By: Jonathan Photius, NEO-Historicism Research Project

Abstract

The seventeenth century marks one of the richest periods of Orthodox intellectual production under Ottoman rule. Among the most striking examples of this theological renaissance is the Exegesis of the Apocalypse of Georgios Koressios (Γεώργιος Κορέσιος) (c. 1570–after 1654), a work that combines extraordinary erudition with a complex synthesis of patristic theology, natural philosophy, linguistic scholarship, and anti-heretical polemic. Written for an educated Greek readership and widely circulated in manuscript form, Koressios’ commentary represents the most systematic and intellectually ambitious post-Byzantine interpretation of the Apocalypse.

Although situated chronologically in the early modern world, Koressios’ mind and methods remain deeply rooted in the Byzantine scholastic tradition. His Exegesis not only preserves older interpretive lines (Andrew of Caesarea, Arethas, Oecumenius) but reshapes them through the theological controversies of his own time—particularly debates with Roman Catholics, Lutherans, and Calvinists, and the lived reality of the Church under Islamic rule.

This article examines the life, intellectual formation, and apocalyptic theology of Koressios, focusing on his Exegesis of the Apocalypse as preserved and analyzed in Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse à l’époque turque (1453–1821). This study situates Koressios within the Orthodox intellectual landscape and Eastern Orthodox historicist tradition, and evaluates his contribution to the development of modern Greek apocalyptic thought.. It analyzes his interpretive method, and evaluates his treatment of key apocalyptic symbols—especially the Antichrist, the two Beasts, Islam, Babylon, Gog and Magog, and the number 666. It argues that Koressios represents the most systematic and erudite Orthodox apocalyptic theologian of the Ottoman period and that his work forms a crucial bridge between Byzantine patristic exegesis and later Greek historicist commentators.

