By Jonathan Photius – The NEO-Historicism Research Group

Introduction

In contemporary Orthodox discussions, chiliasm—the expectation of a historical millennium derived from Revelation 20—is frequently dismissed as having been condemned by the Ecumenical Councils, most often by appeal to the First Council of Constantinople (381) and the Niceno–Constantinopolitan Creed. This claim is often presented as settled fact, functioning as a theological boundary marker rather than a historical conclusion.¹

Yet when the conciliar record is examined carefully, this assertion proves unsustainable. No Ecumenical Council ever issued a canon, anathema, or doctrinal definition condemning chiliasm as such. At the same time, it is equally undeniable that chiliasm gradually fell out of favor in the Church during the late fourth and fifth centuries. The critical question, therefore, is not whether chiliasm declined, but why—and whether that decline resulted from conciliar judgment or from broader historical, theological, and political developments.²

I. Framing the Question Correctly: Dogma versus Interpretation

Orthodox theology has always distinguished carefully between dogma, defined conciliarity and binding upon the Church, and theological interpretation, which may enjoy wide reception without ever becoming dogmatic.³ Eschatological interpretation—especially the symbolic reading of apocalyptic texts—has historically belonged to the latter category.

The Church has defined Christology and Trinitarian theology with precision; she has never defined a single, binding eschatological timetable. Claims that chiliasm was “condemned” often arise from a failure to maintain this distinction, conflating later theological consensus with conciliar decree.⁴

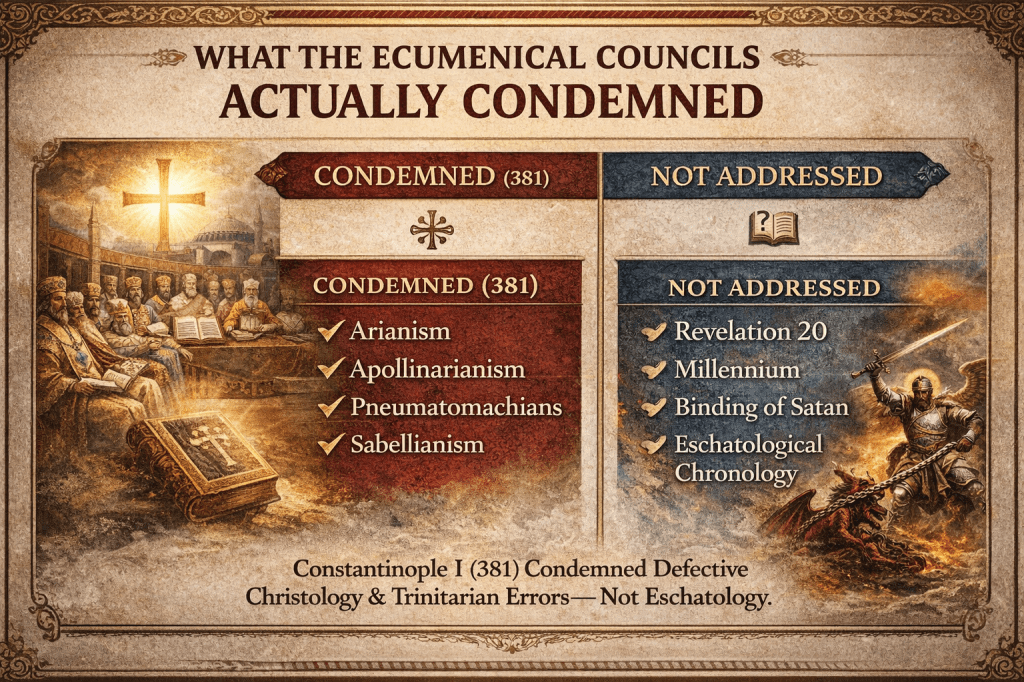

II. What Constantinople I (381) Actually Condemned

The First Council of Constantinople must be understood within its historical purpose. Convened in the aftermath of the Arian crisis, its primary aim was the defense and clarification of Nicene Trinitarianism and Christology. Every condemnation issued by the council fits squarely within this framework.⁵

A. The Condemnation of Apollinaris of Laodicea

Apollinaris of Laodicea was anathematized because of a specific and grave Christological error. He taught that in the Incarnation the divine Logos replaced the rational human soul (νοῦς) in Christ. According to this view, Christ possessed a human body animated directly by the Word but lacked a fully rational human mind.⁶

The implications were severe. If Christ did not assume a complete human nature—including rational soul—then humanity was not fully redeemed. The Incarnation would be partial, and salvation incomplete. For this reason, Apollinarianism struck at the heart of soteriology.⁷

