By: Jonathan Photius, The NEO-Historicism Research Project

I. Introduction: Why “Babylon” Cannot Be Reduced to Rome Alone

Within Christian interpretation of Revelation, “Babylon” has often been reduced to a single historical referent, most commonly identified with pagan or papal Rome (or Jerusalem). While such identifications have a long pedigree, they also risk flattening the rich biblical and patristic usage of Babylon as a symbol that transcends one city or era. In the prophetic scriptures, Babylon functions not merely as a geographical location but as a system of domination, impiety, and captivity that may reappear in different historical forms.¹

The post-Byzantine Orthodox commentator Theodoret of Ioannina offers a strikingly different and largely forgotten perspective. Writing after the fall of Constantinople, Theodoret interprets Babylon through a historicist lens shaped by Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, and Revelation. In his framework, Babylon is not fixed to Rome alone, nor is it confined to antiquity. Instead, it names a recurring historical reality in which sacred centers of the Church fall under impious rule.²

This approach leads Theodoret to a provocative conclusion: Constantinople itself may become “Babylon” under certain historical conditions, without losing its deeper vocation as the New Jerusalem. This article examines that claim by summarizing Theodoret’s interpretive system as presented in Les Exégèses, focusing on his use of the Old Testament prophets and his reading of Revelation 17–18. A fuller engagement with his Greek manuscripts will follow in later work.

II. Theodoret’s Historicist Framework: Two Systems in History

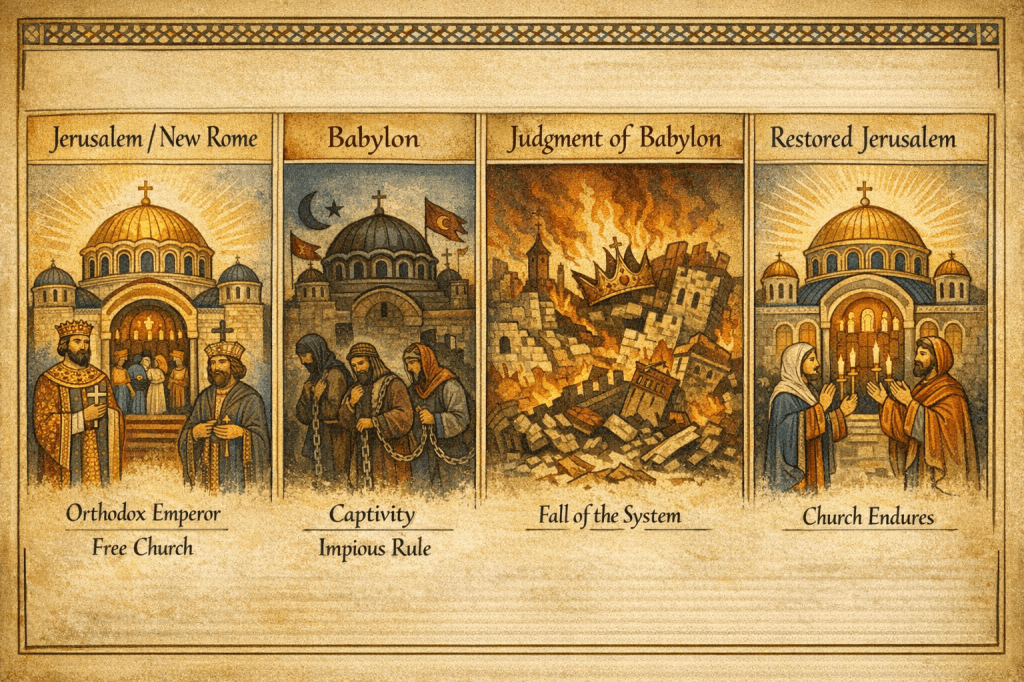

At the foundation of Theodoret’s exegesis lies a simple but far-reaching principle: history unfolds as a struggle between two systems, the system of God and the system of evil. These systems are not abstractions; they are embodied in concrete political, religious, and ecclesial realities across time.³

Cities and empires are therefore not permanently sanctified or permanently condemned. Their prophetic identity depends on who reigns and what faith is confessed. A city may function as Jerusalem at one moment and as Babylon at another, depending on whether it serves as a seat of Orthodox worship or as a throne of impious domination.

