A Study in Orthodox Historicist Exegesis and Prophetic Method

By: Jonathan Photius, The NEO-Historicist Research Project

Abstract

Theodoret of Ioannina composed a commentary on the Book of Daniel in 1813–1814 that has not survived as an independent text. Modern scholarship, relying primarily on Asterios A. Agyriou’s Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse, has acknowledged its existence but has not attempted a systematic reconstruction of its contents. This article argues that the Daniel commentary was not destroyed but effectively lost through ecclesiastical non-authorization and non-circulation, and that its essential structure can be reconstructed with high confidence from Theodoret’s later Conjoined Exegesis of the Old and New Testament (1817), his Apocalypse commentary, and contemporary Orthodox historicist parallels. The reconstruction reveals a sophisticated Danielic framework that positions Daniel as the chronological skeleton of sacred history, integrates long-duration prophetic periods, and employs a dual-Antichrist schema that differentiates internal ecclesial corruption from external imperial oppression. The study concludes by situating Theodoret’s method in relation to modern Neo-Historicist interpretations of Daniel.

1. Introduction: The Problem of the Missing Daniel Commentary

Among the exegetical works attributed to Theodoret of Ioannina, the most enigmatic is his Exegesis of the Prophecy of Daniel, composed in 1813–1814 and submitted to the Ecumenical Patriarchate for review. Unlike his Apocalypse commentary (1800) or his Conjoined Exegesis of the Old and New Testament (1817), the Daniel commentary has not survived in manuscript or print. Its absence has led some scholars to treat Theodoret’s prophetic system as fragmentary or internally inconsistent.

Yet the testimony preserved in Les Exégèses demonstrates that the Daniel commentary was central to Theodoret’s exegetical project. The present study contends that the loss of the commentary does not preclude its reconstruction. On the contrary, the surviving corpus allows for a coherent and historically grounded recovery of its principal interpretive architecture.

2. Why the Daniel Commentary Was “Lost”

2.1 Patriarchal Evaluation and Methodological Objections

Asterios A. Agyriou preserves the decisive document concerning the fate of the Daniel commentary: the postscript of Patriarch Cyril VI to his letter of 28 December 1814. The Patriarch reports that he examined the notebooks of the Daniel commentary “μετὰ πολλῆς προσοχῆς” and judged the work “νοῦν ἔχον καὶ σώφρον,” yet reproached it for an excessively allegorical method that abstracted Scripture from sacred history.¹

The Greek critique is precise and revealing:

«Ἐξαναγκάζεις ἕκαστον λόγον τῆς Ἁγίας Γραφῆς εἰς ἀλληγορίαν… ἀφαιρούμενος τῆς ἱστορίας, ὁ λόγος γίνεται ψυχρός.»²

This judgment concerns method, not doctrine. There is no evidence of condemnation, confiscation, or destruction.

2.2 Loss Through Non-Circulation

In the Orthodox manuscript culture of the early nineteenth century, works not approved for copying rarely survived. Theodoret did not contest the Patriarch’s judgment. Instead, he reworked the substance of his Danielic system into the more allegorical Conjoined Exegesis (1817). The Daniel commentary was thus displaced rather than destroyed—a fate sufficient to erase it from the manuscript tradition.

3. Daniel as the Chronological Skeleton of Sacred History

Agyriou emphasizes that Theodoret’s prophetic method presupposes Daniel as the temporal framework underlying the Apocalypse. Without Daniel, the Apocalypse risks becoming numerologically arbitrary. With Daniel restored, the system becomes internally coherent.³

This is confirmed by Agyriou’s observation that Theodoret treated prophetic numbers as structural constants operating before and after Christ:

«τὰ αὐτὰ ἀριθμητικὰ σχήματα ἐνεργοῦσι πρὸ καὶ μετὰ τὴν Ἐνανθρώπησιν.»⁴

Daniel thus governs sacred history as a continuous, providential process rather than a closed pre-Christian prophecy.