I. Life and Intellectual Formation

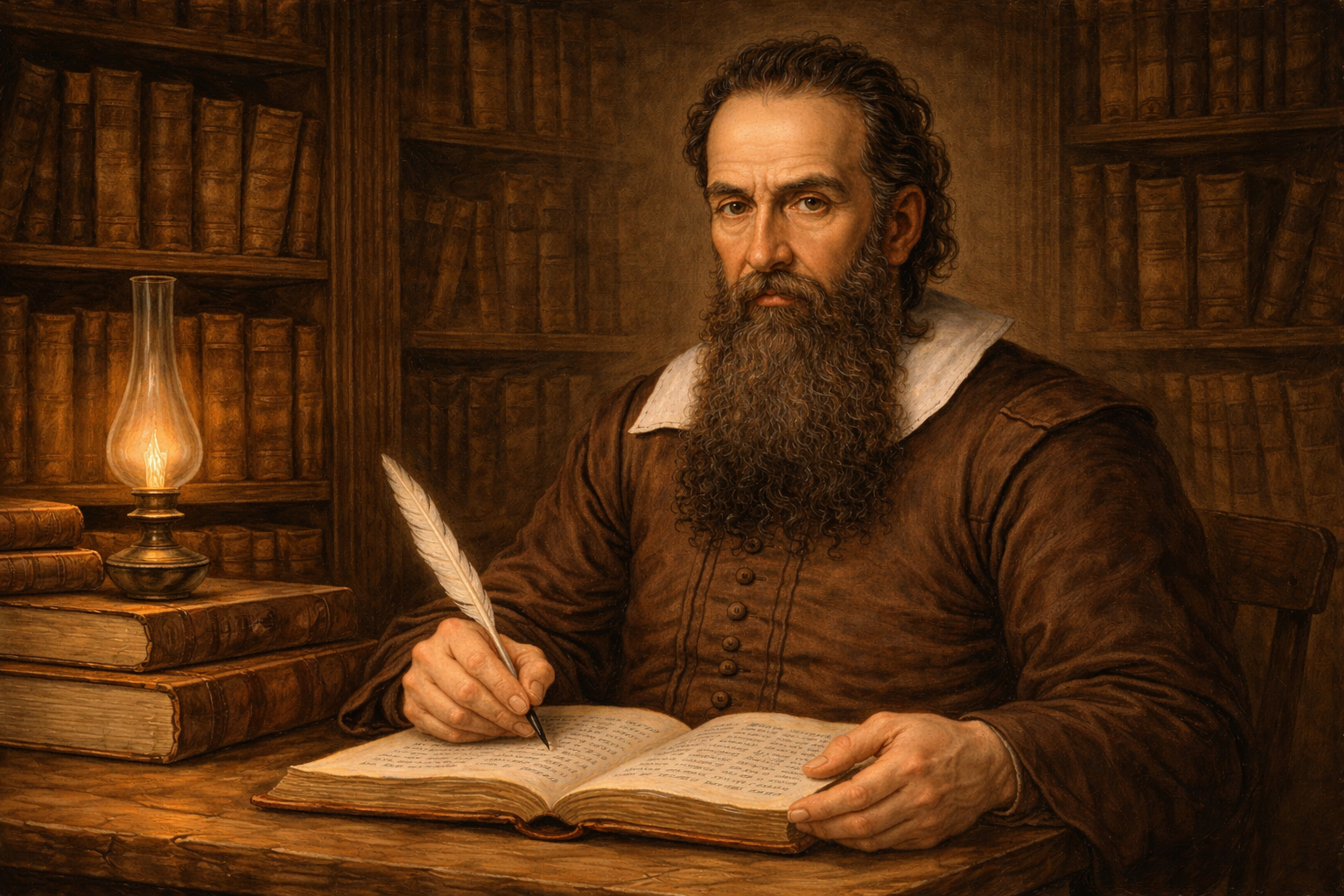

Georgios Koressios was born on the island of Chios around 1570 and died there sometime after 1654, probably around 1660. He belonged to the first generation of post-Byzantine Orthodox intellectuals to receive a full Western university education while remaining theologically uncompromisingly Orthodox. By the early seventeenth century he had studied philosophy and medicine at the University of Padua, then the most important Aristotelian center in Europe. His mastery of classical philosophy, medicine, and natural science would later become a defining feature of his biblical exegesis.¹

Koressios briefly enjoyed academic success in Italy. In 1611 he published in Venice a learned poetic work praising the Medici court, an achievement that likely contributed to his appointment as professor of Greek at Pisa. Yet this Western academic trajectory soon gave way to sustained theological controversy. Koressios emerged as a formidable Orthodox polemicist against Latin, Lutheran, and Calvinist theology, producing an extraordinary number of treatises—many unpublished—on dogmatic, philosophical, and exegetical subjects.² After his sojourn in Italy, Koressios returned to Chios, where he taught until his death at the School of Chios, located in the Monastery of the Holy Anargyroi Kosmas and Damian.

Contemporary Orthodox witnesses regarded him as a major defender of the faith. Patriarch Nektarios of Jerusalem delivered a formal encomium in his honor shortly after his death, and later Greek theologians consistently referred to Koressios as a “doctor of the Orthodox Church.”³ Manuscript evidence indicates that his works circulated widely among educated clergy, though they were never intended for popular devotional use.

Koressios lived and wrote at a time when the Greek Orthodox world was marked by three key conditions:

- Theological competition with Latin, Lutheran, and Reformed theologians.

- Political domination under Ottoman Islam.

- Cultural anxiety regarding identity, continuity, and eschatology.

His Exegesis must therefore be understood as both an intellectual monument and a pastoral intervention. It is shaped as much by scholastic rigor as by the religious psychology of a subjugated people seeking meaning in Scripture.

Koressios’ readership consisted primarily of educated clergy and scholars rather than the general populace. This distinguishes him from more popular apocalyptic writers such as Zacharias Gerganos. The sophistication of his work—its citations from Aristotle, Galen, Dioscorides, Pliny, Thucydides, Virgil, Ovid, and countless patristic authors—reveals a theological mind trained in both classical and Byzantine methods.

