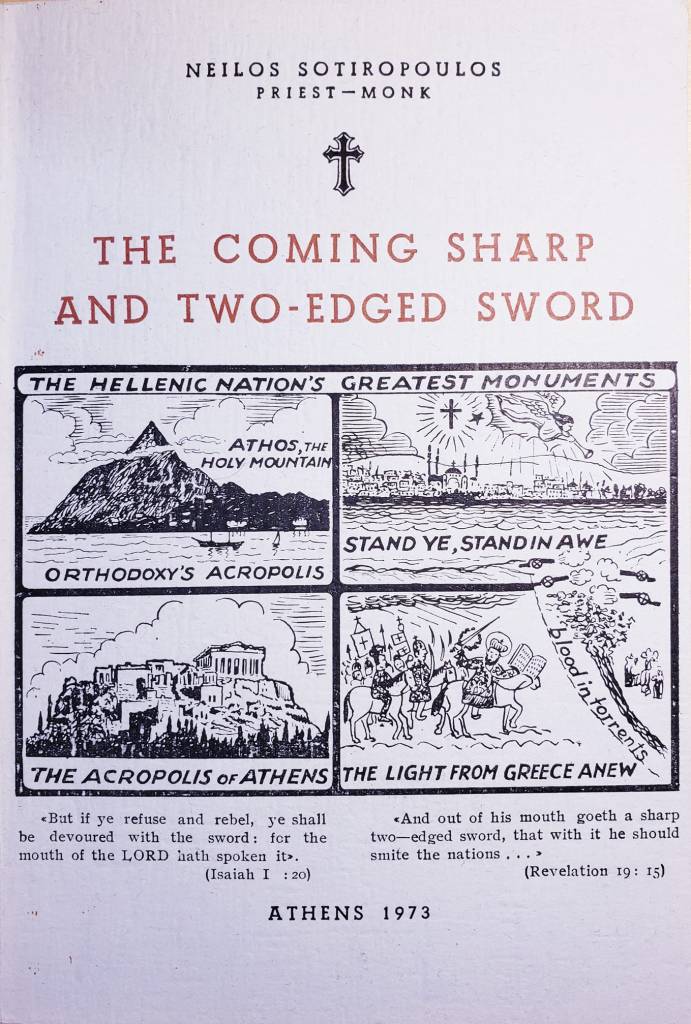

1. The Day-Year Principle as Orthodox Tradition

Following Ezekiel 4:6 and Numbers 14:34, Sotiropoulos insists that prophetic “days” signify historical years, a principle he explicitly roots in Orthodox patristic usage rather than Protestant innovation. Daniel’s seventy weeks, the 1260 days, the 1290 and 1335 days, and Revelation’s forty-two months are all treated as synchronized historical periods spanning centuries, not literal days.³

