Islam, the Little Horn, and the Defense of the God-Man in Orthodox Eschatology

By: Jonathan Photius, The NEO-Historicism Research Project

Introduction: Apocalypse as Christological History

Biblical prophecy within the Orthodox tradition has never functioned merely as a speculative forecast of future events. Rather, it has served as theological history: an inspired interpretation of how divine truth—above all the truth of Christ—unfolds, is contested, and is vindicated within time. When read through this lens, the apocalyptic visions of Scripture reveal not a disconnected series of end-time calamities, but a coherent drama centered on the identity of Christ Himself.

Read together, Daniel 7, Revelation 11, and Revelation 20 form a single Christological arc. They describe a prolonged historical trial in which the confession that Jesus Christ is both fully God and fully Man is challenged, suppressed, defended, and ultimately vindicated. This trial is not abstract. It unfolds concretely in history through persecution, doctrinal struggle, and conciliar judgment. Within this framework, the Orthodox identification of Islam and Mohammed with the “Little Horn”—first articulated by Patriarch Sophronius of Jerusalem—emerges not as polemical excess, but as a precise theological judgment grounded in Scripture, history, and dogma.¹

Daniel 7: Authority Grounded in the Incarnation

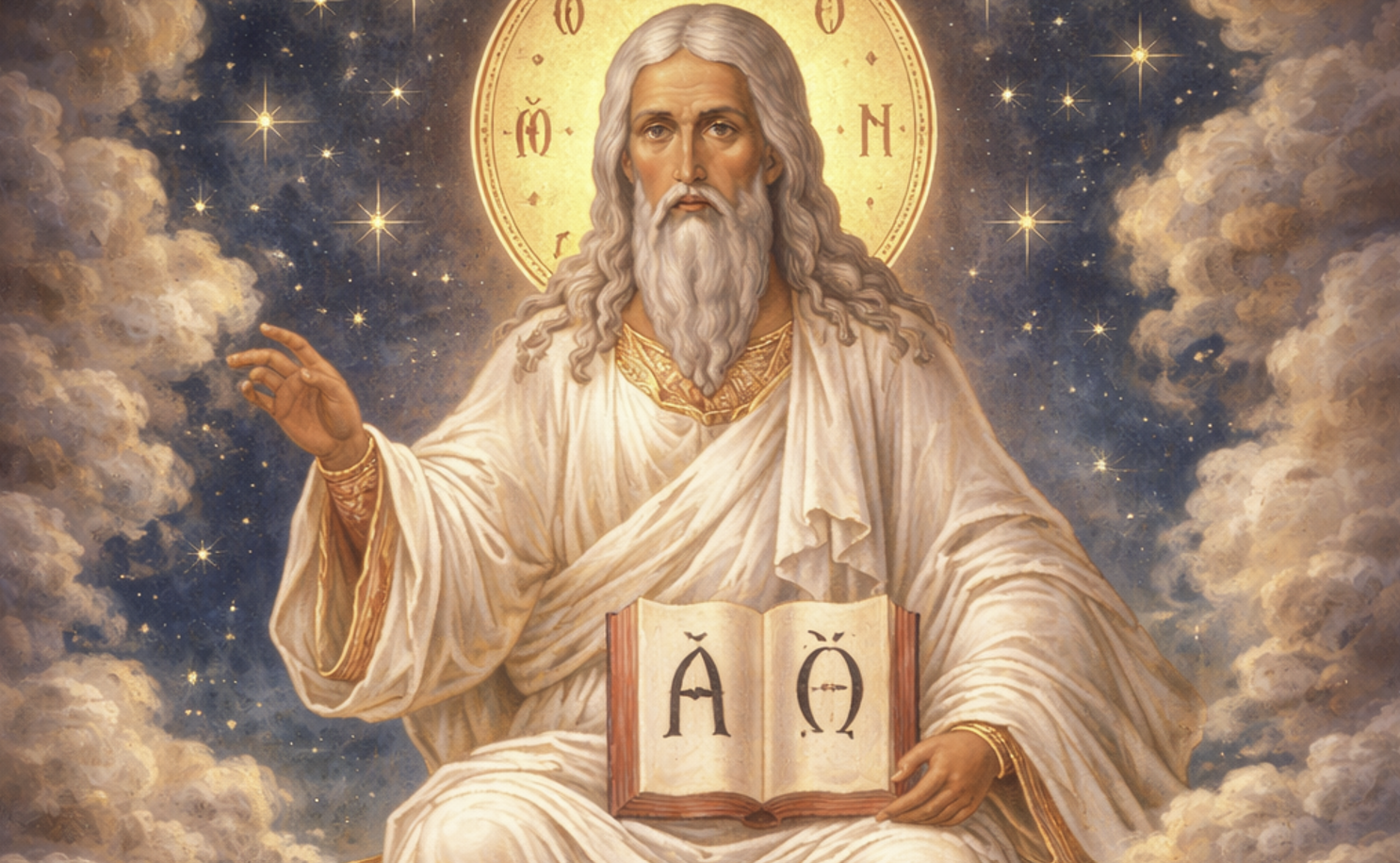

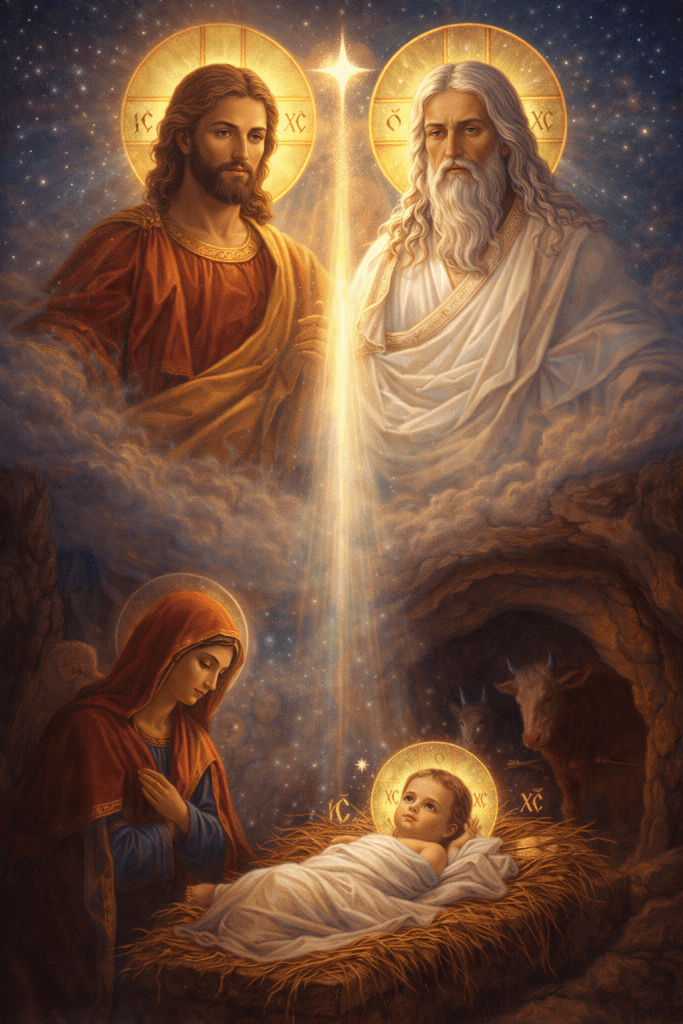

Daniel 7 presents a vision that is frequently reduced to a schema of successive empires. Yet in patristic interpretation its true center lies elsewhere. The vision culminates in the appearance of two figures: the Ancient of Days and one “like a Son of Man.” The Son of Man approaches the Ancient of Days and receives dominion, glory, and a kingdom that shall not pass away (Dan. 7:13–14).

This approach is decisive. Authority is granted not to a purely heavenly abstraction, nor to a merely human ruler, but to the Son of Man precisely because He is united to the Divine. Patristic exegesis consistently understood this moment as a prophetic anticipation of the Incarnation: the Word made flesh, humanity taken into divine life.² The kingdom of Christ is thus grounded ontologically in the union of divine and human natures. In the writings of the Fathers:

- “The Ancient of Days became an infant.” – St. Athanasius of Alexandria. (Homily on the Birth of Christ).

- “But what can I say? For the wonder astounds me. The Ancient of Days Who sits upon a high and exalted throne is laid in a manger.” – St. John Chrysostom (Homily on the Saviour’s Birth).