4. Reconstructed Exegesis of Daniel

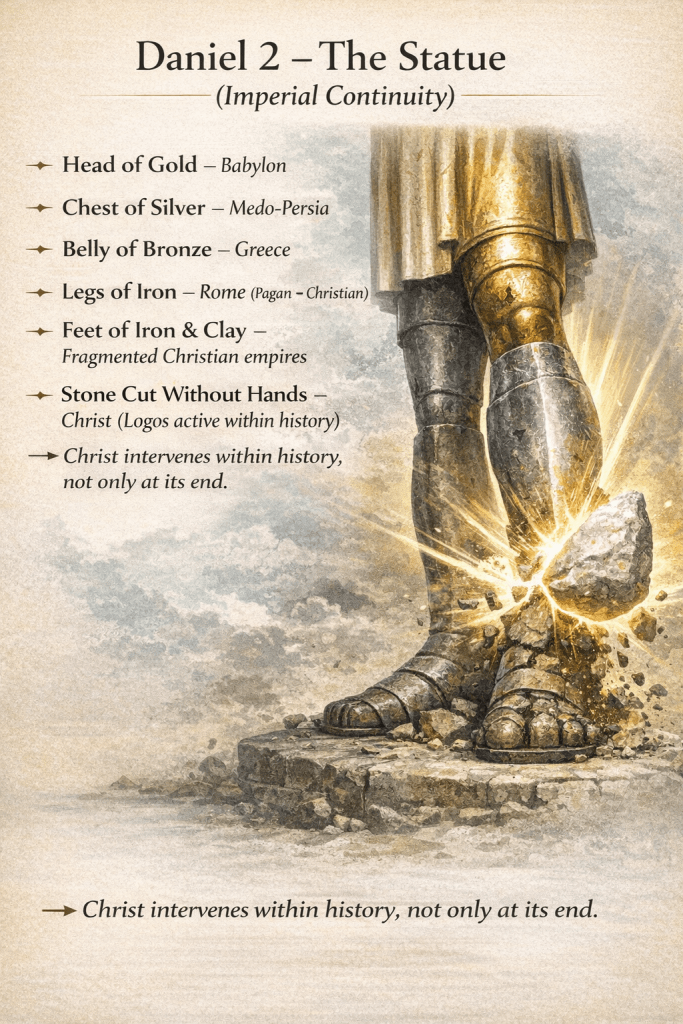

4.1 Daniel 2: The Statue and Imperial Continuity

In the Conjoined Exegesis, Theodoret offers multiple interpretations of Nebuchadnezzar’s statue, including a transposed reading in which Constantine functions as a “second Nebuchadnezzar.” Agyriou notes that this double reading reflects Theodoret’s conviction that imperial forms persist under altered guises.⁵

The Stone “cut without hands” is interpreted Christologically—not merely as an eschatological terminus, but as the Logos intervening within history to undermine imperial absolutism from within (Dan. 2:34–35).

