Preface

The following study is offered not as a polemical exercise nor as an attempt to provoke speculative fear, but as a theological meditation rooted in Scripture, the Fathers, and the symbolic grammar of the Orthodox Church. Revelation has too often been approached either as a timetable of future events or as a cipher book for identifying enemies. The Church, however, has consistently received the Apocalypse first and foremost as the revelation of Jesus Christ.

This article does not deny the reality of deception, false teaching, or eschatological judgment. Rather, it insists that all discernment begins with Christ Himself. The Beast can only be understood in relation to the Lamb; the false mark only in contrast to the true seal; false wisdom only as an inversion of divine Wisdom. The intent here is to restore that theological order.

Clergy and teachers are encouraged to read what follows not as a final word, but as a proposal situated within the Church’s interpretive tradition—one that seeks to move the faithful away from anxiety-driven speculation and toward Christological clarity, sacramental sobriety, and iconographic vision. If Revelation unsettles us, it is not to frighten us away from Christ, but to draw us more deeply into His revealed glory.

Introduction

Revelation 13:18 has long occupied a central place in apocalyptic interpretation: “Here is wisdom. Let him who has understanding calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of a man, and his number is six hundred sixty-six.” Popular interpretation has overwhelmingly fixated on the number 666, generating a wide range of gematria-based identifications of Antichrist figures—ancient and modern alike. Yet this consensus rests upon a textual assumption that is far from secure.

The earliest extant manuscript evidence for Revelation 13:18—Papyrus 115—records the number not as 666, but as 616. This alternate reading was already known in the second century, acknowledged by Irenaeus of Lyons, though dismissed by him as a scribal error. The persistence of the 616 reading in early textual witnesses and patristic commentary invites renewed theological scrutiny. The present study argues that 616 is not a numerical curiosity, nor merely a variant error, but functions symbolically as a Christological sign within the Apocalypse—one that coheres with Johannine theology, Pauline Christology, and early patristic interpretation.

I. The Textual Problem of 616

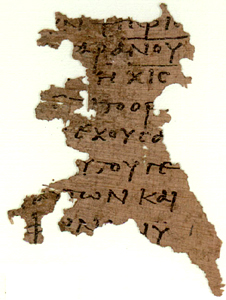

Papyrus 115 (P115), generally dated to the late third or early fourth century, is currently the earliest surviving manuscript fragment of Revelation containing the number in question. It unambiguously reads ΧΙϚ (616). This reading is corroborated by several later witnesses and was known well before the establishment of a standardized textual tradition.

Irenaeus, writing in the late second century (Against Heresies V.30), acknowledges the existence of manuscripts reading 616 but rejects them in favor of 666, arguing that the latter better fits his preferred interpretation (Lateinos). Importantly, Irenaeus does not deny the existence or antiquity of the 616 reading—only its legitimacy. His insistence reveals that the textual issue was already live and contested in the second century.

The question, therefore, is not whether 616 existed, but how it was understood—and whether the theological logic of Revelation itself allows, or even invites, a Christological reading.

II. “Here Is Wisdom”: A Christological Signal

Revelation 13:18 does not introduce its riddle with neutral language. Instead, it announces: “Here is wisdom.” In Scripture, Wisdom is not merely an abstract quality. The Apostle Paul explicitly identifies Christ Himself as the Wisdom of God:

“Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God” (1 Cor 1:24)

“Christ Jesus… became for us wisdom from God” (1 Cor 1:30)

Within the Johannine corpus, this personal understanding of Wisdom aligns seamlessly with the Logos theology of John 1:1. Revelation opens not as a cryptic puzzle book, but as “the Revelation of Jesus Christ” (Rev 1:1). The call to “calculate” is therefore framed by a Christological summons: recognize Wisdom.

Crucially, the text does not say “the number of a beast,” but “the number of a man.” In apocalyptic literature—and especially in Revelation—the designation Man (ἄνθρωπος) cannot be divorced from the title Son of Man, a messianic designation drawn from Daniel 7 and repeatedly applied to Christ throughout the New Testament.