Table 1. Jerusalem vs. Babylon in Theodoret’s System

| Historical Condition | Prophetic Identity |

|---|---|

| Orthodox emperor and free Church | Jerusalem / New Rome |

| Infidel or heretical rule | Babylon |

| Captivity and persecution | Babylonian servitude |

| Liberation and restoration | Return to Jerusalem |

Babylon, in this framework, is not a rival church but a condition of captivity.

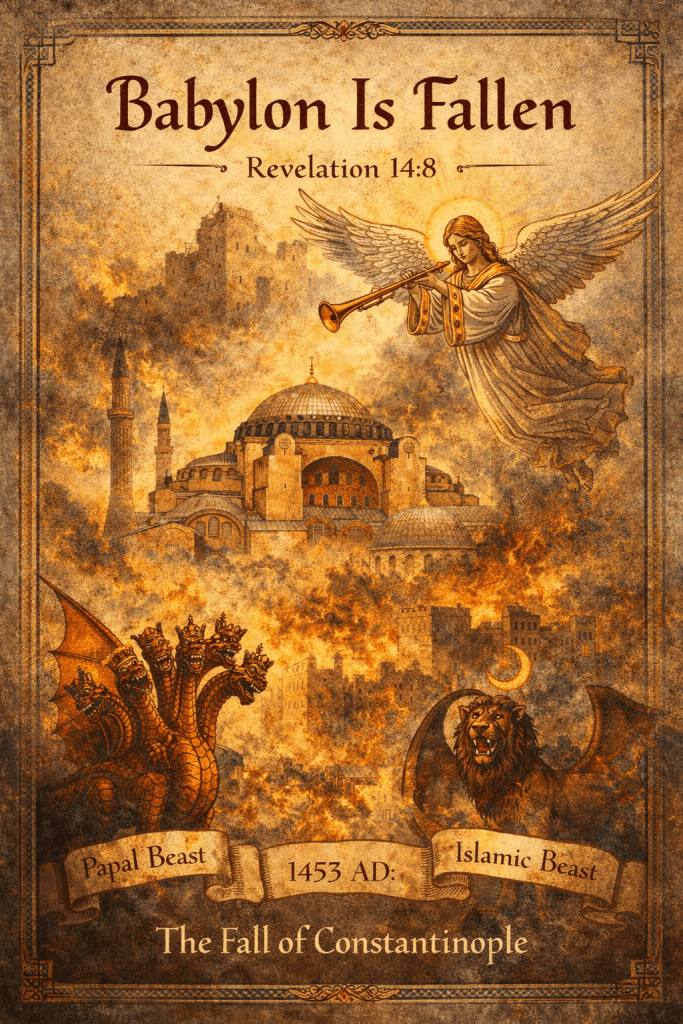

III. Constantinople as Babylon: A Conditional and Historical Identity

Within this framework, Theodoret’s treatment of Constantinople becomes intelligible. Constantinople is not Babylon by nature, nor does it lose its sacred character permanently. Rather, it becomes Babylon insofar as it becomes the seat of impious rule, specifically under Ottoman domination.⁴

As the capital of Orthodoxy, Constantinople had long been regarded as the New Rome and, in a theological sense, the New Jerusalem. When that same city fell under Islamic rule, Theodoret interprets the event not simply as a political catastrophe but as a Babylonian captivity of the Church.

Table 2. Constantinople Across Salvation History (Theodoret)

| Historical Phase | Prophetic Identity |

|---|---|

| Byzantine Orthodox capital | Jerusalem / New Rome |

| Ottoman occupation | Babylon |

| Post-Babylon liberation | Restored Jerusalem |

This distinction allows Theodoret to speak of judgment without annihilation and captivity without despair.

IV. Isaiah and the Captive Church

(Isaiah 13–14; 21–22; 47)

Isaiah provides the backbone of Theodoret’s Babylon theology. Rather than restricting Isaiah’s oracles to ancient Mesopotamia, Theodoret reads them as prophetic patterns fulfilled in the history of the Church.⁵

In Isaiah 13–14, Babylon signifies the Church under occupation. Theodoret applies this captivity in a dual manner: in the East, the Church is occupied by infidels; in the West, it is corrupted by heresy. Isaiah 21–22 intensifies this reading by lamenting the servitude of the Church in both Rome and Constantinople, while Isaiah 47 announces the humiliation and fall of the Babylonian system.