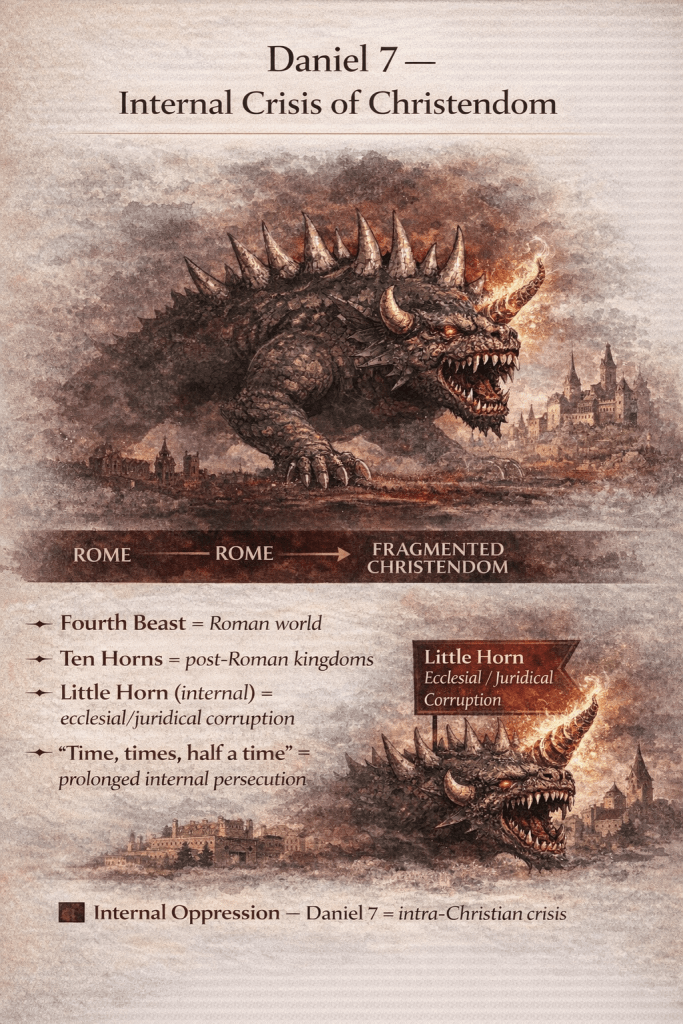

4.2 Daniel 7: The Fourth Beast and the Internal Little Horn

In Les Exégèses, Agyriou explicitly distinguishes Theodoret’s reading of Daniel 7 from his treatment of Daniel 8. In Daniel 7, the Little Horn arises within the Roman beast and therefore signifies internal ecclesial corruption. Agyriou summarizes:

«ἐν τῷ ζʹ κεφαλαίῳ, ἡ μικρὰ κέρας ταυτίζεται μὲ τὴν διεφθαρμένην χριστιανοσύνην.»⁶

This places the Papacy, not Islam, at the center of Daniel 7—aligning Theodoret partially with Christophoros Angelos, though without Angelos’s polemical rigidity.

4.3 Daniel 8: The External Little Horn

Daniel 8, by contrast, concerns an external power that desecrates sacred space. Agyriou notes that Theodoret consistently associates this chapter with Islamic domination, particularly Ottoman power.⁷

This bifurcation—Papacy in Daniel 7, Islam in Daniel 8—is one of the most distinctive features of Theodoret’s system and separates him from Apostolos Makrakis, who tends to merge these roles.

