Introduction

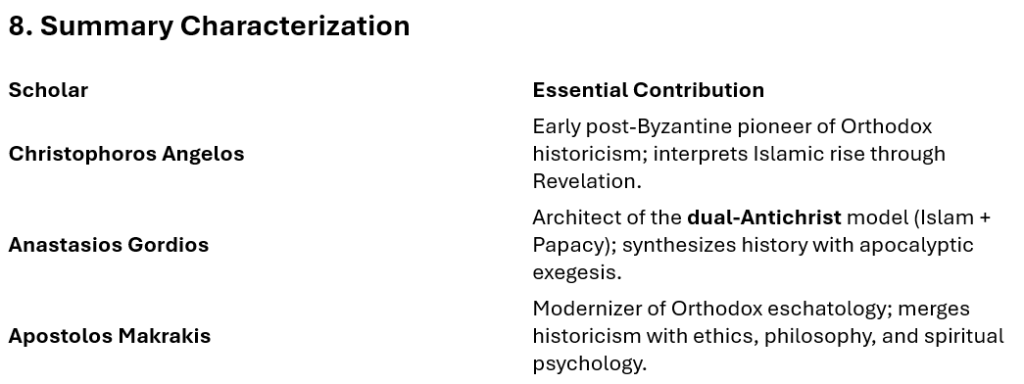

Anastasios Gordios (c. 1654–1729) occupies a uniquely influential position in the development of post-Byzantine Orthodox eschatology. His Treatise on Mahomet and Against the Latins (1717) constitutes not only a vigorous polemical intervention but also the most systematic articulation of the historicist method within early modern Greek theological thought. Building on patristic commentaries, Byzantine apocalyptic traditions, and contemporary political experience under Ottoman rule, Gordios forged a comprehensive interpretive framework that shaped the Orthodox imagination for more than a century.

I. Intellectual Background and Historical Setting

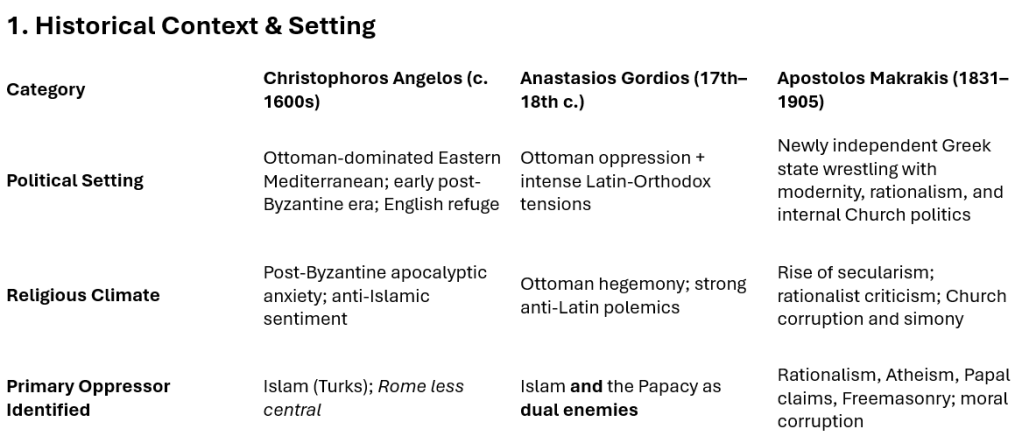

Gordios wrote in an era marked by political subjugation and confessional anxiety. The fall of Constantinople (1453), the gradual Islamization of former Byzantine territories, and the aggressive missionary activities of Latin clergy created a threefold crisis—political, ecclesiastical, and cultural—that demanded theological interpretation. Earlier writers, such as Christophoros Angelos, had already begun to read the rise of Islam through a historicist lens, identifying Ottoman domination with the prophetic imagery of Revelation.¹ Gordios developed this tendency into a fully integrated theological system.

Unlike his predecessors, Gordios synthesized a vast range of materials: Byzantine chronicles; patristic commentaries on the Apocalypse (especially Andrew and Arethas of Caesarea); polemical literature against Islam and the Latin Church; and the post-Byzantine exegetical works of Maximos the Peloponnesian and Zacharias Gerganos.² This synthesis allowed him to treat the Apocalypse not as a symbolic or future-oriented book, but as a divinely encoded interpretation of world history culminating in the circumstances of his own era.