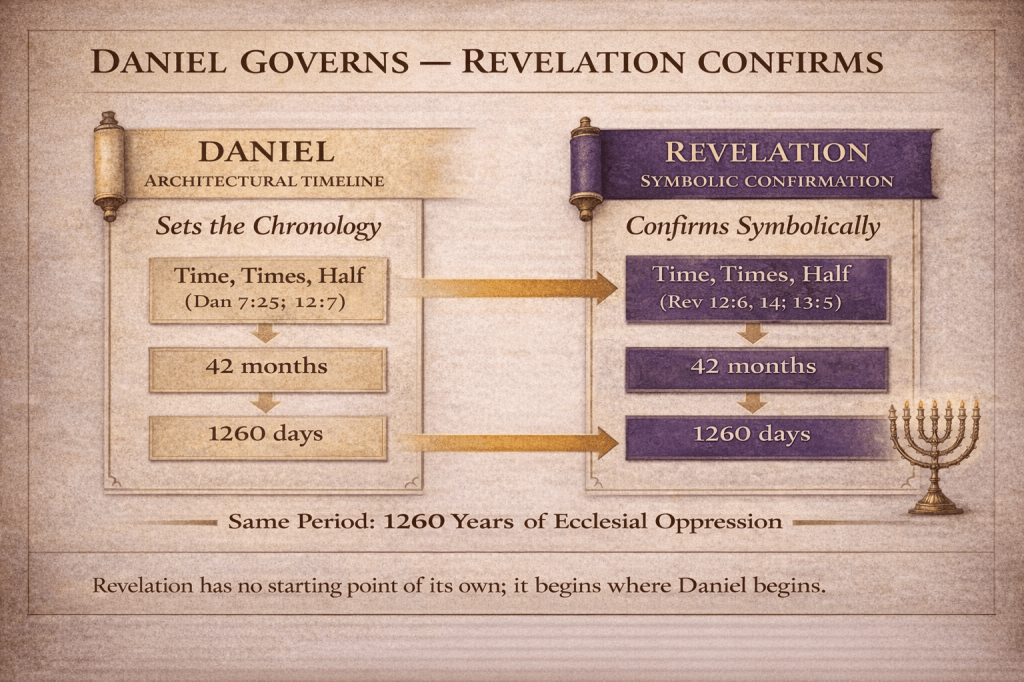

2. Daniel and Revelation as a Unified Chronological System

For Sotiropoulos, Daniel provides the chronological starting points, while Revelation supplies parallel confirmations. He repeatedly stresses that Revelation’s numerical data cannot be interpreted independently of Daniel. Together, the two books describe the long reign of hostile powers, the persecution and preservation of the Church, and the eventual triumph of Christ’s Kingdom within history, not outside it.⁴

Daniel 9 and the Structure of History

Daniel’s Seventy Weeks form the backbone of Sotiropoulos’ eschatology. He interprets them as a continuous historical span, not a fragmented scheme interrupted by a prophetic “gap.” In his reading, the weeks extend from the Persian decrees through the First Advent of Christ, continue through the long age of ecclesial struggle, and culminate in the collapse of hostile powers and the vindication of Orthodoxy.⁵

Crucially, Sotiropoulos correlates Daniel 9 with later prophetic cycles—especially those tied to Jerusalem and Constantinople—arguing that sacred history revolves around two covenantal centers: Jerusalem, the birthplace of Christ according to the flesh, and Constantinople, the historical bearer of Christ’s Name and Orthodox confession.⁶

While fully affirming the traditional Christological fulfillment of the Seventy Weeks in the Incarnation, Passion, and the Roman destruction of Jerusalem, Sotiropoulos also argues that the internal structure of Daniel 9 permits a secondary historical application beginning with the Cyrus decree (536/537 BC).⁷ Employing the day-year principle, he understands the sixty-nine weeks as sixty-nine periods of thirty-six years, yielding a total span of 2484 years terminating in 1948 AD. He does not regard the prophecy as closed at that point, but as continuing within the final week as an open historical process.