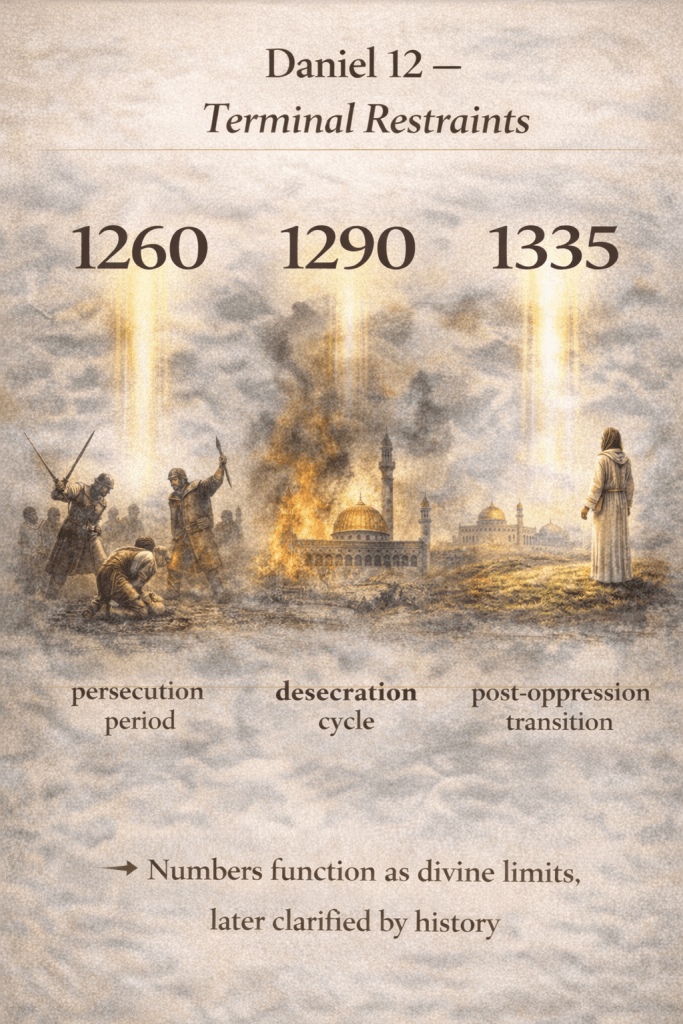

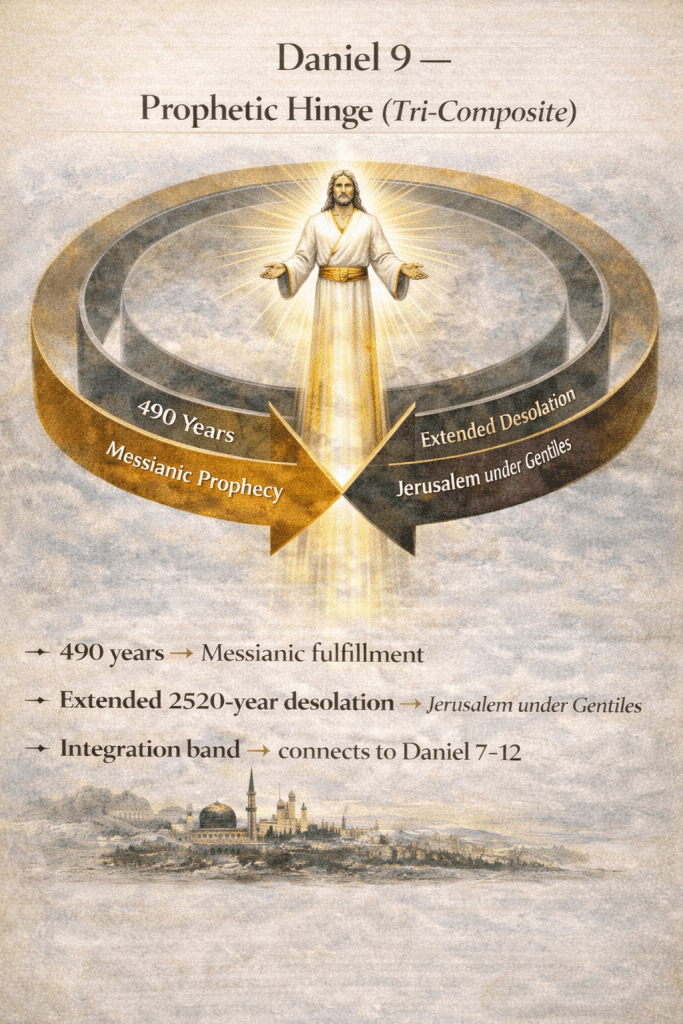

4.4 Daniel 9 and 12: Chronological Restraint

Although the Daniel 9 exposition is lost, Les Exégèses indicates that Theodoret treated the Seventy Weeks as Christologically fulfilled while allowing for post-messianic desolation. Daniel 12’s periods (1260, 1290, 1335) function as divinely imposed limits on oppression rather than as dates for speculative prediction.⁸

Reconstructed Danielic Framework of Theodoret of Ioannina

| Daniel Symbol | Theodoret’s Interpretation (Reconstructed) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Statue (Dan 2) | Succession of world empires culminating in fragmented Christian rule | Emphasis on continuity, not rupture |

| Stone cut without hands | Christ / Logos acting within history | Not postponed to the end |

| Four Beasts (Dan 7) | Pagan Rome → Christianized Rome → fragmented Christendom | Beasts = civilizational systems |

| Ten Horns | Post-Roman political fragmentation | Not individualized rulers |

| Little Horn (Dan 7) | Internal ecclesial–juridical corruption | Intra-Christian crisis |

| Time, times, half a time | Prolonged historical persecution | Symbolic duration, not a date |

| Ram & Goat (Dan 8) | Medo-Persia → Greece | Standard patristic inheritance |

| Little Horn (Dan 8) | External power desecrating sacred space | Identity not named |

| Jerusalem / Temple | Ongoing sacred focal point of history | Not obsolete after 70 AD |

| Daniel 9 (Weeks) | Structural hinge linking Christ and long desolation | No terminal preterist closure |

| Daniel 10–11 | Continuous sacred history guided by angelic powers | Panoramic, not exhausted |

| Daniel 12 (1260 / 1290 / 1335) | Divinely fixed limits clarified by history | No speculative prediction |

Key takeaway: Theodoret works with structures, durations, and patterns, not explicit modern identifications.