II. The Exegesis of the Apocalypse: Scope and Method

Koressios’s Exegesis of the Apocalypse was composed in Chios after 1631, probably around 1640. Written in a learned but clear koine Greek, it is a work of erudition rather than pastoral exhortation. Unlike popular apocalyptic texts of the period, it presupposes a readership trained in patristic theology, classical literature, and philosophical reasoning.⁴

Methodologically, Koressios follows a distinctly Byzantine hermeneutical pattern while expanding it with early modern historical awareness. His interpretation operates simultaneously on four levels: literal-historical, allegorical-moral, typological, and anagogical. No single symbol is exhausted by a single referent. The Woman of Revelation 12, for example, may signify the Theotokos, the Church, and the community of the faithful under persecution, depending on the exegetical level under consideration.

Structurally, Koressios divides the Apocalypse into two great historical epochs. Revelation 6–11 corresponds to the age of the Church, characterized by struggle, persecution, and purification. Revelation 12–20 corresponds to the age of the Antichrist, a short but catastrophic final period. This bipartite scheme draws on Andrew of Caesarea and Arethas, yet Koressios explicitly frames it in light of post-Byzantine historical trauma: the Great Schism, the fall of Constantinople, and the rise of Islam.⁵ This binary structure thus forms the backbone of his interpretation. Unlike some contemporaries, he does not attempt to synchronize the Apocalypse with precise historical dates. Instead, he offers a typological-historical framework in which biblical visions correspond to overarching periods of sacred history.

Koressios employs a multi-level hermeneutic:

- Literal (historical events, political powers, earthly geography)

- Allegorical (spiritual states, virtues, vices)

- Typological (biblical correspondences)

- Anagogical (eschatological fulfillment)

Each symbol thus has multiple referents. The Woman of Revelation 12 is at once the Theotokos, the Church, and the community of the faithful in the final tribulation.

III. Historical Schema and Orthodox Historicism

Koressios interprets the “thousand years” of Revelation 20 symbolically rather than literally. Their expiration does not signal an earthly millennium but the gradual erosion of Christian unity and imperial protection. The rise of Islam marks a decisive historical transition, not because Islam itself is the Antichrist, but because it prepares the world for the final deception. In this respect Koressios occupies a distinctive place within Eastern Orthodox historicism: he resists both futurist speculation and chiliastic expectation while maintaining that Revelation unfolds across real historical epochs.⁶

This approach distinguishes him from later Protestant historicists, who often sought precise chronological calculations, and from certain post-Byzantine writers who directly identified Islam with the Antichrist. Koressios instead insists on a final, personal Antichrist whose reign will be brief, human, and climactic.

IV. Koressios’ Multi-Layered Interpretation of Apocalyptic Symbols

1. Persecution, Heresy, and Islam

For Koressios, Church history progresses through successive trials inflicted by:

- Roman emperors

- internal heresies

- the rise of Islam

- the final Antichrist

He follows a long Greek exegetical tradition in interpreting Islam as a divine chastisement permitted for the purification of the faithful. But he differs in placing Islam not as the Antichrist itself, but as the second Beast and the False Prophet (Rev 13; Rev 19:20).

Mahomet is thus the forerunner of the last deceiver.

2. The Dragon, Beasts, and Locusts

Koressios identifies:

- Dragon = the Devil, the Antichrist, heretics, and the Agarins (Muslims).

- First Beast = heresy, tyranny, doctrinal corruption.

- Second Beast = Islam and Mahomet.

- Locusts = heretics whose teachings sting like scorpions.

These identifications depart from Western tradition and remain distinctly Eastern, rooted in polemic against both Latin and Protestant errors.

3. Babylon the Great

Koressios oscillates between three possibilities:

- Rome

- the World (as confusion)

- Jerusalem, which he finally identifies as Babylon during the reign of the Antichrist.

His choice reflects a longstanding Byzantine anxiety: the final apostasy will occur not in a foreign land, but in the Holy City itself.

V. The Antichrist and His Precursors

A central feature of Koressios’s eschatology is his careful distinction between the Antichrist in a strict sense and in a broader sense. Strictly speaking, the Antichrist is a real human being, not a demon, whose reign will last three and a half years, in accordance with 2 Thessalonians 2. He will demand worship, imitate Christ’s miracles, and persecute the saints.⁷

In a broader sense, however, “Antichrist” may designate all forces opposed to Christ throughout history: Satan himself, heretics, apostates, and oppressive powers. Within this broader category Koressios consistently places Islam. Islam is not the Antichrist, but it is his forerunner and instrument. Heresy and Islam together prepare the nations for the final deception.