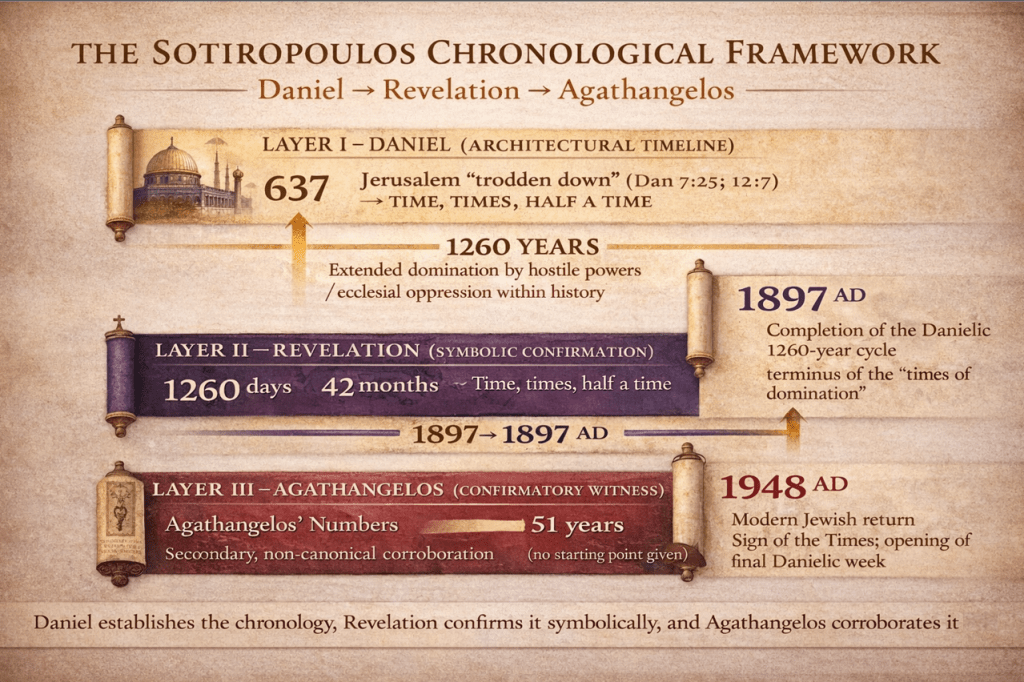

Daniel, Revelation, and the 1260-Year Chronology

A central component of Sotiropoulos’ historicism is his explicit identification of the 1260-year prophetic period as the primary chronological bridge uniting Daniel and the Apocalypse. He insists that Revelation introduces no independent calendar, but presupposes the starting point already supplied by Daniel.⁸

Sotiropoulos anchors this period to 637 AD, the year Jerusalem fell to the Mohammedan Arabs and the so-called Omar Temple was erected on the Temple Mount. He identifies this event with the “abomination of desolation” and the beginning of Jerusalem being “trodden down,” in accordance with Daniel’s prophecy of “a time, times, and half a time” (Dan 7:25; 12:7).⁹ Interpreting this period according to the Orthodox day-year principle, he understands the 1260 days, 42 months, and time, times, and half a time of Revelation (Rev 11:2–3; 12:6; 13:5) as referring to the same extended historical epoch.¹⁰

From this starting point, Sotiropoulos performs a direct calculation:

637 AD + 1260 years = 1897 AD

He repeatedly identifies 1897 as the terminus of Revelation’s chronology and the end of the divinely allotted duration of the Mohammedan beast’s dominance.¹¹ This date does not signify the end of history, but the completion of a prophetic period of domination, after which the power of hostile systems begins to wane. He explicitly states that Revelation’s chronology “has no starting point of its own,” because its beginning is already given by Daniel in the year 637.¹²

Having established 1897 as the completion point of the Daniel–Revelation cycle, Sotiropoulos then turns to the Byzantine prophetic tradition—particularly Agathangelos—as a secondary and corroborative witness. Agathangelos’ prophecies contain numerical periods, notably fifty-one years, but provide no explicit starting point. Sotiropoulos supplies this anchor by identifying 1897 as the natural terminus from which Agathangelos’ numbers proceed.¹³

Accordingly, he calculates:

1897 + 51 years = 1948 AD

Sotiropoulos explicitly identifies 1948, the year of the modern Jewish return, as a “Sign of the Times” and correlates it with Daniel’s Seventy Weeks, asserting that the sixty-nine weeks reach their completion at that point and that the final week begins thereafter.¹⁴ He does not present this convergence as speculative prediction or an eschatological endpoint, but as further historical confirmation that Danielic chronology continues to unfold within history.