5. Comparative Control: Angelos, Gordios, Makrakis

Christophoros Angelos provides the earliest explicit numeric historicism, identifying the Little Horn primarily with Latin apostasy and assigning 1260 years to papal domination.⁹ Gordios systematizes anti-Islamic Danielic polemic but lacks a transfer principle. Makrakis collapses Daniel 7 and 8 into a unified Islamic referent.

Theodoret stands apart by differentiating internal and external enemies and by allowing prophetic roles to migrate historically.

6. Theodoret and Neo-Historicist Daniel Systems

6.1 Convergences

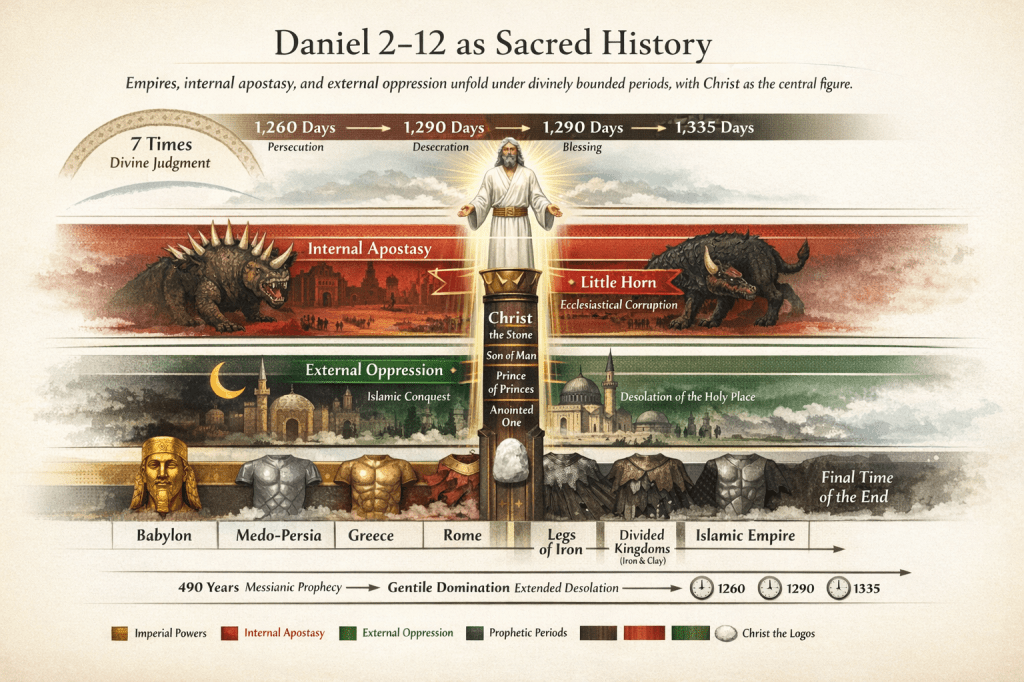

Both Theodoret and modern Neo-Historicist interpretations affirm:

- Daniel as continuous historical prophecy,

- long prophetic periods (1260+),

- Christological fulfillment without preterist closure,

- post-biblical sacred history.

6.2 Divergences

Neo-Historicist systems tend to:

- integrate Daniel 2, 4, 7, 8, 9, 11, and 12 into a single explicit architecture,

- explore extended cycles (e.g., 2520 years),

- apply Danielic structures to later Western revolutionary and post-Christian powers more directly than Theodoret did.

These differences reflect historical context rather than contradiction.

7. Conclusion

The Daniel commentary of Theodoret of Ioannina was not destroyed but displaced through ecclesiastical non-circulation. Its reconstruction reveals a coherent Orthodox historicist system in which Daniel supplies the chronological backbone of sacred history. Restoring this lost commentary clarifies Theodoret’s Apocalypse exegesis and situates him as a pivotal transitional figure between early modern Orthodox historicism and contemporary Eastern Orthoox Historicist interpretations.