Crucially, this Christological defect is the sole reason Apollinaris was condemned. There is no evidence in the canons, acts, or conciliar correspondence that any eschatological opinions attributed to Apollinaris—whether millennial or otherwise—were discussed, evaluated, or even mentioned.⁸

Indeed, every group condemned in Canon 1 of Constantinople I—Arians, Eunomians, Pneumatomachi, Sabellians, Marcellians, and Apollinarians—was condemned for errors concerning the Trinity or the Incarnation. There is not a single exception.⁹

There is therefore no historical basis for the claim that chiliasm was condemned indirectly through Apollinaris. Such a claim requires importing later controversies into a council whose agenda was explicitly Christological.¹⁰

B. The Silence of the Council on Eschatology

Equally important is what Constantinople I does not do. The council does not mention Revelation 20, the millennium, the binding of Satan, or eschatological chronology of any kind.¹¹

This silence is not accidental. Councils spoke precisely when dogma was at stake. Where they were silent, later theologians must resist the temptation to retroactively insert judgments the Church herself never articulated.¹²

III. “His Kingdom Shall Have No End”: What the Creed Actually Means

A second argument frequently advanced against chiliasm appeals to the Niceno–Constantinopolitan Creed, specifically the clause:

“And His kingdom shall have no end.”

This phrase is often presented as a decisive anti-millennial statement. Historically, however, its intent is quite different.¹³

A. The Christological Context: Marcellus of Ancyra

The clause was introduced to oppose the theology of Marcellus of Ancyra, who taught that Christ’s reign—and even His personal hypostasis—would cease at the end of time. Appealing to 1 Corinthians 15:24–28, Marcellus argued that once the Son handed the Kingdom back to the Father, the Son’s distinct reign would terminate.¹⁴

Such a view implied not merely an eschatological error, but a defective doctrine of God. If the Son’s reign were temporary, then His divinity itself would be provisional. The Trinity would collapse into a monad.¹⁵

In response, the Church affirmed—using the language of Luke 1:33—that the Son’s reign is eternal and that His kingship does not terminate. This affirmation safeguards Christology, not apocalyptic chronology.¹⁶

Significantly, this anti-Marcellian use of Luke 1:33 is attested decades before Constantinople I, particularly in the catechetical lectures of Cyril of Jerusalem.¹⁷ The clause belongs to a Christological debate, not a polemic against chiliasm.¹⁸

B. What the Creed Affirms—and What It Does Not Define

The theological distinction is decisive. The Creed affirms:

- the eternity of Christ’s kingship,

- the non-cessation of the Son’s reign, and

- the permanence of Trinitarian distinction.¹⁹

It does not define:

- the historical mode of Christ’s reign,

- the symbolic structure of Revelation 20, or

- the relationship between ecclesial history and eschatological fulfillment.²⁰

A temporal millennium does not imply that Christ’s Kingdom ends. A historical phase of intensified ecclesial victory can exist within an unending Kingdom without contradiction.²¹

IV. Why Chiliasm Declined Despite the Absence of Condemnation

If chiliasm was not condemned by councils or creed, why did it disappear from the Church’s dominant theological imagination?