Table 3. Isaiah’s Babylon Applied by Theodoret

| Passage | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Isaiah 13–14 | Church occupied by infidels (Constantinople) and heretics (Rome) |

| Isaiah 21–22 | Lament over the servitude of the Church |

| Isaiah 47 | Judgment of Babylon and liberation |

V. Jeremiah and the Judgment of Ottoman Babylon

(Jeremiah 51–52)

Jeremiah’s oracles against Babylon play a decisive role in Theodoret’s thought. Chapters 51–52 are interpreted as announcing the historical destruction of the Babylonian system, not merely its moral exposure. Theodoret explicitly applies these chapters to Constantinople under Ottoman rule.⁶

Table 4. Jeremiah 51–52: From Ancient Babylon to Constantinople

| Element | Application |

|---|---|

| Babylon’s pride | Imperial impiety |

| Divine judgment | Collapse of the ruling system |

| Fall of Babylon | End of Ottoman domination |

| Aftermath | Possibility of restoration |

VI. Ezekiel: Apostasy, Resurrection, and Restoration

(Ezekiel 16; 37–39)

Ezekiel introduces a theology of restoration essential to Theodoret’s system. In Ezekiel 16, Babylon signifies apostasy: Eastern Christians subjected to Islam and Western Christians adhering to Latin heresy.⁷

Ezekiel 37, however, announces resurrection—the revival of the Church and its historical witness. Ezekiel 38–39 completes the arc with the defeat of the final enemies of God’s people.

Table 5. Ezekiel’s Movement in Theodoret’s Historicism

| Passage | Theme | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ezekiel 16 | Apostasy | East and West |

| Ezekiel 37 | Resurrection | Restoration of Church |

| Ezekiel 38–39 | Final defeat | End of Babylonian powers |

VII. Daniel 11:45 and the Geography of Babylon

Daniel 11:45 provides geographic specificity to Theodoret’s reading. The verse describes an impious power establishing itself “between the seas” upon a “glorious holy mountain” before its downfall. Theodoret applies this directly to Ottoman Constantinople.⁸

Table 6. Daniel 11:45 in Theodoret’s Reading

| Phrase | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| “Plant the tents of his palace” | Ottoman imperial establishment |

| “Between the seas” | Constantinople |

| “Holy mountain” | Orthodox sacred center |

| “He shall come to his end” | Collapse of Babylonian rule |

VIII. Revelation 17–18: Babylon Judged, the City Liberated

Revelation 17–18 gathers the prophetic strands traced by the Old Testament. Babylon in Revelation is the culmination of the same system denounced by Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel.⁹

For Theodoret, Babylon’s fall does not mean the destruction of Constantinople. Rather, Babylon is destroyed in the city, not as the city. The ruling system is judged; the Church endures.

Babylon, Constantinople, and the Prophets

A Prophet-by-Prophet Chart: Isaiah / Jeremiah / Ezekiel → Constantinople

| Prophet | Key Passages | Babylon Meaning in Theodoret | Constantinople Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jeremiah | Jer 51–52 | Babylon = seat of impious dominion to be judged and destroyed | Constantinople as Babylon when ruled by the Turkish sultanate; liberation follows judgment |

| Isaiah | Isa 13–14 | Babylon = Church in captivity | Dual captivity: Constantinople (Islam) + Rome (Latin heresy) |

| Isaiah | Isa 21–22 | Lament over servitude of the Church | Explicitly names Rome and Constantinople as enslaved ecclesial centers |

| Isaiah | Isa 47 | Fall and humiliation of Babylon | Applied to the downfall of the Ottoman Babylon, coordinated with Rev 17 |

| Ezekiel | Ezek 16 | Apostate “systems” abandoning Orthodoxy | East → conversion to Islam (Constantinople); West → Latin impiety |

| Ezekiel | Ezek 37–39 | Resurrection after judgment; defeat of enemies | Restoration of Church and empire after Babylon’s fall |

| Daniel | Dan 11:45 | Final encampment before destruction | Ottoman Constantinople (“holy mountain… between the seas”) |

IX. Conclusion: Babylon Judged, the Church Endures

Theodoret of Ioannina presents a coherent Orthodox historicist interpretation of Babylon that resists reductionism and speculation. Babylon is a system that rises and falls within history; the Church, though captive for a time, remains.