Notes (Chicago Style)

- Asterios A. Agyriou, Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse à l’époque turque (1453–1821) (Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies, 1989), 451–452.

- Ibid., 452.

- Ibid., 524.

- Ibid., 524–525.

- Ibid., 522–523.

- Ibid., 518–522.

- Ibid., 517–518.

- Ibid., 519–520.

- Christophoros Angelos, Πόνος… περὶ τῆς Ἀποστασίας (1624), fols. 3r–8v.

Appendix A

Comparative Appendix: Daniel 7–12 in Theodoret of Ioannina and Neo-Historicist Synthesis

A.1 Purpose and Scope of the Appendix

The present appendix offers a comparative outline between the reconstructed Danielic framework of Theodoret of Ioannina and a contemporary Neo-Historicist synthesis of Daniel chapters 7–12. Its purpose is not to retroject modern conclusions into Theodoret’s work, but to clarify how his interpretive architecture anticipates—and in certain respects necessitates—later developments once additional historical data became available.

The comparison is therefore methodological and structural, not anachronistic or speculative.

A.2 Structural Overview: Daniel as a Unified Prophetic System

Both Theodoret and Neo-Historicist interpretation treat Daniel as a single, internally coherent prophetic corpus, rather than as a collection of isolated visions.

| Daniel Chapter | Theodoret (Reconstructed) | Neo-Historicist Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Daniel 7 | Internal ecclesial corruption (Roman/Latin sphere) | Same, extended chronologically |

| Daniel 8 | External imperial oppression (Islamic power) | Same, with long-duration fulfillment |

| Daniel 9 | Christological fulfillment + continued desolation | Tri-composite prophecy (490 + 2520) |

| Daniel 10–11 | Historical warfare of empires | Long panoramic history of Gentile domination |

| Daniel 12 | Fixed divine limits on oppression | 1260 / 1290 / 1335 as terminal markers |

The key difference lies not in what Daniel means, but in how far history is permitted to complete its testimony.

A.3 Daniel 7: The Fourth Beast and the Internal Little Horn

In the reconstructed Daniel commentary, Theodoret interprets Daniel 7 as an intra-Roman and intra-Christian crisis. The Little Horn arises from within the Fourth Beast, altering “times and law” and persecuting the saints through juridical and ecclesial corruption.

Greek Orthodox (Neo) Historicist interpretations retains this identification but extends its chronological horizon, treating the Papal-Latin system not merely as a medieval phenomenon but as a long-duration structural power whose influence mutates rather than disappears.

Continuity:

- Internal origin of the Little Horn

- Ecclesial and juridical character

- Long persecution of the saints

Development:

- Expanded historical span

- Recognition of post-medieval transformations

A.4 Daniel 8: The External Little Horn and Sacred Space

Both Theodoret and Neo-Historicist interpretation identify Daniel 8’s Little Horn with Islamic imperial power, particularly as it desecrates sacred geography and suppresses Orthodox Christian life.

Where Theodoret exercises caution—avoiding explicit terminal dating—the Neo-Historicist synthesis integrates Daniel 8 with:

- Revelation 11–13

- The 1260-year prophetic period

- The collapse of Ottoman political authority

This difference reflects historical restraint, not theological disagreement.

A.5 Daniel 9: From Christological Fulfillment to Tri-Composite Prophecy

Theodoret treats Daniel 9 primarily as a Christological hinge, affirming fulfillment in Christ while allowing for continued desolation and historical struggle. He does not absolutize the Seventy Weeks as an endpoint of sacred history.

Neo-Historicist interpretation builds on this openness by identifying three simultaneous prophetic dimensions within Daniel 9:

- 490 years – Messianic fulfillment in Christ

- 2520 years – “Times of the Gentiles” governing Jerusalem

- Continuity with Daniel 7–12 – Integration into long prophetic cycles

This tri-composite approach does not negate Theodoret’s reading; it formalizes what his method allows but does not systematize.

A.6 Daniel 10–11: Continuous Sacred History

Theodoret’s insistence that prophecy must be read ἐν τῇ ἱστορίᾳ (“within history”) finds its most natural extension in Daniel 10–11. Neo-Historicist interpretation reads these chapters not as second-century vaticinia ex eventu, but as a panoramic historical vision stretching from Persian times through Greco-Roman, Islamic, and modern imperial phases.

