By Jonathan Photius, NEOhistorcism Research Project

Introduction

The emergence of a fully articulated Eastern Orthodox historicist eschatology did not arise suddenly in the nineteenth century with Apostolos Makrakis, nor was it imported from Protestant interpretations of Daniel and Revelation. Its roots lie earlier, in the crucible of Ottoman persecution, Orthodox exile, and post-Byzantine reflection on history, prophecy, and suffering. Among the earliest and most decisive figures in this development stands Christophoros Angelos (c. 1575–1638), an Orthodox monk, priest, and confessor whose treatise On the Apostasy of the Church and the Antichrist (c. 1624) represents the birth of Greek Orthodox numerical historicism.¹

Angelos is remarkable not only for the boldness of his prophetic interpretations—particularly his application of the 1260-year period to Mohammed and Islam—but also for the existential context from which his theology emerged. His historicism was not speculative or polemical in the abstract; it was forged through imprisonment, torture, refusal to apostatize, and eventual exile. When his biography is read together with his commentary, Angelos emerges as the earliest Orthodox interpreter to unite confessional suffering, chronological prophecy, and ecclesial anti-chiliasm into a single coherent system.

I. Biography: Monk, Priest, Confessor, Exile

Birth and Monastic Identity

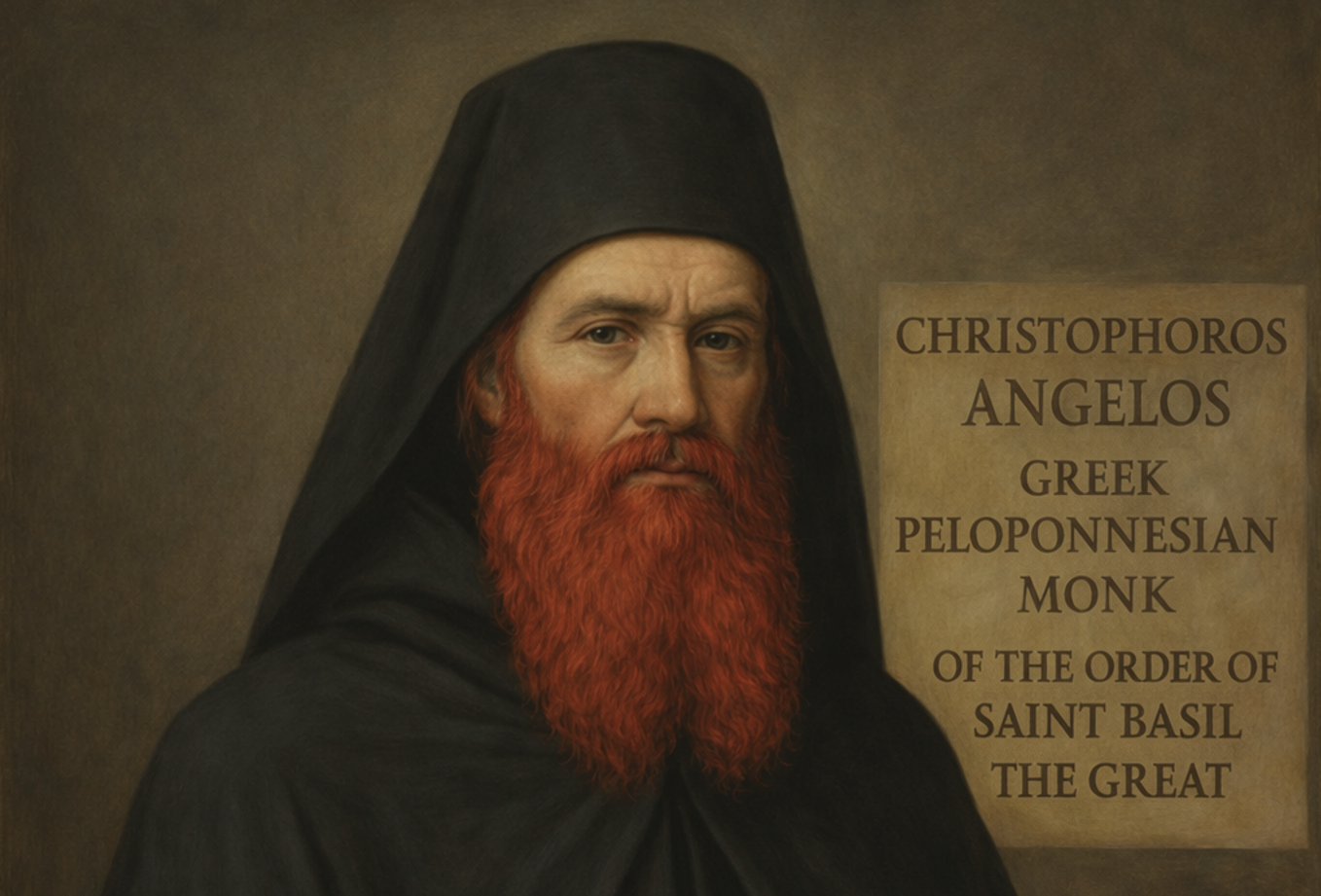

Christophoros Angelos was born around 1575 in Gastrouni, in the Peloponnese of western Greece, under Ottoman rule. He later identified himself explicitly as a monk of the Order of Saint Basil, describing himself in an English manuscript colophon as “a Hellenic Peloponnesian monk of the order of Saint Basil.”² This self-identification decisively establishes Angelos as a monastic cleric rather than a lay intellectual, correcting earlier assumptions in secondary literature.

Ordination, Arrest, and Torture

In 1606, Angelos was ordained in Athens, where his education, monastic status, and unusual appearance—particularly his long red beard—made him conspicuous to Ottoman authorities. He was accused of espionage on behalf of Spain, arrested, and imprisoned. During interrogation, Ottoman judges demanded that he convert to Islam. Angelos refused and endured imprisonment and torture rather than apostasy.³