III. 616 as Name, Sign, and Monogram

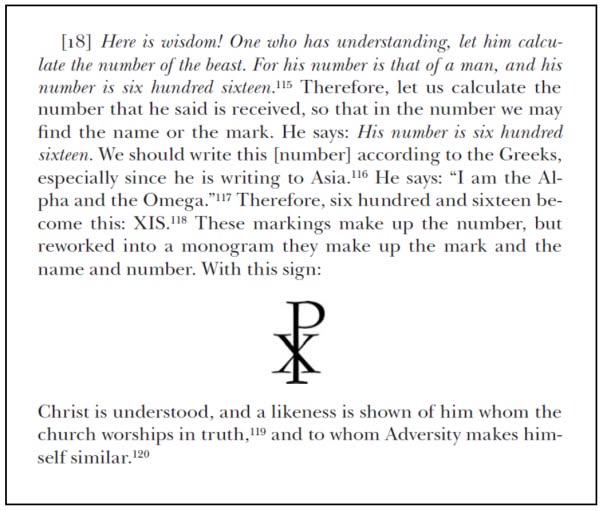

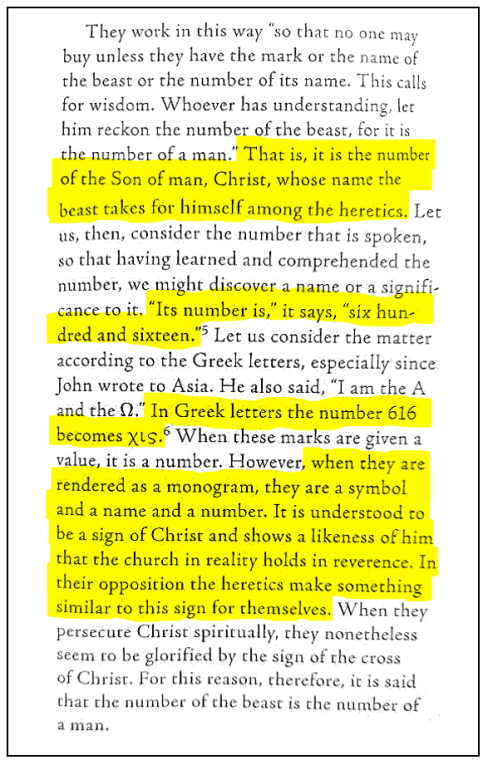

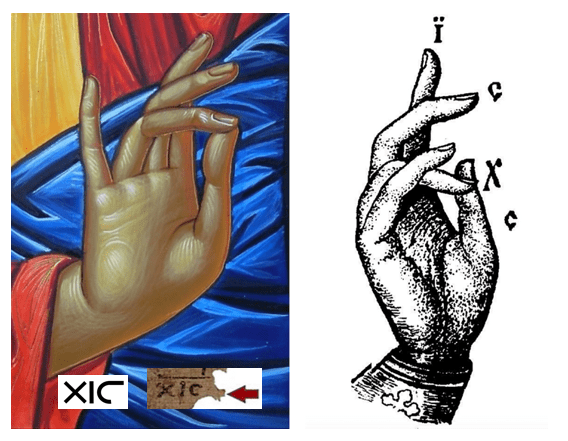

Early patristic interpreters did not approach the number mechanistically. Tyconius, whose Revelation commentary deeply influenced later Latin exegesis, explicitly treats the number as a monogrammatic sign, not a cipher. Writing on Revelation 13:18, Tyconius states that the number can be rearranged into a symbolic mark—one that bears a likeness of Christ, and which the Adversary imitates.

This line of interpretation is developed further by Caesarius of Arles (6th century), who possessed manuscripts reading 616 and makes no reference to 666 as an alternative. Caesarius explicitly identifies the number not as the name of Antichrist, but as a sign associated with Christ Himself, which heretics appropriate falsely. Later Latin commentaries from the early Middle Ages continue this logic, treating the number as both name and sign, capable of being rendered monogrammatically.