- “Let the earth bow down, let every tongue sing, chant, and glorify the Child God, forty-day old and pre-eternal, the small Child and Ancient of Days, the suckling Child and Creator of the ages.” – St. Cyril of Jerusalem (Homily on the Presentation of the Lord)

- “The just Symeon received into his aged arms the Ancient of Days under the form of infancy, and, therefore, blessed God, saying, ‘Now lettest Thy servant depart in peace…’” – St. Methodius of Olympus (P.G.18, 3658)

The image depicts the Son of Man approaching the Ancient of Days (Daniel 7), not as a second deity but as the eternal Logos revealed in vision. The identical facial features, cruciform halos, and single descending ray of glory identify the Ancient of Days, the Son of Man, and the Christ Child as one and the same Person: Jesus Christ. The vertical axis visually proclaims the Orthodox confession that the One who receives dominion in heaven is the very One born of the Virgin in humility.

Opposed to this Christological authority stands the Little Horn. Unlike earlier beasts, it does not merely conquer; it “speaks words against the Most High” and “wears out the saints” (Dan. 7:25) by changing the “times and the law” with a new scripture to replace the New Testament, and altered calendar chronology where the years are no longer measured not from Christ but reset and now measured from the Little Horn’s arrival. The conflict is therefore both theological and historical. The saints are persecuted not arbitrarily, but because they confess the true identity of the Son of Man.

Patriarch Sophronius and the Little Horn as a Christological Power

The seventh century witnessed a historical development that brought Daniel 7 into sharp focus: the rise of Islam. Living through the Islamic conquest of Jerusalem, Patriarch Sophronius was among the first Orthodox hierarchs to recognize that this movement constituted a fundamentally Christological challenge, not merely a political catastrophe.³

Islam does not deny Jesus outright. Rather, through the Qur’an it systematically redefines Him: denying His divinity, denying the Incarnation, denying the Cross and Resurrection, and rejecting the Gospel as divine revelation.⁴ In place of the New Testament, Islam offers a rival scripture and a rival account of Christ. In this sense, it “speaks great words against the Most High” while acknowledging Christ only as a prophet.

This makes the identification of Islam and Mohammed with the Little Horn uniquely precise. The persecution of Christians under Islamic rule—particularly those who refused to abandon the confession of the Incarnation and the veneration of icons—flows directly from this theological denial. Sophronius’s insight would later be echoed throughout Byzantine and post-Byzantine Orthodox historicist exegesis.⁵