Koressios articulates a precise and coherent eschatology:

The Personal Antichrist: He will be a real human being, as taught by 2 Thessalonians 2:3. His reign will last only a short time—three and a half years—before the Second Coming.

Precursors of the Antichrist: Two precursors of the Anticrist are the two great forces prepare his arrival:

- Heresy (Latin deviation, Protestant innovations)

- Islam

Both act as historical instruments of Satan.

VI. The Two Beasts of Revelation 13

Koressios’s interpretation of Revelation 13 is among the most distinctive in the Greek tradition. The first Beast rising from the sea represents heresy in its various forms—especially Latin and Protestant deviation—together with tyranny, moral corruption, and demonic influence. The second Beast rising from the earth represents Islam, and its head is Muhammad, whom Koressios explicitly identifies with the False Prophet of Revelation 19.⁸

The two horns of the second Beast signify the Arab and Turkish (Scythian) powers, while the ten horns may signify either vices opposed to the Decalogue or the military forces that will accompany the Antichrist. In the final conflict, the Antichrist will appear near Jerusalem at the head of these armies. This interpretation reflects Byzantine eschatological anxiety regarding Jerusalem as the site of the final apostasy.

VII. The Number 666

Koressios devotes careful attention to the number of the Beast, reviewing earlier interpretations without embracing speculative certainty. He explicitly rejects the widespread identification of 666 with the name “Mahomet,” despite its popularity in post-Byzantine marginal glosses. He also dismisses the name “Titan” and accepts “Lateinos” only with significant qualification.⁹

Ultimately, Koressios favors a symbolic reading. The number 666 signifies imperfection and deceptive imitation: a triple six parodying divine perfection and the Trinitarian fullness. The Antichrist seeks to present himself as creator and savior, imitating God while remaining ontologically incomplete. For Koressios, the moral and spiritual meaning of the number far outweighs any attempt at onomastic decipherment.

Thus, Koressios reviews classical interpretations—Mahomet, Lateinos, Titan—but rejects literalist readings. He emphasizes instead the symbolic meaning of the number: an incomplete imitation of divine perfection.

SUMMARY TABLE

| Eschatological Figure | Koressios’s Interpretation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| First Beast (Rev 13:1–10) | The Latin West / Papal Rome | Based on 666 = Lateinos; follows Irenaeus, Arethas |

| Second Beast (Rev 13:11–18) | Latin ecclesiastical / pseudo-prophetic authority supporting the first beast | Standard Byzantine view of false-prophet-power |

| 666 | ΛΑΤΕΙΝΟΣ (Latin) | Explicitly affirms this interpretation |

| Muhammad | Not Antichrist; pseudo-prophet only in generic sense | Rejects Muhammad = Antichrist |

| Islam / Turks | Gog/Magog typology, not the Beast | Pre-Antichristic actors |

VIII. Babylon, Gog, and Magog

Koressios considers three possible identifications for Babylon the Great: Rome, the world as confusion, and Jerusalem. While acknowledging the antiquity of the Roman interpretation, he ultimately favors identifying Babylon with apostate Jerusalem during the reign of the Antichrist. This choice reflects a deeply Byzantine conviction that the final betrayal will arise from within sacred history rather than from a purely external enemy.¹⁰

Similarly, Koressios interprets Gog and Magog as Muslim peoples who will follow the Antichrist in the final assault against the Church, while identifying Magog more specifically with false prophecy associated with Muhammad. These identifications differ from those of contemporaries such as Zacharias Gerganos and later Pantazes of Larissa, and demonstrate Koressios’s independent synthesis of patristic tradition and historical observation. Koressios’ scheme positions Islamic power as both precursor and executor of end-time judgment.