When rendered as ΧΙϚ (XIC), the number visually approximates early Christograms, especially when rearranged into cruciform or chi-rho-like configurations. The point is not numerical cleverness, but symbolic resemblance. The number functions the same way icons do: not by exhaustive definition, but by recognizability.

IV. The Mark Before the Mark: Ezekiel and the Tau

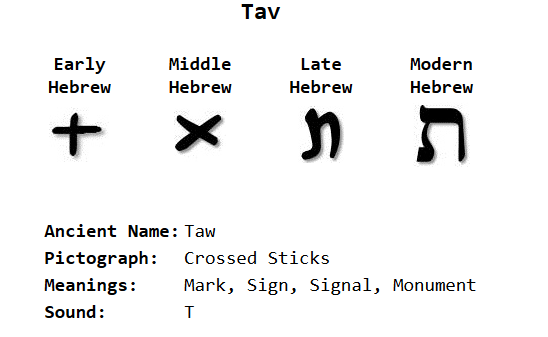

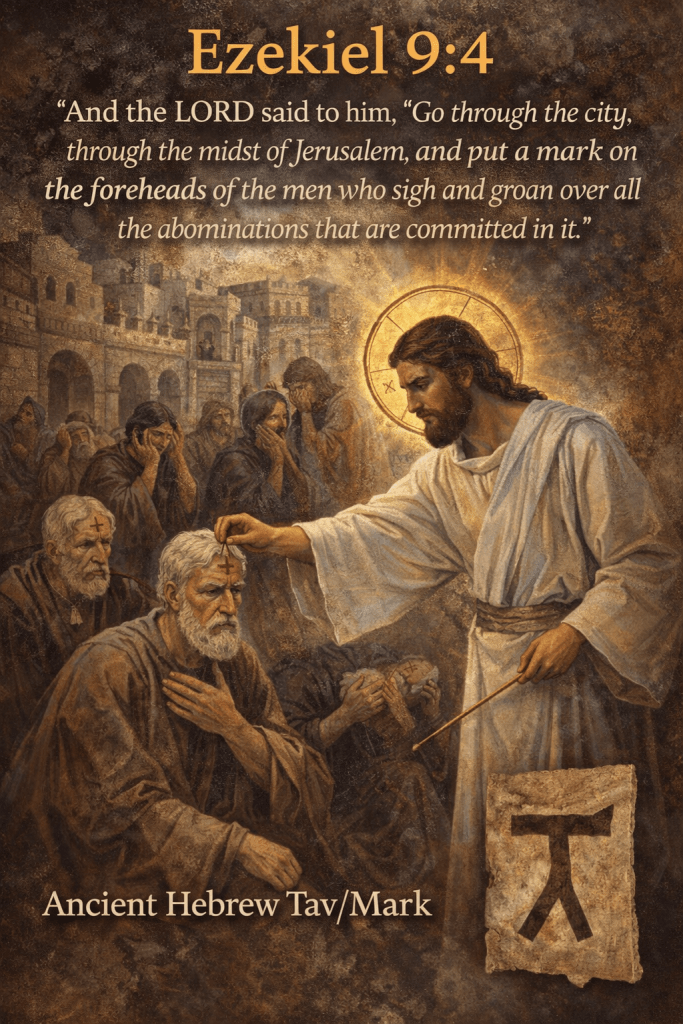

Revelation’s language of “mark,” “seal,” and “forehead” is not novel. It is inherited directly from Ezekiel 9:4, where the righteous are sealed on the forehead with the Tau (Tav)—the final letter of the Hebrew alphabet. In its ancient Paleo-Hebrew form, the Tav was written as a cross-shaped sign, meaning mark, seal, or sign.

Early Christian writers immediately recognized the significance. Tertullian explicitly identifies the Tau with the Cross of Christ, calling it the sign placed upon the faithful. This establishes a decisive biblical principle: the true mark belongs to Christ before it is ever counterfeited.