Revelation 11: Daniel 7 Recast in Ecclesial History

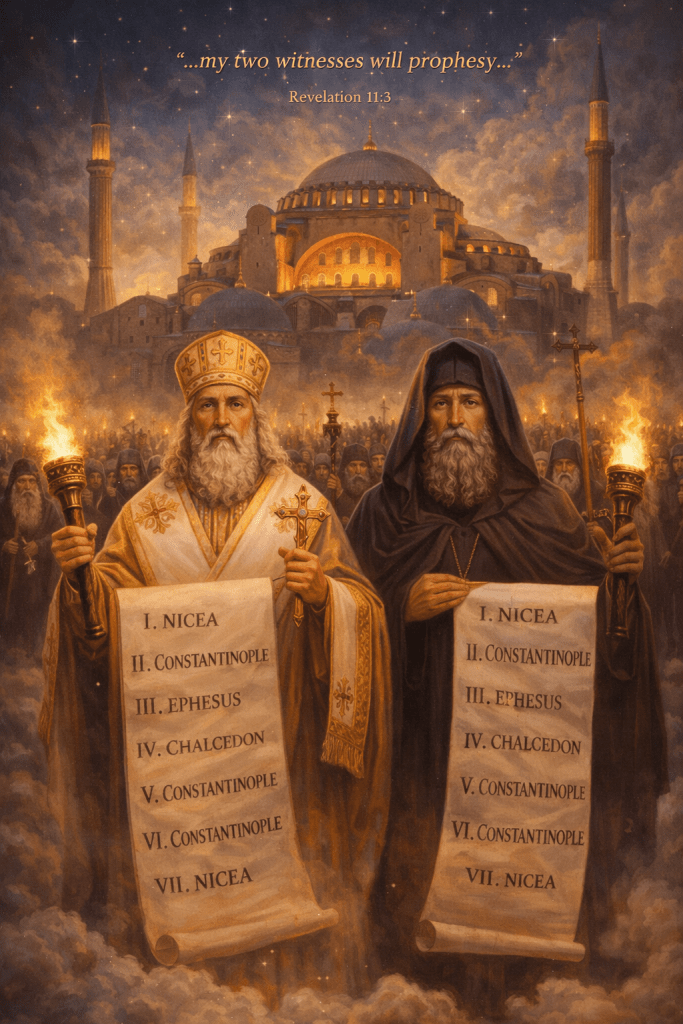

Revelation 11 re-presents the drama of Daniel 7 within the lived experience of the Church. The Two Witnesses testify for 1,260 days, a period corresponding exactly to Daniel’s “time, times, and half a time.” This parallel is neither incidental nor symbolic excess; it signals continuity of meaning.⁶

Within Eastern Orthodox Historicist interpretation, the Two Witnesses represent the Church’s twofold mode of Christological testimony: conciliar and hierarchical authority, embodied in bishops and councils, and ascetical and prophetic authority, embodied in monastics, confessors, and martyrs. Clothed in sackcloth, they signify repentance, suffering, and fidelity rather than political triumph. Fire proceeded from their mouth to devour the heresy of their enemies within that city known as the “Great City”, the Megalopolis, and Queen of Cites, where many of the Ecumenical Councils were held.

In the Eastern Orthodox Historicism reading, the Two Witnesses of Revelation 11 are not isolated end-time figures of Moses and Elijah but the enduring, embodied testimony of the Orthodox Church: the episcopate guarding doctrine and the monastic witness preserving ascetic truth. Both historically are seen clothed in black sackloth garments. Their prophecy unfolds through the Ecumenical Councils, especially those convened in the ‘Great City’ of Constantinople, where the Church bore witness to the full divinity and humanity of Christ against sustained historical opposition.

These Ecumenical Councils were convened within the Great City of Constantinople itself, often in imperial or patriarchal complexes:

- Second Ecumenical Council (381) – Constantinople

Defined Nicene Trinitarian orthodoxy; condemned Pneumatomachianism. - Fifth Ecumenical Council (553) – Constantinople

Addressed the Three Chapters controversy; reaffirmed Chalcedon. - Sixth Ecumenical Council (680–681) – Constantinople

Condemned Monothelitism; affirmed dyothelitism (two wills of Christ). - Seventh Ecumenical Council (787) – initially convened in Constantinople

Interrupted by iconoclast soldiers, then transferred to Nicaea.

Three councils fully held in Constantinople, with the Seventh beginning there.

The remaining councils were held in Constantinople’s immediate conciliar orbit, these locations were imperial suburbs or neighboring cities, tightly integrated into Constantinople’s ecclesiastical and political world:

- First Ecumenical Council (325) – Nicaea

~55 miles (88 km) from Constantinople by land/sea

Defined Nicene Christology (“of one essence with the Father”). - Fourth Ecumenical Council (451) – Chalcedon

Literally across the Bosporus from Constantinople

Defined the hypostatic union (one Person, two natures). - Seventh Ecumenical Council (787) – reconvened at Nicaea

Restored icon veneration.

Two councils held within immediate proximity, effectively part of Constantinople’s conciliar sphere.

The nature of the testimony regarding the “birth of the man-child” through the “seven thunders” is perfectly summed up by the Statement of Chalcedon with respect to the Son of Man and Ancient of Days of Daniel 7:

“Following, then, the holy Fathers, we all unanimously teach that our Lord Jesus Christ is to us One and the same Son, the Self-same Perfect in Godhead, the Self-same Perfect in Manhood; truly God and truly Man; the Self-same of a rational soul and body; co-essential with the Father according to the Godhead, the Self-same co-essential with us according to the Manhood; like us in all things, sin apart; before the ages begotten of the Father as to the Godhead, but in the last days, the Self-same, for us and for our salvation (born) of Mary the Virgin Theotokos as to the Manhood; One and the Same Christ, Son, Lord, Only-begotten; acknowledged in Two Natures unconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably; the difference of the Natures being in no way removed because of the Union, but rather the properties of each Nature being preserved, and (both) concurring into One Person and One Hypostasis; not as though He was parted or divided into Two Persons, but One and the Self-same Son and Only-begotten God, Word, Lord, Jesus Christ; even as from the beginning the prophets have taught concerning Him, and as the Lord Jesus Christ Himself hath taught us, and as the Symbol of the Fathers hath handed down to us.”