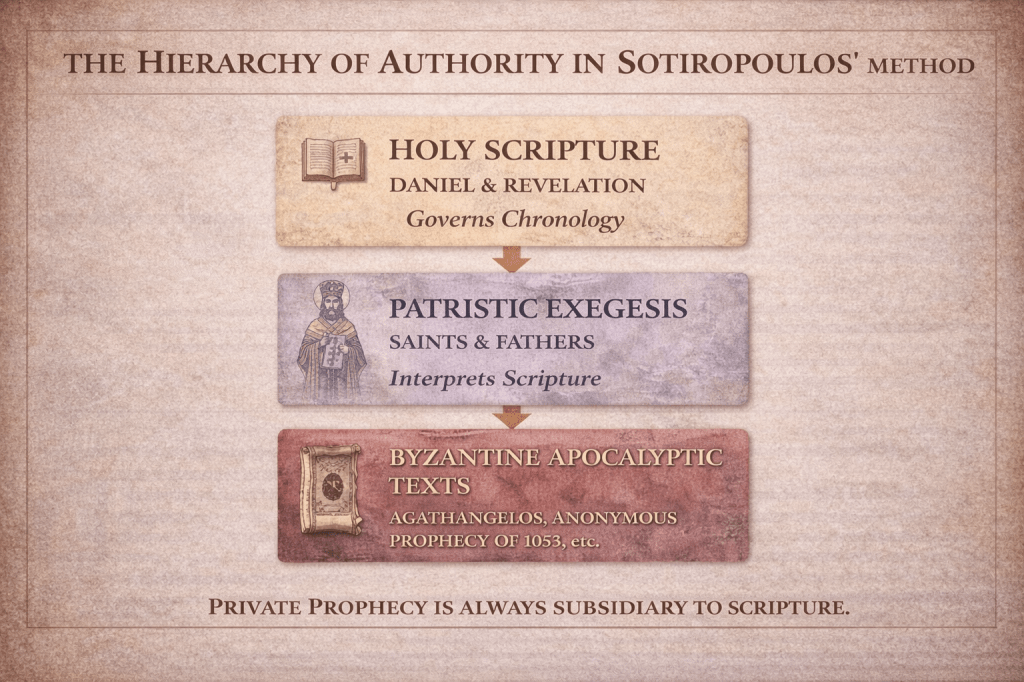

Throughout this discussion, Sotiropoulos maintains a clear methodological hierarchy: Daniel establishes the chronology, Revelation confirms it symbolically, and Byzantine prophecy corroborates it secondarily. Private prophecy is never permitted to govern Scripture, but may function as historical testimony when it converges coherently with biblical chronology and lived ecclesial history.¹⁵

Daniel–Revelation Period Equivalence Chart

| Daniel | Revelation | Symbol | Historical Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dan 7:25 | Rev 13:5 | Time, times, half | 1260 years |

| Dan 12:7 | Rev 12:6 | 1260 days | Same period |

| — | Rev 11:2 | 42 months | Same period |

Two Beasts, Two Spheres Chart

| Beast | Sphere | Historical Expression |

|---|---|---|

| First Beast | Political–religious power | Islam |

| Second Beast | Ecclesial authority | Papacy |

Integrating the Byzantine Apocalyptic Tradition into Historicist Eschatology

A distinctive feature of Sotiropoulos’ eschatology is his sustained effort to integrate the Byzantine apocalyptic tradition into a unified historicist framework governed by Scripture. Unlike modern prophetic speculation, he does not treat post-biblical prophecies as independent revelations or parallel authorities, but as secondary witnesses that illuminate, confirm, and localize the biblical prophetic timeline already established by Daniel and Revelation.¹⁶

Within The Coming Sharp and Two-Edged Sword, Sotiropoulos repeatedly draws upon Agathangelos, the Anonymous Prophecy of 1053, Methodius of Patara, Andrew the Fool for Christ, and the prophecy associated with Prophecy on Constantine’s Tomb. These texts do not introduce new doctrines, but rearticulate the same historical conflict symbolized in Revelation 13—the long struggle between the Church and dominant anti-Christian powers.¹⁷