This experience profoundly shaped his theology. Islam, in his writings, is not an abstract theological adversary but a persecuting power experienced bodily, a tyranny permitted by God yet bounded by divine limits.

Escape and English Exile

Around 1608, Angelos escaped Ottoman captivity and fled to England, where he remained until his death. England provided a rare environment in which an Orthodox monk could write openly about Islam, apostasy, and prophecy without fear of reprisal.⁴ Throughout his exile, Angelos remained firmly Orthodox, continuing to identify himself as Greek, monastic, and ecclesial. He frequently recalled the tortures he endured in Turkish prisons, situating his prophetic interpretations within lived suffering rather than abstract speculation.

Death and Reputation

Christophoros Angelos died on February 1, 1638, at approximately 67 years of age. English sources remembered him as “a pure Greek and an honest man,” a fitting epitaph for a confessor who refused conversion under torture.⁵

II. The Treatise: Title, Date, and Character

Title and Genre

The work examined here is best reconstructed under the title:

Πόνος Χριστοφόρου τοῦ Ἀγγέλου περὶ τῆς ἀποστασίας τῆς Ἐκκλησίας καὶ τοῦ Ἀντιχρίστου

(The Labor of Christophoros Angelos concerning the Apostasy of the Church and the Antichrist)

The term πόνος (“toil,” “labor”) reflects the confessional character of the work: this is theology written after persecution.

The treatise is not a verse-by-verse commentary but a synthetic prophetic exposition, harmonizing Daniel and Revelation through chronological reasoning, theological reflection, and ecclesial concern.

Date of Composition

Internal chronological calculations, combined with manuscript evidence and later bibliographic notices, indicate that the work was composed around 1624, during Angelos’s English exile.⁶ The freedom of exile explains the explicitness of Angelos’s identifications—particularly his treatment of Islam and Mohammed—which could not safely circulate within Ottoman-controlled territories.

III. The Year–Day Principle and Orthodox Historicism

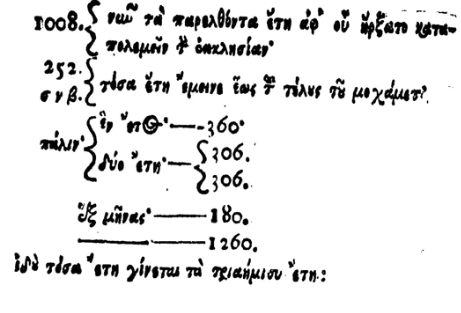

Christophoros Angelos is the first Orthodox writer to employ the year–day principle systematically across Daniel and Revelation. While symbolic understandings of prophetic time existed earlier in Byzantine tradition, Angelos applies numerical conversion consistently and structurally:

- One “time” (καιρός) = 360 years

- “Times” = 720 years

- “Half a time” = 180 years

- Total = 1260 years

These calculations govern his interpretation of Daniel 7, Daniel 12, and Revelation 11–13.⁷

Crucially, Angelos explicitly denies that such calculations permit prediction of the Second Coming. He repeatedly cites Matthew 24 and Acts 1, insisting that the day and hour remain known only to the Father. Chronology reveals the duration of historical trials, not the date of the Parousia.⁸ This insistence places Angelos firmly within Orthodox anti-chiliasm.

IV. The 1260 Years and Islam: A Foundational Innovation

Christophoros Angelos appears to be the earliest known historicist interpreter—Eastern or Western—to apply the Danielic–Johannine 1260-year period explicitly to Mohammed and the Islamic dominion.⁹ Earlier Byzantine authors identified Islam typologically (as Ishmaelites, locusts, or divine chastisement), but Angelos converts this typology into a full chronological historicist system.

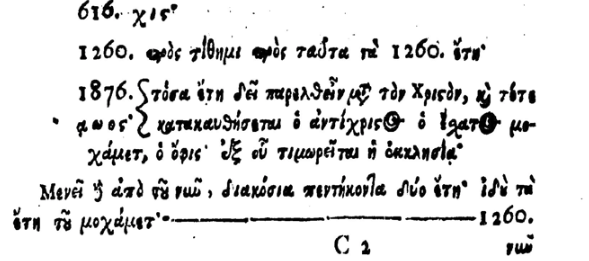

“Concerning the Church: Mohammed began to persecute the Church at the time of the year 616. And for this cause the persecution lasted 150 years. Then the Arabs arose, in the year 623. For to these was given the wing of the serpent, in the tyranny against the Christian fox, into the wilderness. And to the woman was given a time, and times, and half a time, that she should be nourished from the face of the serpent of Mohammed (Revelation 12). And the times were 1260 years, equal to the period of desolation. Mohammed began to afflict the Church in the year 616 of Christ. 616 + 1260 = 1876. Thus the time of Christ is then fulfilled, and then the Antichrist is brought low. For Mohammed, the serpent, is he that afflicts the Church. But from now there remain 252 years, equal to the span from Mohammed — 1260.”

For Angelos, Islam is not merely a scourge but a prophetically measured empire, permitted by God for a finite duration. This interpretation is inseparable from his biography: a monk who refused conversion under torture reads Islam not as an abstraction but as a real power whose dominion must nevertheless end.

Angelos also considers the Papacy the Little Horn of Daniel. From the rise of papal supremacy, Angelos reckons 605 years already elapsed. Adding these to his own present year (1624), he concludes that 1020 years of Antichrist’s reign have already passed. Thus the age of Antichrist is not distant nor future: it is present, already advanced into its thousandth year. The papacy, as the little horn of Daniel, rules in apostasy until Christ comes to destroy it.

Angelos closes out his commentary with the following:

Moreover, the beginning of the desolation which befell the holy Jerusalem is reckoned from the capture of that city and from that seizure which occurred in the year 636, when the Hagarenes took possession of it. And from this beginning until the complete disappearance of their authority, there are reckoned twelve hundred and sixty years—namely, times, and a time, and half a time; that is, either years, or months, or days. And when this is fulfilled, then the so-called dominion of the Hagarenes is brought to an end (…) These periods were explained according to numerical reckoning in the divine and holy Apocalypse, where it says that the woman was given the two wings of the great eagle, so that she might flee into the wilderness, to her own place, where she is nourished for a time, and times, and half a time. Therefore we understand that this signifies one thousand two hundred and sixty years according to this numerical reckoning, for such is the explanation given.And thus it is said that according to Christ, and according to the calculation of one thousand two hundred and sixty years, the end of this period is determined. Yet we have spoken correctly in saying that from the time of Christ until now approximately one thousand two hundred and twenty years have already passed. And in order to show the solution of this matter—lest we ourselves should fall into doubt, even though some of our wise men have spoken otherwise—we have set forth these mysteries of God. The voice of the angel speaks clearly to John in the fourth book; and the Spirit makes it clear that whatever the angel said to Daniel, by his own word, pertains to its own appointed time, an tht the questions are precise. And in time the explanation is revealed, and at the proper season the interpretation is made known, so that it may be understood how the matter will come to pass. For God guides us in truth, and He does not permit the end to become a cause of scandal or disturbance, nor does He allow confusion to arise. But rather, in due time, He reveals the solution, so that we may not fall into error. For it is necessary that those who seek understanding examine these matters carefully according to their proper number and correspondence, and not with rashness or confusion.