Here the methodological kinship is strongest:

Daniel 11 functions as a historical ledger, not an allegory.

A.7 Daniel 12: Terminal Periods and Eschatological Restraint

Theodoret interprets Daniel 12’s periods (1260, 1290, 1335) as divinely imposed limits rather than predictive dates. This caution is understandable given the Patriarchal rejection of his Daniel commentary.

Neo-Historicist synthesis accepts the same numbers but allows history itself to act as interpreter, correlating:

- 1290 years → Temple destruction to Islamic enthronement

- 1335 years → Eschatological transition beyond Ottoman collapse

This represents not a methodological rupture, but a post-Theodoretian completion, made possible by later historical fulfillment.

A.8 Christological Unity: The Pre-Incarnate Logos in Daniel

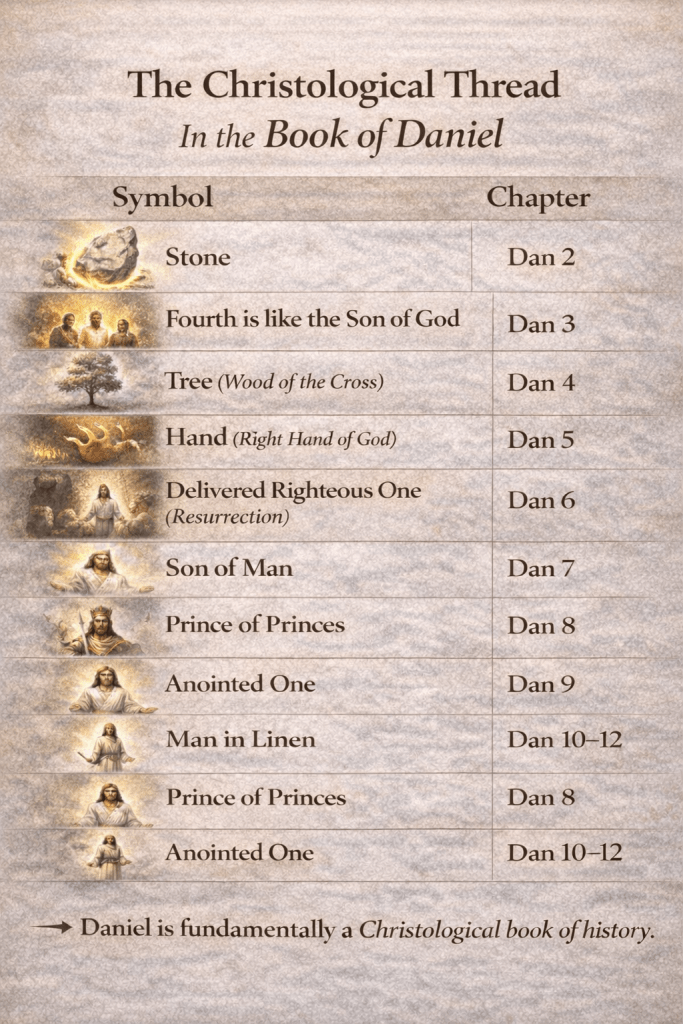

A striking point of convergence is Christology. Both systems recognize that Daniel is saturated with appearances of the pre-incarnate Logos:

- The Stone cut without hands (Dan. 2)

- The Son of Man (Dan. 7)

- The Prince of princes (Dan. 8)

- The Anointed One (Dan. 9)

- The Man clothed in linen (Dan. 10–12)

Neo-Historicist interpretation makes explicit what remains implicit in Theodoret: Daniel is not primarily about Antichrist, but about Christ’s rule within history.

A.9 Conclusion of the Appendix

The reconstructed Daniel commentary of Theodoret of Ioannina and the Neo-Historicist synthesis of Daniel 7–12 stand in a relationship of continuity and completion. Theodoret provides the architectonic insight—Daniel as the chronological skeleton of sacred history—while Greek Neo-Historicism supplies the fully developed historical horizon that Theodoret, constrained by his time, could not yet articulate.

