By Jonathan Photius – The NEO-Historicism Research Project

Introduction

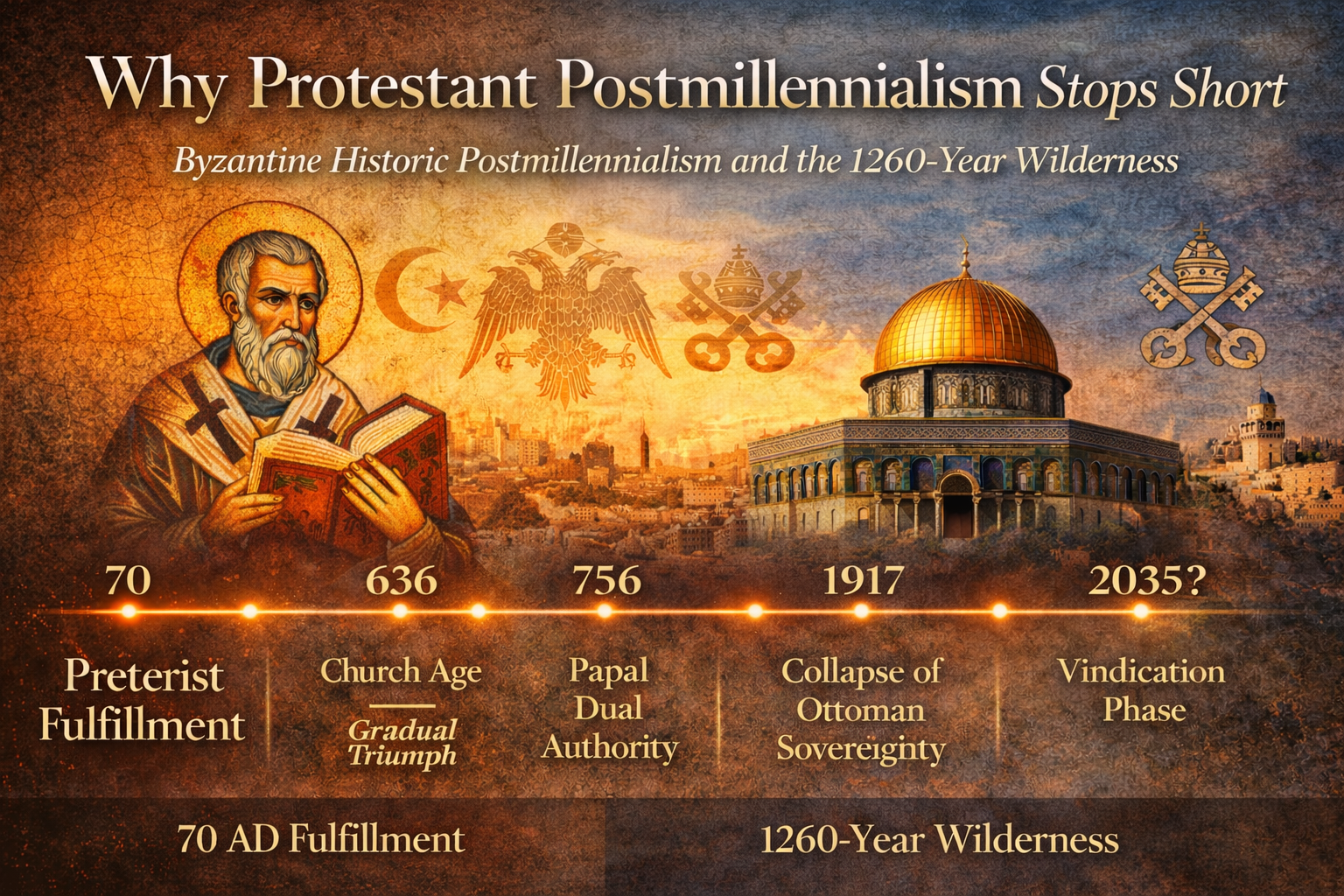

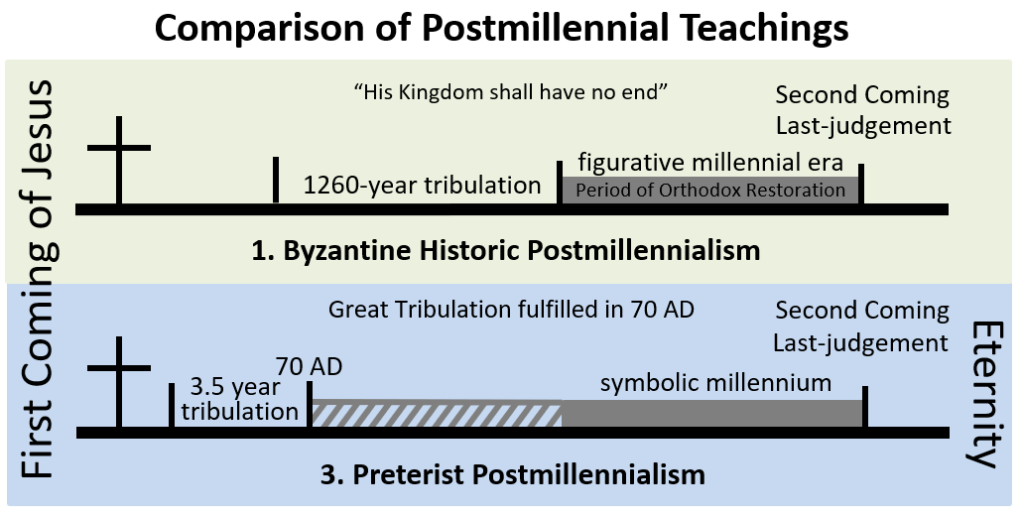

Modern Protestant postmillennialism presents itself as a historically conscious alternative to both dispensational futurism and strict Augustinian amillennialism. It affirms Christ’s present reign, the progressive triumph of the Gospel, and the meaningful transformation of history under divine providence. In its most influential contemporary expression—Preterist Postmillennialism—it interprets much of the Apocalypse as fulfilled in the events surrounding A.D. 70, while maintaining an optimistic expectation of continued cultural and missionary expansion.

In this respect, it shares certain structural affinities with what may be termed Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism: both reject literalistic futurism, both affirm Christ’s present reign, and both anticipate the historical manifestation of His Kingdom prior to the final consummation.

Yet despite this shared optimism, the two traditions diverge at a decisive interpretive threshold. Preterist Postmillennialism resolves the apocalyptic crisis primarily in the first century and proceeds thereafter through a paradigm of progressive expansion. Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism, by contrast, preserves a post-tribulational structure in which the Church undergoes an extended wilderness period—symbolized by the 1260 days of Revelation—before entering a historical phase of vindication.

This essay argues that the divergence is not accidental but theological and ecclesiological. Protestant postmillennialism remains constrained by its Augustinian inheritance and its suspicion of extended chronological mapping, whereas Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism preserves an ecclesial-historicist reading of Revelation structured around symbolic yet chronologically meaningful durations—most notably the 1260-year tribulational period of the woman/church against an unbounded Satan interpreted through the day-year principle.

I. Protestant Postmillennialism: Historical Optimism without Prophetic Chronology

Classical Protestant postmillennialism, as articulated by Loraine Boettner and developed within the broader Princeton tradition (e.g., B. B. Warfield), interprets the “millennium” of Book of Revelation 20 as the present reign of Christ manifested through the Church.¹

Boettner explicitly rejects premillennial literalism and affirms that the thousand years represent a prolonged Gospel era characterized by the gradual Christianization of society.² This reading is structurally optimistic and historically oriented.

However, Protestant (preterist) postmillennialism generally resists sustained chronological mapping of apocalyptic symbols. Durational numbers such as 1260 days, 42 months, or “time, times, and half a time” are rarely interpreted through a consistent day-year hermeneutic. Nor are successive seals, trumpets, and bowls typically aligned with conciliar history, doctrinal crises, or ecclesial epochs in a systematic manner.