This passage is exceptionally important for understanding Christophoros Angelos’ mature historicist framework. First, he explicitly anchors prophetic time in historical calculation, affirming the 1260-year period as a real chronological span, not merely symbolic or indeterminate. He then correlates this span with elapsed history “from the time of Christ until now,” showing an already developed day-year hermeneutic functioning inside Orthodox exegesis.

Second, the ἀπόκρισις (“Response”) section clarifies Angelos’ theology of history: prophetic gifts cease not arbitrarily, but judicially, as a response to ἀνομία (lawlessness). This places Islam within a divine economy of chastisement, not merely as an external political force. The pairing of Ishmael and Mohammed is deliberate and deeply traditional, grounding Islam genealogically and prophetically.

Most striking is the unambiguous identification of Mohammed with Antichristic agency, not as a future individual but as a historical power operating within a defined prophetic timespan. This confirms Angelos as the earliest known Orthodox writer to apply the 1260-year calculation directly to Islam, decades to perhaps two centuries before similar calculations appear in Western historicism.

Finally, the tone is pastoral and penitential rather than speculative: Angelos warns against doubt and insists submission to God’s providential memory (μνήμη τοῦ Θεοῦ). This distinguishes his work from later polemical chronologists and shows that Greek Orthodox historicism was born not in academic abstraction, but in suffering, exile, and confessional witness.

V. Daniel, Revelation, and the Shape of History

Angelos treats Daniel as the interpretive key to Revelation. Daniel provides the temporal framework; Revelation confirms and amplifies it. The Apocalypse is not detached from history but embedded within it.¹⁰

John, in Revelation 13, describes the beast: “And I saw a beast rise up out of the sea, having seven heads and ten horns, and upon his horns ten crowns.” These ten horns signify ten kingdoms, arising from the ruin of the Roman Empire. Angelos identifies these as the dynasties into which Rome was divided after its collapse under the Emperor Phocas (r. 602–610):

- The Scottish dominion.

- The kingdom of the Franks.

- The Visigoths in Spain and Gaul.

- The Ostrogoths.

- The Lombards in Italy.

- The Lombards in Pannonia.

- The Suevi in Galicia.

- The Prussians.

- Another Lombard principality.

- Constantinople.

Thus the prophecy of the ten horns is fulfilled in the dismemberment of Rome into ten successor kingdoms. The beast of Revelation, identified with Antichrist, rules through these powers, crowned with authority after the fall of Rome.

The Ten Horns of the Beast (Revelation 13; Daniel 7:24)

| Angelos (1624) | Typical Protestant Lists (Brightman, Mede, et al.) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Scottish dominion (Σκωτικὴ δυναστεία) | Huns | Angelos adapts to a Western audience, inserting Scotland instead of Huns. |

| 2. Franks (Φραγκικὴ δυναστεία) | Franks | Stable across nearly all lists. |

| 3. Visigoths in Spain & Gaul (Οὐισιγοττικὴ) | Visigoths | Consistent identification. |

| 4. Ostrogoths (Οὐστρογοττικὴ) | Ostrogoths | Same as Protestant tradition. |

| 5. Lombards in Italy (Λογγοβάρδικοι ἐν Ἰταλίᾳ) | Lombards | Commonly included by Protestants. |

| 6. Lombards in Pannonia (Λογγοβάρδικοι ἐν Παννονίᾳ) | Suevi | Angelos distinguishes two Lombard dominions where Protestants often list Suevi. |

| 7. Suevi in Galicia (Σουηβικοί ἐν Γαλλικίᾳ) | Vandals | A difference: Angelos highlights Suevi, while Protestants often cite Vandals. |

| 8. Prussians (Πρωστικὴ δυναστεία) | Burgundians | Prussians are an unusual substitution; Burgundians were standard in Western lists. |

| 9. Another Lombard principality (Λογγοβάρδικοι βʹ) | Heruli / Anglo-Saxons | Angelos repeats Lombards; Protestants include either Heruli or Anglo-Saxons. |

| 10. Constantinople (Κωνσταντινούπολις) | Anglo-Saxons / Greeks | Angelos uniquely keeps Constantinople as one of the horns. Protestants usually count Greeks separately, sometimes England. |