Thus, drawing from Ezekiel 38–39 and apocalyptic tradition, Koressios identifies:

- Gog = Muslim nations who will follow the Antichrist

- Magog = Mahomet, the false prophet

IX. Theology Embedded in Apocalyptic Exegesis

One of the most striking features of the Exegesis is the extent to which Koressios embeds extended theological treatises within his commentary. He offers a detailed anti-Calvinist doctrine of grace, distinguishing four modes of divine grace and insisting on human cooperation with God. He strongly affirms the real change (μετουσίωσις) of the Eucharist against symbolic interpretations and articulates a two-stage judgment consisting of a partial judgment after death and a final judgment at the Second Coming.¹¹

The Exegesis concludes with a vigorous polemic against the Filioque, which Koressios presents as the theological root of schism, Western deviation, and ultimately the rise of Islam itself. Sacred history, for Koressios, is inseparable from dogmatic fidelity. Koressios argues:

- additions to the Creed are forbidden,

- the Filioque precipitated schism,

- schism opened the way for Islam’s rise,

- Islam’s power weakened the Christian world.

This forms one of his gravest theological accusations and is key to his reading of sacred history.

X. Koressios within the Orthodox Historicist Tradition

Koressios stands at a pivotal point in the development of Eastern Orthodox historicist eschatology. More erudite than popular apocalyptic writers such as Zacharias Gerganos, less chronologically speculative than later figures such as Pantazēs of Larissa, and more systematic than many of his contemporaries, he provides a comprehensive theological architecture for interpreting Revelation as sacred history. His influence is discernible in later Greek commentators and ultimately in the nineteenth-century work of Apostolos Makrakis.

XI. Manuscript Transmission and Reception

The large number of manuscripts indicates broad circulation among educated clergy. Koressios was influential, though not “popular” in the sense of grassroots apocalyptic writing. His impact is felt especially in later intellectual commentaries and in the anti-Latin polemic of posterity.

Although similar in its attention to symbols, Koressios’ Exegesis is more academic than Gerganos’ popular moral treatise. Gordios borrows Koressios’ historical framework but develops a more rigid conception of the Antichrist. Theodoret of Janina attempts to synthesize both.

Yet Koressios remains unique in:

- the breadth of his patristic citations,

- his systematic theological arguments,

- his anti-Latin polemics,

- his integration of natural philosophy into exegesis.

Conclusion

The Exegesis of the Apocalypse of Georgios Koressios is the most intellectually sophisticated Orthodox commentary on Revelation produced under Ottoman rule. Far from being merely a reactionary product of fear under Ottoman domination, it represents a monumental work of Orthodox scholasticism, synthesis of patristic theology, classical learning, and historical consciousness. Koressios offers not only an interpretation of Revelation but a sweeping theological worldview shaped by tradition, reason, and the lived experience of the early modern Greek Church. Koressios offers a vision of history governed by Christological truth rather than chronological speculation, and his work remains foundational for understanding Eastern Orthodox historicism as a distinct eschatological tradition.

Footnotes

- Konstantinos Sathas, Νεοελληνικὴ Φιλολογία (Athens, 1868), 247–250.

- Émile Legrand, Bibliographie hellénique, vol. 3 (Paris, 1895), 262–269.

- A. Papadopoulos-Kerameus, ed., “Ἐγκώμιον εἰς Γεώργιον Κορέσσιον,” ΑΕΕΕ 3 (1889): 521–528.

- Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse à l’époque turque (1453–1821), chap. IV.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- 2 Thessalonians 2:3; Les Exégèses, chap. IV.

- Les Exégèses, chap. IV, on Revelation 13 and 19.

- Ibid., discussion of Revelation 13:18.

- Ibid., section on Babylon the Great.

- Ibid., theological excursuses on grace, Eucharist, and judgment.

FURTHER READING

Octavian-Adrian Negoita, “Georgios Koressios. Exegesis to the Apocalypse of John“, in: M. Frederiks (ed.), Christian-Muslim Relations. Primary Sources, Vol. 2: 1500-1700, London-New York: Bloomsbury, 2023, pp. 58-60

Asterios Argyriou, Les exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse à l’époque turque (1453-1821). Esquisse d’une histoire des courants idéologiques au seindu peuple grec asservi. Thessaloniki, 1982