History illustrates the Kingdom’s growth; it does not constitute the sequential fulfillment of prophetic time.

This methodological restraint is deliberate.

II. The Augustinian Settlement and Western Eschatological Caution

The decisive Western turning point remains Augustine of Hippo.

In The City of God, Augustine rejected literal chiliasm and identified the millennium with the present reign of Christ through the Church.³ This interpretation spiritualized the thousand years and detached Revelation 20 from concrete chronological sequencing.

Augustine’s concern was pastoral and anti-sectarian. Earlier chiliastic expectations—especially when tied to political upheaval—risked destabilizing ecclesial order.⁴ His solution preserved orthodoxy by minimizing apocalyptic chronology.

Western theology inherited not only Augustine’s conclusions but his caution: prophecy must not be mapped too precisely onto unfolding history.

This suspicion is codified in modern Reformed treatments such as D. H. Kromminga’s The Millennium in the Church, which rejects both dispensational literalism and speculative historicist mapping.⁵ Revelation may symbolize spiritual conflict, but it must not function as a detailed chronological chart.

Thus Protestant postmillennialism is permitted—so long as it remains non-historicist.

III. Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism and the 1260-Year Tribulation

By contrast, the Byzantine exegetical tradition preserved a distinct ecclesial historicism.

From Andrew of Caesarea onward, the Apocalypse was read as a symbolic but continuous narrative of Church history.⁶ While Andrew avoided reckless speculation, he treated apocalyptic sequences as historically unfolding realities within the life of the Church.

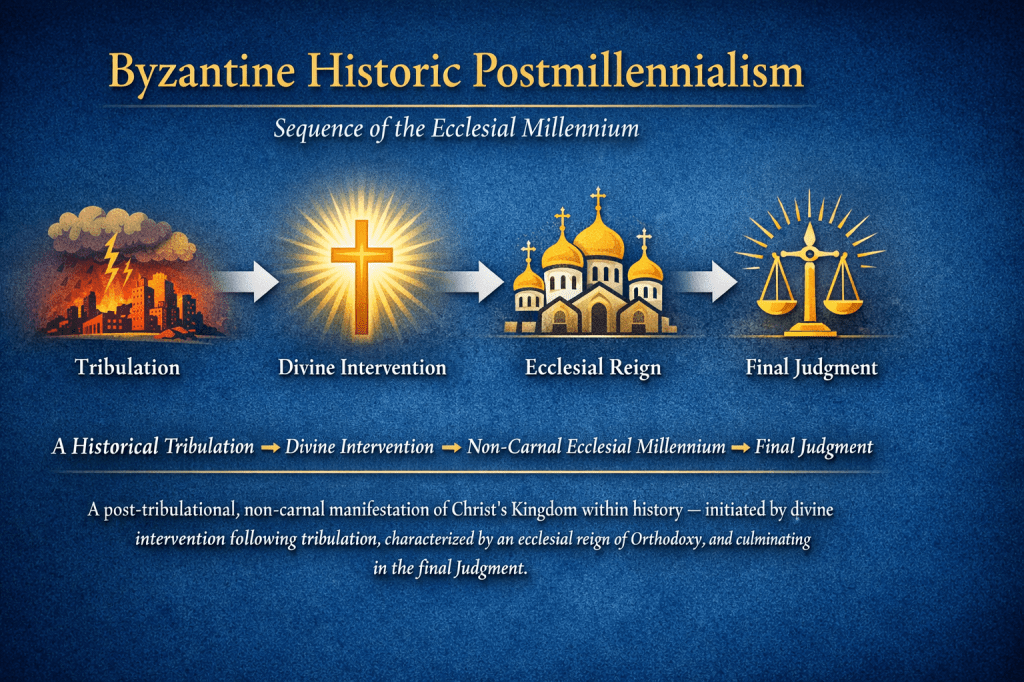

In its mature post-Byzantine development, this tradition came to interpret the 1260 days (Rev 11–13) according to the day-year principle, yielding a prolonged tribulational era. Within Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism, the 1260-year period represents an extended condition of ecclesial oppression, doctrinal conflict, and imperial-religious distortion. The “Beast” is interpreted corporately and historically rather than futuristically or exclusively individually.