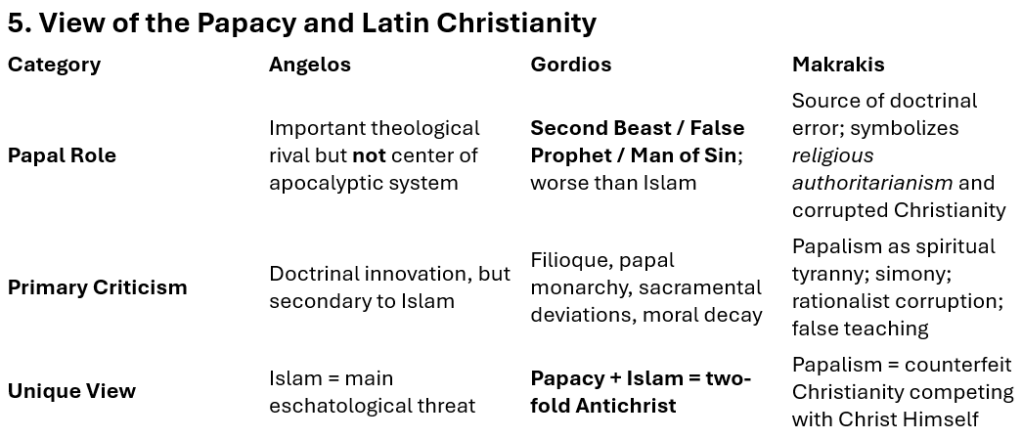

II. The Dual Antichrist: Islam and the Papacy

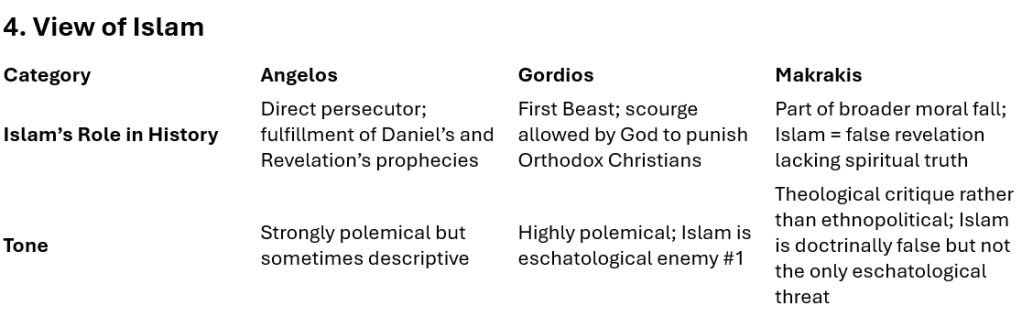

Gordios’s most significant contribution to Orthodox historicism is his elaboration of the “dual Antichrist” concept. Building on the patristic identification of Lateinos (Λατεῖνος) with the number 666 and on long-standing interpretations of Islam as a demonic scourge, Gordios argues that the Apocalypse’s two Beasts represent two historical powers:

- Islam/Mahomet, the first Beast rising from the sea (Rev. 13:1–10);

- The Papacy, the second Beast or “False Prophet” rising from the earth (Rev. 13:11–18).³

This bifurcation allowed Gordios to integrate two longstanding enemies of Orthodoxy—Ottoman political domination and Latin ecclesiastical claims—into a unified eschatological framework. For Gordios, the Papacy poses a greater danger than Islam, because its deception is spiritual, not merely political.⁴ Islam persecutes the body; the papacy, through doctrinal corruption and pretensions to divine authority, threatens the soul. The convergence of these two forces constitutes, for Gordios, the full manifestation of Antichrist in history.

III. Historicism as Hermeneutic and Pastoral Strategy

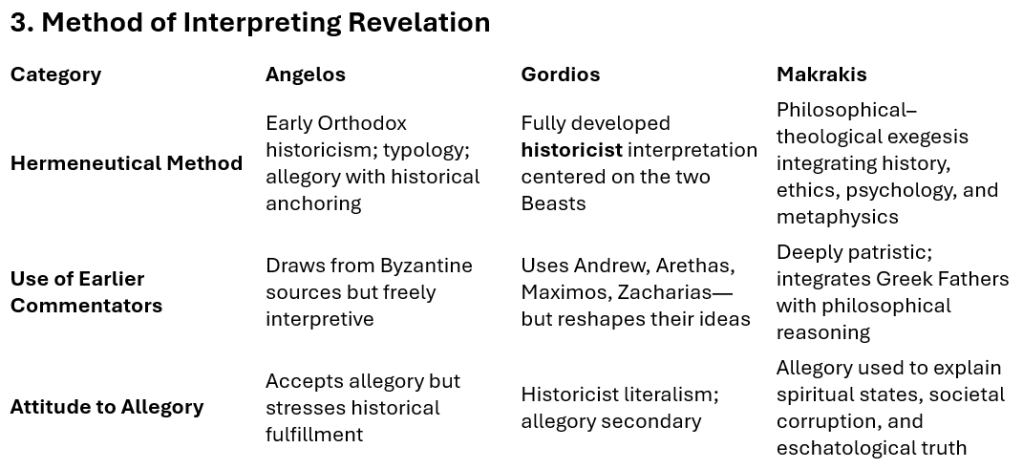

Gordios’s exegesis is fundamentally historicist. He reads the symbolic figures, visions, and catastrophes of Revelation as keys to interpreting successive world epochs and, more importantly, the sufferings of the Orthodox Church under Ottoman and Latin pressure. Chapters XII and XIII of Revelation—describing the Dragon, the Woman, and the two Beasts—form the backbone of his entire exegetical project.⁵