Rather than competing systems, they represent successive stages in a single Orthodox historicist tradition, unfolding as history itself supplies the missing data.

Appendix B

Comparative Appendix: Daniel in Makrakis, Gordios, Angelos, and Theodoret

B.1 Purpose of the Appendix

This appendix situates the reconstructed Daniel commentary of Theodoret of Ioannina within the broader Orthodox historicist tradition, focusing on three major figures frequently cited in Les Exégèses and in modern Neo-Historicist discourse:

- Apostolos Makrakis

- Anastasios Gordios

- Christophoros Angelos

The comparison clarifies points of convergence, divergence, and development, especially regarding the identity of the Little Horn(s), the role of Islam, and the chronological scope of Danielic prophecy.

B.2 Christophoros Angelos: Early Numeric Historicism

Angelos represents the earliest fully explicit Orthodox historicist reading of Daniel among the figures examined.

Key Features

- Identifies Daniel 7’s Little Horn primarily with Latin / Papal apostasy

- Treats Daniel as a continuous prophecy extending into post-Byzantine history

- Explicitly connects Daniel with Revelation using numeric correspondences (1260 years)

- Reads Islamic power largely through Daniel 8, not Daniel 7

Limits

- Strongly polemical and binary

- Less flexible in allowing role transfer between prophetic symbols

- Does not integrate Daniel 9 or 12 into a unified system

Relation to Theodoret

Angelos anticipates Theodoret’s internal vs. external distinction but lacks Theodoret’s methodological caution and allegorical discipline.

B.3 Anastasios Gordios: Anti-Islamic Polemical Daniel

Gordios approaches Daniel primarily through anti-Islamic apologetics, especially in connection with Ottoman domination.

Key Features

- Emphasizes Daniel 8 and the desecration of sacred space

- Identifies Islamic power as a major eschatological adversary

- Draws heavily on patristic and Byzantine precedent

- Reinforces Orthodox collective memory of oppression

Limits

- Minimal engagement with Daniel 7 as an internal ecclesial crisis

- Weak chronological systematization

- Prophecy functions more as moral indictment than temporal structure

Relation to Theodoret

Gordios confirms Theodoret’s reading of Daniel 8 but does not share his dual-axis framework or his interest in prophetic structure.

B.4 Apostolos Makrakis: Maximalist Historicism

Makrakis represents the most expansive Orthodox historicist system, integrating Daniel and Revelation into a single, sweeping narrative of world history.

Key Features

- Identifies Islam and Muhammad as the Little Horn across Daniel 7 and 8

- Collapses internal and external adversaries into a single prophetic antagonist

- Develops an elaborate system of prophetic periods (1260 years)

- Explicitly aligns Daniel’s beasts with successive empires culminating in Islam

Limits

- Over-identification of symbols risks flattening Daniel’s internal distinctions

- Less sensitivity to symbol migration and layered fulfillment

- Polemical intensity sometimes overrides exegetical restraint

Relation to Theodoret

Makrakis extends Theodoret’s historicism but abandons his internal/external bifurcation, producing a more forceful but less nuanced system.

B.5 Theodoret’s Distinctive Contribution

The reconstructed Daniel commentary of Theodoret stands out for three reasons:

- Dual-Axis Prophecy

- Daniel 7 → internal ecclesial corruption

- Daniel 8 → external imperial oppression

- Chronological Sobriety

- Avoids speculative terminal dating

- Treats prophetic periods as limits, not predictions

- Structural Integration

- Daniel as the chronological skeleton

- Revelation as the dramatic unfolding

This combination positions Theodoret as a mediating figure between early Orthodox historicism (Angelos, Gordios) and later maximalist systems (Makrakis).

B.6 Summary Table

| Figure | Daniel 7 | Daniel 8 | Islam | Papacy | Chronology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angelos | Papacy | Islam | Secondary | Primary | Moderate |

| Gordios | Minimal | Islam | Primary | Secondary | Weak |

| Makrakis | Islam | Islam | Primary | Secondary | Strong |

| Theodoret | Internal | External | Major | Major | Restrained |

| Neo-Historicist | Internal | External | Major | Major | Fully integrated |