- Revelation 12:11 – The faithful overcome by the blood of the Lamb and by the word of their testimony

- Revelation 6:9 – Souls slain for the word of God and for the testimony which they held

- Revelation 11:7 – The beast makes war on the two witnesses when they have finished their testimony

- Revelation 12:17 – The dragon makes war on those who keep the commandments of God and have the testimony of Jesus Christ

- Revelation 19:10 – The testimony of Jesus is the spirit of prophecy

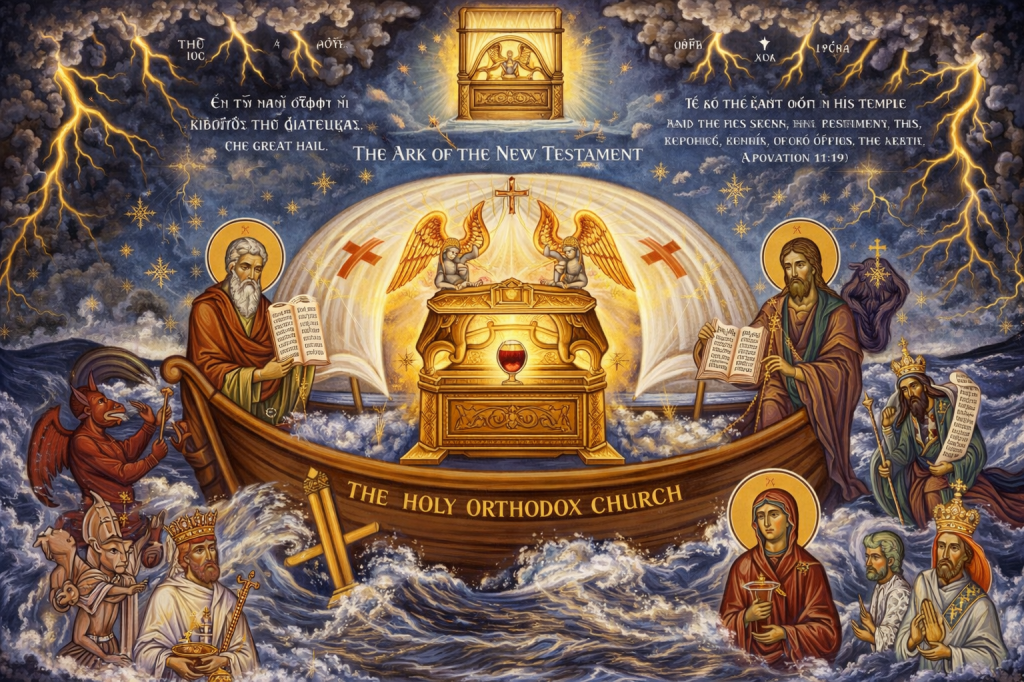

After finishing their testimony, the death of the two witnesses at the hands of the Beast does not signify annihilation, but suppression—the silencing of Orthodox Christological witness under Islamic domination and iconoclastic pressure. From the church’s birth at Pentecost 1260 years would pass where the witnesses would complete their testimony after which Osman 1 and the Ottomans would rise to challenge and dismember the Eastern Roman Empire until its fall in 1453 AD. Babylon is fallen! And the city known as the New Jerusalem where the church of the Holy Wisdom, dedicated to the Logos Jesus Christ became crucified as a mosque, as the Greeks, just like the Israelites in Egypt, were under slavery and domination for a period of 400 years. Yet Scripture records that after “three and a half days,” the breath of life enters them and they stand again. When this occurs, “great fear fell upon those who saw them” (Rev. 11:11).

In Orthodox liturgical language, this fear is not terror but φόβος Θεοῦ, the reverent awe that precedes repentance and communion. The Divine Liturgy itself exhorts the faithful: “With fear of God, with faith and love, draw near.”⁷ The resurrection of the witnesses thus corresponds to conversion, regrafting, and sacramental return.