The millennium that follows is not a literal first-resurrection kingdom but the historical vindication and flourishing of Orthodoxy after the tribulational age. The thousand years remain symbolic of fullness and covenantal completeness, yet historically embodied.

Chronology is therefore symbolic yet concrete—measured not in speculative futurism, but in retrospective ecclesial discernment.

IV. Patristic Chiliasm Reconsidered: Literalism or Symbolic Expectation?

The Western narrative often portrays early chiliasm as uniformly literal and politically combustible. However, closer examination suggests greater nuance.

Justin Martyr affirms a thousand-year reign in Dialogue with Trypho, yet situates it within prophetic symbolism and eschatological mystery.⁷

Irenaeus of Lyons, in Against Heresies, describes a millennial reign but embeds it within typological recapitulation theology.⁸ His concern is anti-Gnostic realism, not speculative chronology.

Even where literal language appears, the thousand years function covenantally—signifying divine completeness rather than actuarial precision.

Later Fathers such as Origen of Alexandria explicitly spiritualized apocalyptic imagery, while Eusebius of Caesarea criticized crude literalism associated with Papias.⁹

The patristic record therefore reveals diversity rather than uniform literalism. Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism may be understood as synthesizing this diversity:

- Retaining historical expectation

- Rejecting literal first-resurrection materialism

- Preserving symbolic duration

- Integrating fulfillment into conciliar Church history

V. Two Ecclesiologies, Two Epistemologies

The divergence ultimately concerns ecclesiology.

Protestant Preterist Postmillennialism

- History confirms theology

- Revelation symbolizes spiritual realities

- Chronology is minimized

- Stability is preserved through interpretive restraint

Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism

- History is the medium of prophecy

- Revelation narrates ecclesial development

- Chronology functions symbolically yet historically

- Stability is preserved through conciliar authority

Western theology fears that structured historicism leads to sectarianism. The Byzantine tradition demonstrates that historicism, when embedded within sacramental and conciliar continuity, need not generate rupture.

VI. The 1260-Year Tribulation: Chronological Structure within Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism

A defining feature of Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism is the interpretation of the 1260 days (Rev 11:3; 12:6; 13:5) according to the prophetic day-year principle, whereby one symbolic “day” corresponds to one historical year.¹⁰ Rooted in biblical precedents (Ezek 4:6; Num 14:34), this hermeneutic permits apocalyptic durations to function as extended historical epochs rather than brief literal intervals.

Unlike Protestant postmillennialism, which typically leaves these numbers either symbolically generalized or confined to first-century fulfillment, Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism treats the 1260 years as a prolonged ecclesial wilderness phase (Rev 12), characterized by sustained yet divinely preserved tribulation.

The “Beast” in this framework is neither exhausted in Nero nor confined to a single future individual. It represents a corporate historical system—religio-political authority manifesting across centuries in varying institutional forms.

The millennium that follows is not a literal biological resurrection preceding the Parousia. It is the historical vindication and flourishing of Orthodoxy—the “millennial phase” of the Kingdom within history—prior to final consummation.

A. Major Starting-Point Models within the 1260-Year Framework

Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism allows multiple historically defensible starting points. These are interpreted retrospectively rather than predictively and function as theological readings of history rather than speculative forecasts.

Model 1: The Islamic Ascendancy Model (c. 636–638 AD)

Primary Starting Point: Fall of Jerusalem under Islamic conquest (636–638 AD).

Under a geometric (prophetic 360-day year) reckoning:

636–638 + 1260 years ≈ 1896–1898 AD.

This terminus falls within the late Ottoman era, immediately preceding the collapse of uninterrupted Islamic imperial control over Jerusalem.