Sotiropoulos interprets this tradition as consistently bearing witness to the two historic beasts of Revelation 13: the Mohammedan power, which subjugated the Christian East from the seventh century onward, and the Papal system, which in his view distorted ecclesial authority and doctrine within the Christian West.¹⁸ The Byzantine prophecies are therefore read as historical commentaries in symbolic form, describing the rise, reign, and eventual collapse of the same powers already identified through biblical exegesis.¹⁹

In this synthesis, the Byzantine texts function in three ways: they localize prophecy geographically around Jerusalem and Constantinople, extend chronology narratively across centuries of oppression and delay, and converge eschatologically in anticipating a historical reversal in which hostile powers undermine one another and Orthodoxy is vindicated through divine judgment acting within history.²⁰

Sotiropoulos remains careful to subordinate these prophecies to Scripture, insisting that their coherence and convergence justify only a cautious corroborative role.²¹ In doing so, he stands firmly within the Orthodox tradition that preserved such texts without elevating them to dogma.²² By reconciling the Byzantine apocalyptic corpus with Danielic and Johannine chronology, Sotiropoulos sought to recover a distinctively Orthodox historicist memory, in which Revelation 13 unfolds across the lived experience of the Church between the First and Second Advents.²³

Identification of the Beasts and Antichrist Systems

In line with older Orthodox historicism, Sotiropoulos interprets the Beasts of Daniel and Revelation corporately rather than as a single future individual. The Mohammedan power and the Papal system function as long-standing historical adversaries of the Orthodox Church, while secular ideologies appear as derivative manifestations of the same anti-Christian principle.²⁴

The number 666 is therefore not futuristic speculation, but something that becomes intelligible only through historical realization, echoing Andrew of Caesarea’s insistence that time itself reveals the meaning of prophecy.²⁵

The Kingdom of God in History

Sotiropoulos’ eschatology is fundamentally post-tribulational and restorative. After the collapse of hostile systems, he anticipates the cessation of war, the vindication of Orthodoxy, and a historical period in which Christ reigns through His Church—anticipating the eschaton while remaining within history.²⁷

Significance for Neo-Historicism

Neilos Sotiropoulos stands as a critical twentieth-century bridge figure, inheriting the chronological historicism of Christophoros Angelos, Anastasios Gordios, John Lindeos of Myra, Theodoret of Ioannina, Cyril Lavriotis and Apostolos Makrakis, reasserting the legitimacy of Orthodox prophetic year/day calculation, and preparing the ground for later Greek Orthodox Historicist refinement of Daniel 9 as a continuous ecclesial timeline.²⁸

© 2026 by Jonathan Photius

Chicago-Style Footnotes

- Neilos Sotiropoulos, The Coming Sharp and Two-Edged Sword (Athens, 1973), Preface.

- Ibid., Parts I–III.

- Ibid., Part II, chap. 1.

- Ibid., Part II, chaps. 1–2.

- Ibid., Part II.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Neilos Sotiropoulos, The Coming Sharp and Two-Edged Sword (Athens, 1973), Part III.

- Ibid., discussion of Jerusalem’s fall in 637 and Daniel 7; 12.

- Ibid.; cf. Rev 11–13 interpreted through the day-year principle.

- Ibid., explicit calculation of 637 + 1260 = 1897.

- Ibid., statement that Revelation’s chronology begins where Daniel begins.

- Ibid., treatment of Agathangelos’ numerical prophecies.

- Ibid., correlation of 1897 + 51 = 1948 with Daniel 9.

- Ibid., Preface and concluding chapters on the subordination of private prophecy.

- Ibid., passim.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., Part III.

- Ibid., Preface and Part I.

- Ibid., Part II.

- Ibid., Part III.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., Preface.

- Andrew of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse, cited by Sotiropoulos, Sharp and Two-Edged Sword.

- Sotiropoulos, Sharp and Two-Edged Sword, concluding chapters.

- Ibid.; continuity with Makrakis implied throughout.