Constantinople’s Babylonian phase is conditional and temporary. Isaiah laments captivity, Jeremiah announces judgment, Ezekiel promises resurrection, Daniel situates Babylon geographically, and Revelation discloses its final fall. Through all of this, the Church endures, awaiting restoration.

This study has intentionally limited itself to the contours of Theodoret’s system as preserved in Les Exégèses. A deeper engagement with his Greek commentary on Revelation will follow as we translate the original Greek text. Even so, his voice already emerges as a powerful witness to an Orthodox eschatology that is ecclesial, historical, and sober.

Footnotes (Chicago Style)

- Rev 17–18; cf. Isa 13–14.

- Asterios Argyriou, Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse à l’époque turque (Geneva: Droz, 1982), chap. 8.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., chap. 8.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., chap. 9.

- Rev 17–18; Argyriou, Les Exégèses, chap. 8.

Appendix A: Direct comparison: Theodoret’s Babylon schema vs. Makrakis (Rev 17–18)

Theodoret (via Les Exégèses ch. 8)

Babylon is a “system of Evil” that can be embodied by multiple empires and cities; Constantinople itself can toggle between Jerusalem (Orthodox imperial seat) and Babylon (Ottoman seat).Theodoret of Ioannina Les Exege…

Makrakis (Rev 17–18 emphasis, Concord Square material)

Makrakis is far more singular in Rev 17’s referent: he explicitly identifies the Great Harlot / Mystery Babylon with Papal Rome / the Roman Church, and he grounds “Babylon” in Rome’s doctrinal deception and the “wine of fornication” as false teaching.

Comparison grid: Theodoret vs. Makrakis

| Category | Theodoret | Makrakis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary referent of “Babylon” in Rev 17–18 | Multi-embodiment “system”: includes Constantinople under Turks, and also frames Rome under Latin heresy as a Babylon-captivity axis. Theodoret of Ioannina Les Exege… | Papal Rome / Roman Church as the Great Harlot; “Babylon” = Rome’s doctrinal “confusion,” “wine of fornication” = false teaching. |

| Mechanism | Occupation + captivity (Islam) and heresy + corruption (Latinism) both count as Babylonizing forces. Theodoret of Ioannina Les Exege… | Doctrinal intoxication and ecclesio-political domination by Papal claims. |

| Relationship of Constantinople to Babylon | Constantinople can become Babylon when enthroned by the sultan. Theodoret of Ioannina Les Exege… | Constantinople is not the center of Rev 17–18 in the quoted Makrakis material; his focus is Rome-as-harlot. |

Comparison Summary: Theodoret vs. Makrakis on Revelation 17–18

- Scope of “Babylon”

- Theodoret: A transhistorical system of evil embodied in different centers at different times.

- Makrakis: Primarily Papal Rome as Mystery Babylon.

- Constantinople’s Status

- Theodoret: Can become Babylon when ruled by infidels, yet remain destined for restoration.

- Makrakis: Constantinople is not the primary referent of Rev 17–18.

- Mechanism of Babylonization

- Theodoret: Occupation (Islam) and heresy (Latinism) both qualify as Babylonian captivity.

- Makrakis: Doctrinal intoxication (“wine of fornication”) and ecclesial corruption.

- OT–Revelation Integration

- Theodoret: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel are directly mapped onto Revelation’s Babylon.

- Makrakis: Revelation dominates; OT is supporting rather than determinative.

- Eschatological Outcome

- Theodoret: Babylon is destroyed; Constantinople is liberated and restored.

- Makrakis: Focus on judgment of Papal Rome and vindication of Orthodoxy.

- Ecclesial Emphasis

- Theodoret: Babylon is measured by its relation to Orthodoxy’s center.

- Makrakis: Babylon is measured by false teaching and ecclesial tyranny.

- Political vs. Ecclesial Weight

- Theodoret: Allows strong historical-political embodiment.

- Makrakis: Keeps Babylon largely ecclesio-doctrinal.

© 2026 by Jonathan Photius