The historical fall of the Eastern patriarchates becomes, in Gordios’s reading, the direct fulfillment of the Dragon’s war against the Woman (Rev. 12). The “desert” prepared by God for the Woman is identified with Russia, a providential refuge for Orthodoxy.⁶ The 1260 days of the Woman’s sojourn correspond to the duration of Islamic domination, interpreted as approximately 1260 years—a scheme shared with earlier interpreters such as Christophoros Angelos and later developed by Apostolos Makrakis.

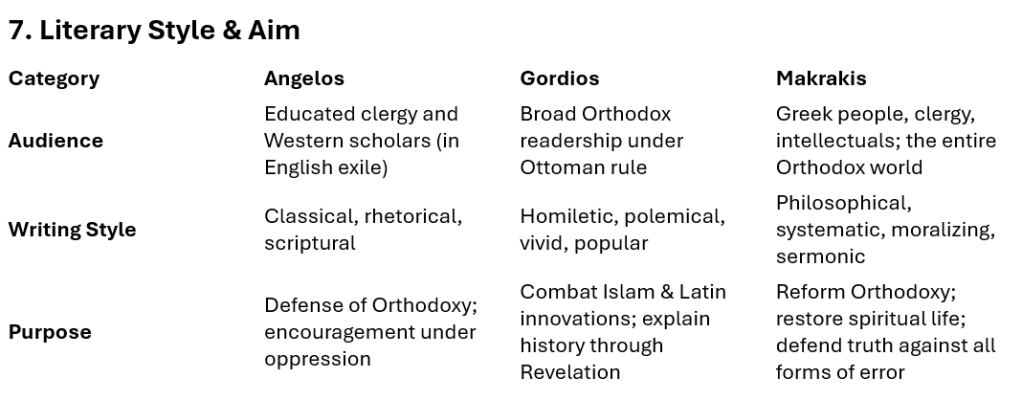

Gordios’s exegesis functions not merely as a scholarly commentary but as a pastoral exhortation. By framing contemporary suffering within a grand eschatological narrative, he provides theological meaning to a demoralized people and fortifies them against assimilation, Latin proselytism, and religious indifference.

IV. Relation to the Orthodox Tradition: Continuity and Innovation

Although Gordios rarely names his sources, his dependence on earlier exegetes—particularly Andrew and Arethas of Caesarea—is evident. He draws from Maximos the Peloponnesian regarding the opening of the seals and from Zacharias Gerganos on certain historical and eschatological themes.⁷ At the same time, Gordios departs from all of these figures by constructing a more coherent and sweeping historicist narrative.

His originality lies not in doctrinal innovation but in recomposition. He reorganizes older material into a structure whose dramatic force, clarity, and pastoral immediacy far surpass earlier efforts. Gordios thus serves as the link between medieval Byzantine eschatology and the modern Orthodox revival of apocalyptic interpretation in the 18th and 19th centuries.

V. Influence and Legacy

The impact of Gordios’s Treatise cannot be measured solely through manuscript transmission but through its influence on later interpreters, including Pantazēs of Larissa, Jean of Myra, Theodoret of Janina, and Kyrillos Lavriotēs⁸ and Apostolos Makrakis. For these authors, Gordios provided the scaffolding on which to build their own historicist readings of Revelation and their understanding of Orthodoxy’s eschatological struggle.

In this sense, Gordios is a foundational architect of the Orthodox historicist tradition:

- He supplies its dual-Antichrist structure.

- He offers a comprehensive historicization of Revelation.

- He interprets political realities through biblical prophecy.

- He establishes Russia as the eschatological protector of Orthodoxy.

- He integrates anti-Islamic and anti-Latin polemics into a unified theological narrative.

Gordios’s Treatise thus stands as one of the most significant and influential eschatological works of the post-Byzantine period, capturing the fears, hopes, and theological imagination of the Greek Orthodox world under Ottoman domination.

Notes

- Christophoros Angelos, Treatise on the Apostasy (c. 1620s).

- Asterios Argyriou, Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse, 305–320.

- Ibid., 337–342.

- Ibid., 342–344.