If, however, one converts prophetic years (360-day basis) into solar equivalence (365.25-day year), the duration expands proportionally:

1260 × (365.25 ÷ 360) ≈ 1278–1279 solar years.

Applied to 636–638:

636–638 + ~1278 ≈ 1916–1918 AD.

This corresponds with:

• The British capture of Jerusalem (1917)

• The dissolution of Ottoman sovereignty

• The Balfour Declaration (1917)

Within Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism, such convergence is interpreted structurally rather than predictively. The early twentieth century marked the exhaustion of continuous Islamic imperial governance over Jerusalem and the broader Levant.

Secondary Anchor: The Dome of the Rock (688 AD)

A second anchor within this model is the construction of the Dome of the Rock (688 AD), which represented not merely political control but explicit religious assertion over the Temple Mount.

From this symbolic architectural marker:

688 + 1260 geometric years = 1948

688 + ~1278 solar-adjusted years = 1966–1967

These dates coincide with:

• 1948 – Establishment of the modern State of Israel

• 1967 – Israeli control of East Jerusalem following the Six-Day War

Again, within this framework these convergences are not treated as dispensational fulfillments but as structural ruptures in uninterrupted Islamic sovereignty over Jerusalem.

The emphasis remains ecclesial and civilizational rather than nationalist or geopolitical.

The Crusader Interruption (1099–1187)

Between 1099 and 1187, Jerusalem was under Crusader control for approximately 87–88 years. One might therefore ask whether the 1260-year span requires chronological extension to preserve a full Islamic occupation period.

However, Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism does not treat the 1260 as a municipal stopwatch but as a civilizational condition. Islamic dominance over Eastern Christianity persisted broadly across the Near East despite the temporary Latin occupation of Jerusalem.

Thus, the 1260-year period is best understood as describing sustained ecclesial marginalization rather than uninterrupted territorial possession of the Holy City.

The question of an additional 88 years extension to fully complete a 1260-year domination of Jerusalem by Islam remains to be seen.

Theological Framing of the Islamic Model

Within the Revelation 12 paradigm:

The woman (the Church) is nourished in the wilderness for 1260 days.

The Islamic ascendancy model describes:

• Loss of ancient patriarchal sees

• Demographic contraction

• Political subordination

• Yet ecclesial preservation

The early twentieth-century rupture in Islamic imperial continuity marks not the Parousia but a transition from uninterrupted wilderness conditions to a new historical phase.

Model 2: The Iconoclastic-Imperial Crisis Model (c. 726–730 AD)

Starting Point: Outbreak of Iconoclasm under Leo III.

1260-Year Terminus: c. 1986–1990 AD.

Here the tribulation is doctrinal and imperial, encompassing:

• Iconoclasm

• Papal-imperial rupture

• Crusader occupation (1204)

• Ottoman domination

• Modern secularization

The collapse of Soviet atheism (1989–1991) becomes symbolically significant within this pattern.