Revelation preserves this logic. In chapter 7 and again in chapter 14, the servants of God are sealed on their foreheads—not with a number, but with the Name of the Lamb. The Beast’s mark is therefore not primary, but parasitic. It imitates, inverts, and distorts what already belongs to Christ.

V. Inversion, Imitation, and Apocalyptic Grammar

One of the Apocalypse’s consistent themes is counterfeit resemblance. The Beast is described as lamb-like. He does not deny Christ outright; he mimics Him. This principle of inversion explains why false wisdom can appear persuasive: it borrows the external form of truth while reversing its orientation.

Within this symbolic grammar, later historical developments within the post-schism church—such as reversed ritual gestures, inverted signs of the cross, or competing Christological claims—are not accusations in themselves, but expressions of apocalyptic logic. Revelation is concerned less with condemning individuals than with unveiling patterns of imitation.

Thus, 666 functions coherently as a secondary, confirmatory number associated with counterfeit authority (Lateinos), while 616 points to the original Christological sign that is being mirrored. One reveals the true Lamb; the other exposes the false lamb.

Conclusion: Sophia, the Number of a Man, and the Lamb on Mount Zion

The Apocalypse resolves its own riddle. Immediately after the call to Wisdom in Revelation 13:18, St. John writes:

“And I looked, and behold, a Lamb standing on Mount Zion, and with Him those who had His Name written on their foreheads” (Rev 14:1).

The answer to the calculation is not delayed; it is revealed. Wisdom points to the Lamb. The number of a man points to the Son of Man. The mark points to the Name of Christ.