What follows is a “great earthquake.” Earthquakes in Revelation signify moral and social upheavals, not geological phenomena.⁸ The collapse of false religious authority is accompanied by thunderings (for thunder see: John 12:29) and the revelation of the Ark of the Testament—symbolizing the Church publicly manifested as the true bearer of the New Covenant Testimony of Jesus which the decendents held firmly to, despite of the flood of heresies spewed for from the enraged dragon. The Ark of the Testament held steadfast to the Seven Thunders. The Rudder. This Ark is non other than the Church of the Seven Ecumenical Councils who safeguarded the testimony of the birth of the man-child (Rev 12) throught this period of tribulation history known as the 1260 “days”.⁹ But as this Ark becomes visible after the resurrection of the two witnesses, an eighth and final thunder is heard as the lightening comes from the East to the West. (Math. 24:27).

Revelation 20: Judgment and the Vindication of the Saints

Revelation 20 does not introduce a new eschatological scenario. It delivers the verdict of the Christological trial already described. Thrones appear, judgment is given, and those “beheaded for the testimony of Jesus” are seen reigning with Christ (Rev. 20:4).

This scene corresponds directly to Daniel 7:26–27, where the court sits in judgment and dominion is transferred to the saints of the Most High. Byzantine commentators consistently understood this transfer as ecclesial and theological rather than carnal or political.¹⁰

Within The Eastern Orthodox Historicist interpretations, the “First Resurrection” denotes the vindication of Christological Orthodoxy in history: the restoration of ecclesial authority, the triumph of the Incarnational confession, and participation in Christ’s reign through truth. Universal bodily resurrection and final judgment appear later in Revelation 20:11–15, in full harmony with the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed.¹¹

Scripture Against Scripture: Gospel and Qur’an

Seen in this light, the conflict described in Daniel and Revelation is ultimately a conflict of Scriptures. On one side stands the New Testament, proclaiming the Word made flesh, crucified and risen. On the other stands the Qur’an, redefining Christ and displacing the Gospel. The Apocalypse narrates this conflict not as a geopolitical struggle, but as the central theological drama of post-biblical history.¹²

Conclusion: Conciliar Eschatology, Not Chiliasm

This reading of Daniel 7, Revelation 11, and Revelation 20 does not constitute chiliasm. It proposes no carnal millennium, no replacement of the eschaton, and no second coming before the Second Coming. Instead, it articulates what may rightly be called conciliar eschatology: the historical vindication of the Church’s Christological confession, forged in persecution, defined by councils, and revealed in time.¹³

From Daniel’s vision of the Son of Man, through the testimony of the Two Witnesses, to the thrones of Revelation 20, Scripture proclaims a single truth: the kingdom belongs to Christ because He is one with the Ancient of Days—and to those who confess Him as such.

Footnotes

- Andrew of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse, prologue; John Behr, The Mystery of Christ: Life in Death (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2006), 83–92.

- Cyril of Alexandria, Commentary on Daniel, fragments in PG 71; Aloys Grillmeier, Christ in Christian Tradition, vol. 1 (London: Mowbray, 1975), 70–76.

- Sophronius of Jerusalem, Epistola Synodica, PG 87.3:3197–3208.

- Sidney H. Griffith, The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 47–72.

- Asterios Argyriou, Les exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse (Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies, 1982), 431–445.

- Andrew of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse, on Rev. 11:2–3.

- Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, Communion exhortation.

- Apostolos Makrakis, Interpretation of the Apocalypse (Athens, 1904), on Rev. 6 and Rev. 11.

- Andrew of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse, on Rev. 11:19; Georges Florovsky, Bible, Church, Tradition (Belmont, MA: Nordland, 1972), 43–51.

- Arethas of Caesarea, Scholia on the Apocalypse, PG 106:493–500.

- Metropolitan Hilarion (Alfeyev), Christ the Conqueror of Hell (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2009), 181–189.

- Francis X. Gumerlock, “Chiliasm and the Early Church,” Fides et Historia 45, no. 2 (2013): 7–35.

- John Zizioulas, Being as Communion (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1985), 219–226.

© 2025, Jonathan Photius – NEO-Historicism Research Project