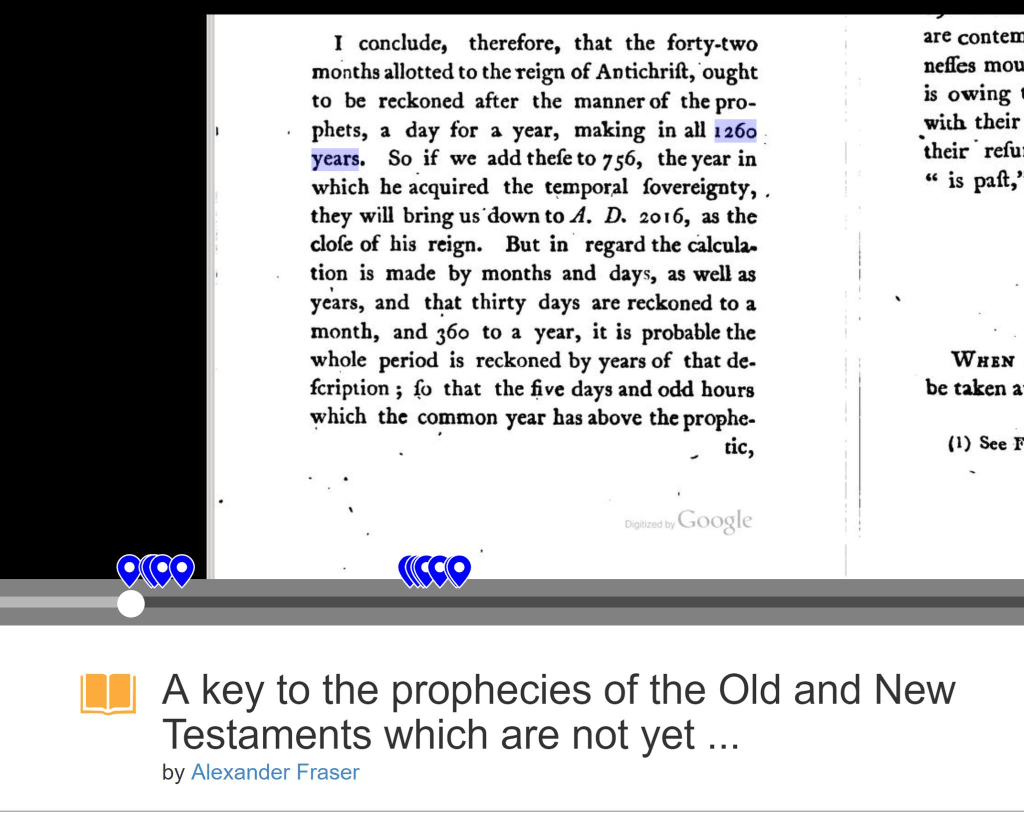

Model 3: The Papal Dual-Authority Model (756 AD)

Starting Point: Donation of Pepin (756 AD), establishing Papal temporal sovereignty.

Unlike the 538 AD Justinian model frequently used in Protestant polemics, 756 represents the first sustained fusion of:

• Spiritual authority

• Territorial political sovereignty

The “two horns” imagery (Rev 13:11) coheres structurally with dual authority.

This starting point also was recognized by Western Protestant historicists such as:

- Adam Clarke

- Alexander Fraser

Fraser, in A Key to the Prophecies of the Old and New Testaments (1806) applies the day-year principle to the 42 months and identifies 756 as the year Papal temporal sovereignty began, yielding a prophetic terminus around A.D. 2016 when reckoned in 360-day prophetic years.¹¹ He writes:

“I conclude… that the forty-two months allotted to the reign of Antichrist ought to be reckoned after the manner of the prophets, a day for a year, making in all 1260 years. So if we add these to 756, the year in which he acquired the temporal sovereignty, they will bring us down to A.D. 2016, as the close of his reign…”

If we use a solar-adjusted calculation instead using 365.25 days/year we get:

756 + ~1278 ≈ 2034–2035 AD.

Regardleass, within Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism, such calculations illustrate the structural exhaustion of a religio-political configuration rather than a predictive eschatological event.

Model 4: The Constantinopolitan Schism Model (1054 AD)

Starting Point: The Great Schism.

1260-Year Terminus: c. 2314 AD (future-oriented).

This model interprets the tribulation as ecclesial fragmentation within Christendom and remains open-ended. Note however that the “two horns” of the “apparent Lamb” or Vicar of Christ began around the time of the Donation of Constantine, so a 1260-year calculation from the Great Schism is unlikely

Conclusion

Where Western Preterist Postmillennialism compresses the apocalyptic drama largely into the first century—identifying the Beast with Nero and the tribulation with the events surrounding A.D. 70—Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism preserves an extended ecclesial horizon. The former resolves the prophetic crisis early and thereafter proceeds primarily by theological optimism; the latter retains apocalyptic structure across centuries of imperial conflict, doctrinal struggle, and ecclesial preservation.