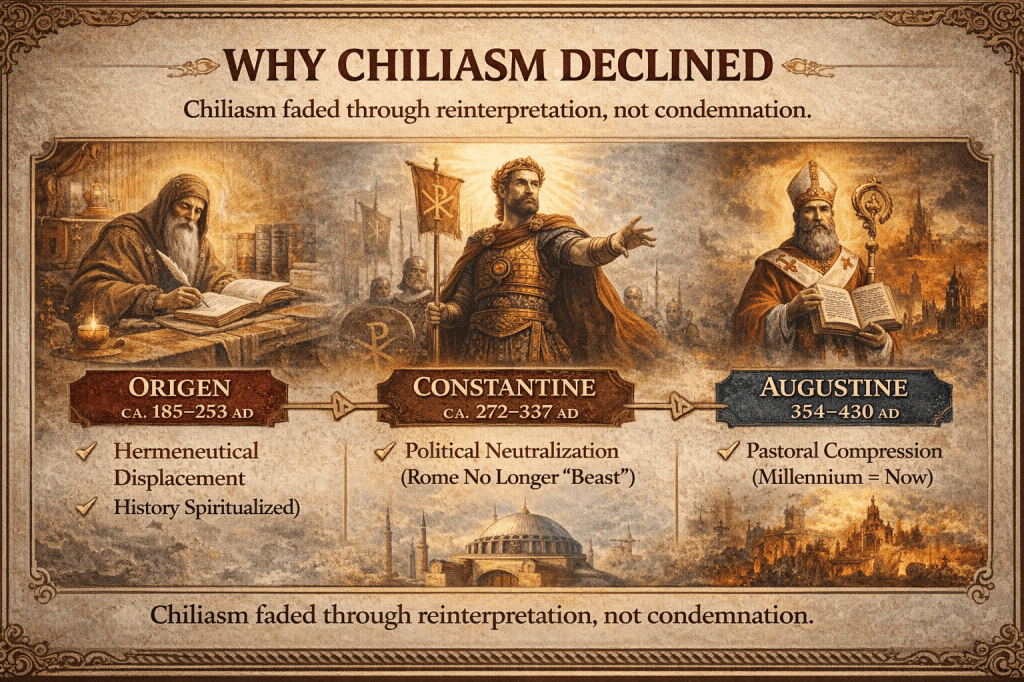

A. Origen and the Reframing of History

With Origen of Alexandria, a decisive hermeneutical shift occurred. Origen did not refute chiliasm exegetically, nor did he denounce it as heresy. Instead, he reconfigured the theological meaning of history itself.²²

Within Origen’s framework, material existence became provisional, history a pedagogical stage, and eschatological fulfillment a process of spiritual ascent rather than historical transformation. Once history ceased to be the primary arena of redemption, a historical millennium became unnecessary. Chiliasm was not disproven; it was displaced.²³

B. Constantine and the Neutralization of Apocalyptic Expectation

The reign of Constantine the Great altered the Church’s historical experience. Chiliasm had flourished under persecution, when the empire appeared self-evidently hostile to Christ. With the end of persecution and the public identification of imperial power with Christianity, that context dissolved.²⁴

Rome could no longer easily be read as Babylon. The Kingdom of Christ appeared, at least outwardly, to have become manifest in history with the rise of the imperial church. Apocalyptic urgency diminished—not because Scripture had changed, but because historical circumstances had.²⁵

C. Augustine and the Pastoral Compression of Time

By the time of Augustine of Hippo, chiliasm had already receded. Augustine did not anathematize chiliasts, nor did he claim conciliar authority for his interpretation. He explicitly tolerated millennial belief so long as it avoided carnal or politically disruptive forms.²⁶

His lasting influence lay in redefining the millennium as the present age of the Church. This pastoral solution addressed real fourth- and fifth-century concerns, but it represented theological development, not dogmatic closure.²⁷

Conclusion

Chiliasm did not fall because the Church condemned it. It fell because history itself was reinterpreted. Origen reframed the theological meaning of time, Constantine transformed the Church’s historical situation, and Augustine offered a pastorally compelling synthesis that gradually became dominant.²⁸

The Ecumenical Councils never defined a single eschatological timetable. What they condemned were Christological distortions—not historical interpretations of apocalyptic symbolism. Recognizing this distinction is essential for theological honesty and for recovering a more accurate understanding of the Church’s eschatological inheritance.²⁹

© 2026 by Jonathan Photius

Footnotes

- Francis X. Gumerlock, “Millennialism and the Early Church Councils: Was Chiliasm Condemned at Constantinople?” Fides et Historia 36, no. 2 (2004): 83–95.

- D. H. Kromminga, The Millennium in the Early Church (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1945), 95–109.

- John Meyendorff, Byzantine Theology (New York: Fordham University Press, 1979), 7–10.

- Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian Tradition, vol. 1 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), 129–31.

- Norman P. Tanner, Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1990), 31–36.

- Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion 77.

- J. N. D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, 5th ed. (London: A&C Black, 1977), 292–96.

- Gumerlock, “Millennialism,” 88–90.

- Tanner, Decrees, 31.

- Pelikan, Christian Tradition, 1:130.

- Tanner, Decrees, 31–36.

- Meyendorff, Byzantine Theology, 96–98.

- Gumerlock, “Millennialism,” 90–93.

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Against Marcellus 2.4.

- Rebecca Lyman, “Marcellus of Ancyra,” in Encyclopedia of Early Christianity, ed. Everett Ferguson (New York: Garland, 1997), 713–14.

- Luke 1:33; Kelly, Early Christian Creeds, 3rd ed. (London: Longman, 1972), 334–36.

- Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures 15.27–28.

- Gumerlock, “Millennialism,” 92–93.

- Kelly, Early Christian Creeds, 341.

- Pelikan, Christian Tradition, 1:129.

- Kromminga, Millennium, 104–05.

- Origen, De Principiis 2.11.

- Kromminga, Millennium, 104–07.

- Eusebius, Life of Constantine 2.28–29.

- Kromminga, Millennium, 108–09.

- Augustine, City of God 20.7.

- Kromminga, Millennium, 109.

- Pelikan, Christian Tradition, 1:131–33.

- Meyendorff, Byzantine Theology, 208–10.