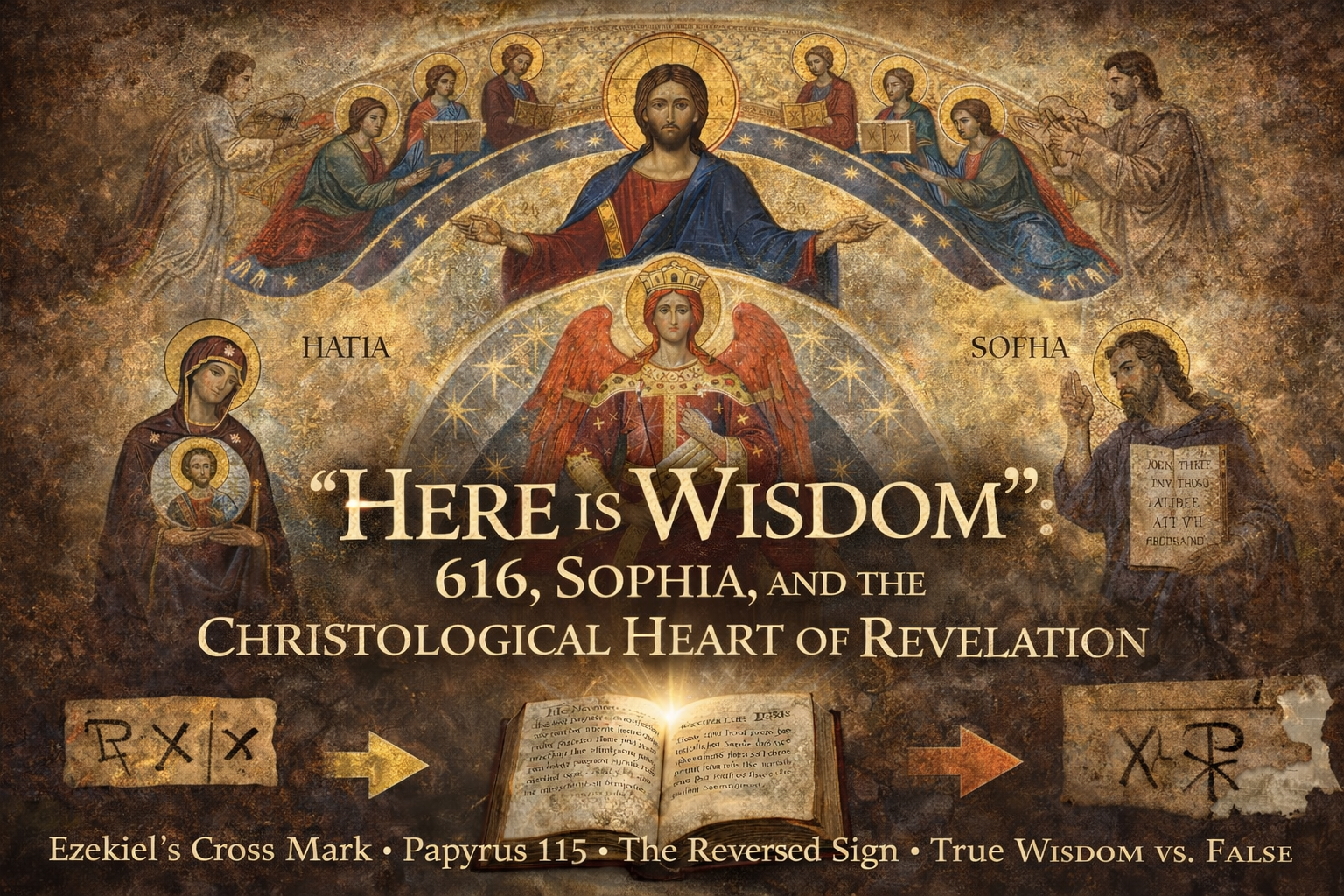

The Orthodox Icon of Sophia, the Wisdom of God, provides a visual theology that gathers these threads into a single confession. Wisdom is not abstract. Wisdom is hypostatic. Wisdom is enthroned. Wisdom is Christ. As Solomon declared, “Wisdom has built her house, and has set up seven pillars” (Prov 9:1)—a theme echoed in Revelation’s sevens: seven spirits, seven stars, seven thunders, seven pillars of the Church’s confession.

Revelation is therefore not primarily a book about identifying Antichrist, but about recognizing Christ. Before there is a false mark, there is a true seal. Before there is counterfeit wisdom, there is Sophia. Before there is the number of a beast, there is the number of a Man—the Theanthropos, the God-Man, the Lamb standing on Mount Zion.

Here is Wisdom.

© 2026 by Jonathan Photius

Methodological Appendix: On Symbolic Interpretation in the Apocalypse

1. Symbol Does Not Mean Subjective

The symbolic interpretation employed in this study is not allegorical arbitrariness. Biblical symbols operate within a stable theological grammar, shaped by earlier Scripture, liturgical usage, and ecclesial reception. Revelation itself declares that it communicates through signs (Rev 1:1), and its imagery consistently draws upon Old Testament types rather than novel inventions.

2. Numbers as Signs, Not Equations

In apocalyptic literature, numbers function symbolically before they function arithmetically. The number seven, for example, is not primarily quantitative but theological. Likewise, Revelation 13:18 explicitly links number, name, and wisdom, indicating that the act of “calculation” is interpretive recognition rather than mathematical computation.

3. Patristic Precedent

Early interpreters such as Tyconius and Caesarius of Arles did not treat the number of the Beast as a puzzle to be solved independently of Christology. Instead, they understood it as a name-number-sign, capable of monogrammatic representation and theological inversion. Their approach legitimizes a symbolic reading grounded in ecclesial theology rather than private speculation.

4. Scripture Interprets Scripture

The method followed here allows earlier biblical texts (e.g., Ezekiel 9; Proverbs 9; Daniel 7) to inform the interpretation of Revelation, rather than isolating the Apocalypse from its scriptural matrix. This is consistent with patristic exegesis and Orthodox liturgical reading practices.

5. Iconography as Theological Exegesis

Finally, Orthodox iconography is treated not as decorative illustration, but as dogmatic theology in visual form. The Icon of Sophia, the Wisdom of God, is not used to generate new doctrine, but to confirm what Scripture already proclaims: that Wisdom is personal, hypostatic, and revealed in Christ. In this sense, the icon functions analogously to patristic commentary—interpreting Scripture by showing it.