- Ibid., 330–336.

- Ibid., 326–330.

- Ibid., 348–352.

- Ibid., 353–354.

Chart Summary of Gordios Eschatological System Descrbied in his Treatise

Comparison Chart: Gordios vs. Angelos vs. Makrakis

Three Key Figures in the Eastern Orthodox Historicist Tradition

Bibliography

I. Primary Sources

Greek Patristic and Byzantine Commentaries

Andrew of Caesarea. Commentary on the Apocalypse. In Patrologia Graeca, vol. 106.

Arethas of Caesarea. Scholia on the Apocalypse. In Patrologia Graeca, vol. 106.

Post-Byzantine Commentators

Angelos, Christophoros. Περί Αποστασίας (On the Apostasy). ca. 1620s. Various manuscript traditions.

Gerganos, Zacharias. Ὑπόμνημα εἰς τὴν Ἀποκάλυψιν τοῦ Ἰωάννου. Arta, late 17th century.

Gordios, Anastasios. Περὶ Μαομέθ κατὰ Λατίνων (On Mahomet and Against the Latins). 1717. Extant in several manuscripts. Makrakis, Apostolos. Ἑρμηνεία τῆς Ἀποκαλύψεως (Interpretation of the Apocalypse). Athens, 1873.

Chronographic and Apocryphal Material Cited by Gordios

Malalas, John. Χρονογραφία (Chronicle). In Patrologia Graeca, vol. 97.

Chronicle of Nestor. Paris, Louis. La Chronique dite de Nestor. Paris: 1884.

Methodius of Patara. Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius. Various Greek recensions, 7th–10th c.

Oracles of Leo the Wise (Λόγοι Λέοντος τοῦ Σοφοῦ).

Tarasios of Constantinople. Apocalyptic Homilies.

Anonymous Byzantine Apocalypses (e.g., Pseudo-Daniel, Apocalypse of Andrew the Fool, etc.)

Early Modern Greek Anti-Latin & Anti-Islamic Texts

Karyophylles, Ioannes. Κατὰ τῆς Κατηχήσεως τοῦ Ζαχαρίου Γεργανοῦ (Refutation of the Catechism of Zacharias Gerganos). 17th century.

Terpos, Nektarios. Ὁ σωτηριώδης λόγος (“The Saving Word”). Venice, 1730.

Various anti-Latin treatises circulated anonymously in the 17th–18th centuries.

II. Secondary Sources

Major Scholarly Works

Argyriou, Asterios. Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse à l’époque turque (1453–1821). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1968.

———. “Anastasios Gordios and Islam.” Revue des sciences religieuses 43 (1969): 58–67.

Karayannopoulos, I. Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Apocalyptic Thought. Athens: Academy of Athens, 1995.

Negoită, Octavian-Adrian. Eastern Orthodox Historicism and the Apocalypse: A Study of the Greek Tradition. Bucharest: 2018.

Pissis, Nikolas. The Greek Orthodox Prophetic Tradition in the Early Modern Period. PhD diss., Paris, 2014.

Vasilikou, Artemis. “Eschatology and Identity in Ottoman Greece.” Journal of Early Modern Hellenism 12 (2019): 93–118.

Studies on Angelos, Gordios, and Related Exegetes

Andric, Stanko. “Orthodox Apocalypticism in the Ottoman Balkans.” Byzantinoslavica 67 (2009): 123–145.

Browning, R. “Apostasy and Prophecy in Post-Byzantine Greece.” Balkan Studies 17 (1976): 201–216.

Constantelos, Demetrios. Understanding the Greek Mind: The Orthodox Tradition in Modern Greece. New Rochelle: Caratzas, 1975.

Dragas, George. “The Reception of Andrew and Arethas’ Apocalypse Commentaries in Modern Greek Theology.” The Greek Orthodox Theological Review 45 (2000): 311–340.

Apocalyptic & Historicist Thought in Eastern Orthodoxy

Alexiou, Margaret. “The Apocalyptic Imagination in Post-Byzantine Greece.” In Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 8 (1984): 99–132.

Macrides, Ruth. History and Prophecy in Byzantium. London: Routledge, 2017.

Mango, Cyril. “Byzantine Apocalyptic Literature.” In Oxford Handbook of Apocalyptic Literature, 2016.

On Anti-Latin and Anti-Islamic Polemics

Papadakis, Aristeides. The Christian East and the Rise of the Papacy. Crestwood: SVS Press, 1994.

Khayyat, Mariam. “Greek Christian Polemical Responses to Islam in the Ottoman Period.” Journal of Eastern Christian Studies 62 (2010): 145–170.

Runciman, Steven. The Great Church in Captivity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968.

© 2025, Jonathan Photius