His interpretation of Revelation 20 is explicitly spiritual and ecclesial. The “thousand years” signify the reign of Christ through the Church, not a future earthly kingdom. Satan’s binding indicates restriction, not annihilation; his later release signifies renewed deception prior to final judgment.¹¹ Angelos thus decisively rejects chiliasm, even while employing extensive chronological analysis.

VI. Influence and Legacy

Although later Orthodox historicists do not always cite Angelos explicitly, his influence is unmistakable. His methods and categories reappear—often in moderated form—in Anastasios Gordios, Pantazēs of Larissa, John Lindios of Myra, Kyrillos Lavriotis, Theodoret of Ioannina, and most fully in Apostolos Makrakis. Without Angelos, later Greek Orthodox historicism lacks a coherent numerical prototype.

Modern scholarly confirmation of Angelos’s importance is found in Asterios Agryriou’s Les Exégèses Grecques de l’Apocalypse, the most comprehensive study of post-Byzantine Greek apocalyptic interpretation. Although Agryriou does not fully develop the numerical implications of Angelos’s system, he decisively situates Angelos among the earliest interpreters to move beyond typological readings toward a historical-prophetic synthesis.¹²

Conclusion

Christophoros Angelos must be recognized as an Orthodox confessor who was persecuted by the Turks and the founder of Greek numerical historicism pointing to an Islamic Beast. His treatise represents the earliest systematic Orthodox attempt to interpret Daniel and Revelation as continuous historical prophecy, extending from Late Antiquity into the Christian present. Forged through persecution and exile, Angelos’s historicism transforms suffering into meaning and history into divine pedagogy.

Far from being a marginal figure, Angelos stands at the headwaters of a tradition later refined by Makrakis and others. To understand Orthodox historicism without him is to misunderstand its origin, its courage, and its profoundly pastoral intent.

Notes

- On the early development of Greek Orthodox historicism, see Asterios Agryriou, Les Exégèses Grecques de l’Apocalypse (1453–1821) (Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies, 1988).

- Christophoros Angelos, English manuscript colophon; summarized in Jonathan Photius, “Christophoros Angelos: Treatise on the Apostasy of the Church and the Antichrist,” NeoHistoricism.net, September 14, 2023.

- Photius, “Christophoros Angelos.”

- On England as a refuge for Eastern Christians in the early seventeenth century, see Photius, “Christophoros Angelos.”

- English biographical notices cited in Photius, “Christophoros Angelos.”

- Agryriou, Les Exégèses, section on early seventeenth-century interpreters.

- Angelos, Πόνος περὶ τῆς ἀποστασίας, Daniel and Revelation sections.

- Ibid., explicit citations of Matthew 24 and Acts 1.

- Agryriou, Les Exégèses; Photius, “Christophoros Angelos.”

- Angelos, Πόνος, passim.

- Ibid., Revelation 20 exposition.

- Agryriou, Les Exégèses.

Bibliography

Angelos, Christophoros. Πόνος περὶ τῆς ἀποστασίας τῆς Ἐκκλησίας καὶ τοῦ Ἀντιχρίστου [Treatise on the Apostasy of the Church and the Antichrist]. Composed ca. 1624. Greek manuscript tradition; written during Angelos’s exile in England. Critical English translation and analysis by Jonathan Photius (Neo-Historicism Project).

Agryriou, Asterios (Asteriou). Les Exégèses Grecques de l’Apocalypse (1453–1821): Esquisse d’une Histoire des Courants Interprétatifs. Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies, 1988.

Photius, Jonathan. “Christophoros Angelos: Treatise on the Apostasy of the Church and the Antichrist.” NeoHistoricism.net, September 14, 2023.

https://neohistoricism.net/2023/09/14/christophoros-angelos-treatise-on-the-apostasy-church-antichrist/

© 2025, Jonathan Photius – NEO-Historicism Research Project