This chronological compression in Preterist Postmillennialism yields both strength and limitation. Its strength lies in safeguarding the finality of Christ’s victory in the apostolic era. Its limitation lies in the relative underdevelopment of subsequent ecclesial history as prophetic narrative. Revelation becomes largely fulfilled background rather than continuing ecclesial self-interpretation.

Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism, by contrast, allows Revelation 12–13 to unfold across extended historical epochs. The 1260 days signify not merely a three-and-a-half-year persecution, but a prolonged wilderness condition in which the Church survives under successive religio-political pressures. Islam, Papal temporal sovereignty, imperial iconoclasm, and modern secularization are not extraneous to the apocalyptic narrative; they are structurally integrated within it.

Revelation 12 in particular depicts the woman nourished in the wilderness while the dragon continues his assault. The adversary is neither absent nor historically inert; he persecutes, deceives, and wars against the saints across the duration of the wilderness period. The Church suffers, yet she is preserved. She is marginalized, yet not extinguished. Such a portrayal sits uneasily with interpretations that confine the dragon’s decisive activity entirely to the first century or that treat his binding as rendering him historically inactive from the Church’s inception. Instead, the Apocalypse narrates a prolonged ecclesial struggle in which the Body of Christ endures assault, overcomes heresy, survives imperial domination, and emerges into vindication through sustained historical fidelity.

The difference, therefore, is not optimism versus pessimism, nor literalism versus symbolism. It is whether the Apocalypse remains primarily a first-century resolution or becomes an enduring ecclesial chronicle.

At its deepest level, the divergence concerns not only chronology but Christology. Preterist Postmillennialism tends to frame Revelation as the vindication of Christ in the first century followed by the gradual expansion of His Kingdom. Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism, by contrast, reads the Apocalypse as the Paschal pattern of Christ recapitulated in His Body. The Church enters wilderness, suffers marginalization, undergoes historical “death” under prolonged religio-political pressures, and emerges into vindication before the final consummation. The millennium is thus not merely the quantitative increase of Gospel influence, but the resurrectional flourishing of the Body of Christ after extended tribulation.

In this sense, Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism does not merely extend Protestant optimism; it reframes the Apocalypse as the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of the Church herself, lived across centuries before the final appearing of her Lord. The Apocalypse is not simply the story of an early victory followed by steady advance. It is the drama of Christ’s life recapitulated in His Body until history itself reaches its consummation.

Notes

- Loraine Boettner, The Millennium (Philadelphia: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1957), 14–32.

- Ibid., 3–10.

- Augustine, The City of God, trans. Henry Bettenson (London: Penguin, 2003), 20.7–9.

- Ibid., 20.17.

- D. H. Kromminga, The Millennium in the Church (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1945), 210–230.

- Andrew of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse, PG 106.

- Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, 80–81.

- Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 5.32–36.

- Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 3.39.

Appendix A

PRETERIST Chronological Compression vs. Structured Chronological Extension: A Comparative Framework

| Category | Preterist Postmillennialism | Byzantine Historic Postmillennialism |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Fulfillment Anchor | 70 AD (Destruction of Jerusalem) | Multi-century ecclesial unfolding |

| Beast (Rev 13) | Nero / First-century Rome | Corporate religio-political systems |

| 42 Months / 1260 Days | Jewish War (66–70 AD) | 1260-year ecclesial wilderness |

| Revelation 12 | Early persecution of the Church | Extended wilderness condition of the Church |

| Chronological Scope | Compressed into first century | Structured across centuries |

| Millennium (Rev 20) | Present Church age beginning after 70 AD | Vindication phase following tribulation |

| View of Church History | Gospel expansion after resolved crisis | Paschal recapitulation across epochs |

| Islam | Not structurally integrated | Integrated within wilderness phase |

| Papal Temporal Authority | Often secondary or post-apocalyptic | Integrated within 1260-year structure |

| Chronological Method | Literal first-century limitation | Day-year principle (prophetic duration) |

| Eschatological Risk | Avoids extended speculation | Retains structure within ecclesial safeguards |

| Narrative Shape | Early climax → gradual expansion | Tribulation → exhaustion → vindication |