By: Jonathan Photius – NEO-Historicist Research Project

Abstract

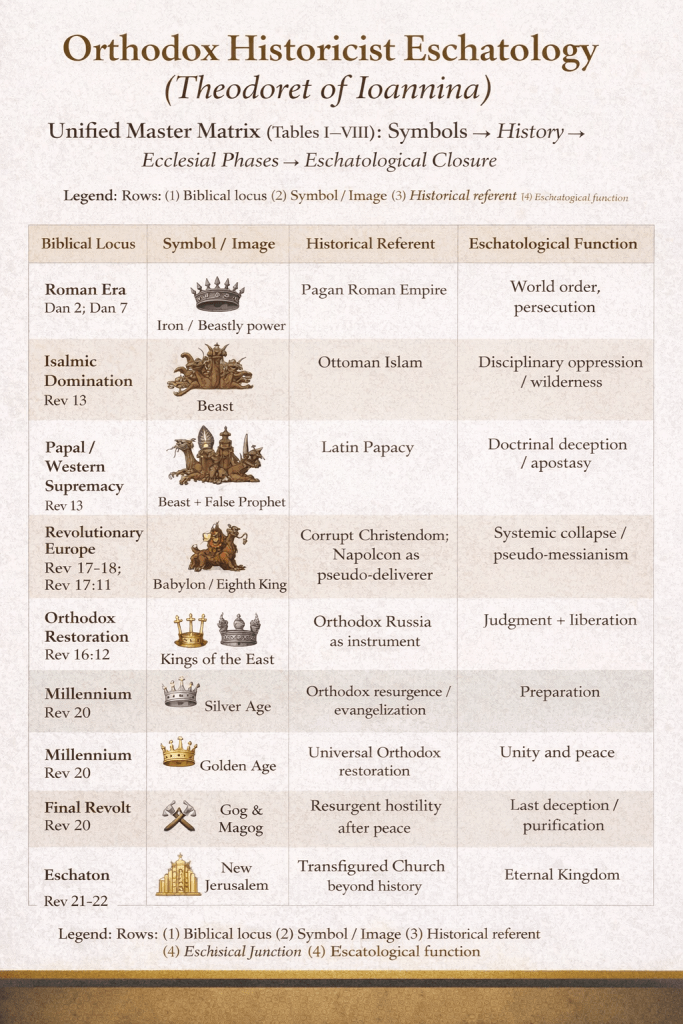

This article presents the first full reconstruction of the eschatological system articulated in Theodoret of Ioannina’s Exegesis of the Old and New Testament, read in conjunction with his earlier Exegesis of the Apocalypse. Far from representing a peripheral or idiosyncratic phenomenon, Theodoret’s work constitutes a coherent Orthodox historicist theology of history, grounded in a conjoined interpretation of Old Testament prophecy, the Johannine Apocalypse, and post-Byzantine ecclesial experience. By integrating biblical symbolism, imperial succession, ecclesiology, and measured historical duration, Theodoret articulates a non-Augustinian eschatology that resists both Western amillennial abstraction and modern futurist speculation. History itself functions as the arena of divine judgment and restoration, culminating not in political utopia but in a preparatory millennium preceding the Parousia.¹

I. Introduction: The Recovery of a Suppressed Orthodox Eschatology

Modern eschatological discourse has been overwhelmingly shaped by Western paradigms. Augustinian amillennialism, Protestant preterism, dispensational futurism, and postmillennial optimism dominate both academic theology and popular interpretation. Within this landscape, Orthodox historicist traditions—especially those formed under Ottoman domination—have been marginalized, caricatured, or dismissed as politically motivated prophecy. The work of Theodoret of Ioannina has suffered precisely this fate.²

Yet the Exegesis of the Old and New Testament does not represent an isolated outburst of apocalyptic enthusiasm. When read in continuity with the Exegesis of the Apocalypse and analyzed through the concordance tables preserved in Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse à l’époque turque (1453–1821), it becomes clear that Theodoret developed a systematic and internally disciplined eschatological framework.³ His interpretations are not episodic; they are rule-governed. Symbols retain stable meanings, historical referents shift according to providence, and ecclesial continuity governs interpretation.

According to Asterios A. Agyriou, Theodoret of Ioannina’s Conjoined Exegesis of the Old and the New Testament represents the final stage of his literary production and was written around 1817, within the immediate post-Napoleonic context and during the reign of Alexander I of Russia.¹

This article argues that Theodoret’s eschatology belongs to a continuous Orthodox historicist trajectory extending from Byzantine exegetes through post-Byzantine interpreters and into the nineteenth century. It further argues that this tradition cannot be assimilated to Augustinian amillennialism without doing violence to its structure, chronology, and theology of history.

II. Methodological Foundations: Conjoined Interpretation and Symbolic Stability

The defining feature of Theodoret’s method is what modern scholarship has termed exégèse conjuguée—a conjoined interpretation of Old Testament prophecy, New Testament teaching, and the Apocalypse of John.⁴ Scripture is not divided into sealed dispensations; nor is prophecy exhausted by a single historical moment. Rather, prophetic symbols function typologically across time.

1. Unity of Testaments

For Theodoret, Daniel, Ezekiel, the Psalms, the Gospels, and Revelation form a single prophetic continuum. Daniel’s beasts recur in Revelation’s beasts; Ezekiel’s Gog and Magog reappear in Revelation 20; the Ark of Noah prefigures the Church preserved in tribulation.⁵ This unity is not allegorical in the modern sense. It is historical and ecclesial.

2. Stability of Symbol, Mobility of Referent

A central rule governs Theodoret’s exegesis: symbols remain stable in meaning even as their historical referents change. Thus, the “Beast” always signifies an imperial persecuting power hostile to Orthodoxy, but it does not always signify the same empire. Islam, the Papacy, and revolutionary Western power can each function as beastly manifestations without collapsing the symbol itself.⁶ This principle is demonstrated schematically in Tables I–III of the concordance.⁷

Table I. Core Hermeneutical Principle of Theodoret’s Eschatology

| Element | Principle |

|---|---|

| Scriptural unity | Old Testament, Gospels, and Apocalypse form a single prophetic continuum |

| Symbolic meaning | Stable and non-arbitrary |

| Historical referent | Variable across epochs |

| Interpretive authority | Ecclesial, not private |

| Verification | History confirms interpretation retrospectively |

Table II. Major Apocalyptic Symbols and Their Historicist Meaning

| Biblical Symbol | Meaning | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Ark of Noah | Orthodox Church | Preservation during judgment |

| Woman in the wilderness (Rev 12) | Orthodox Church | Concealment and protection |

| Beast from the Sea | Imperial power hostile to Orthodoxy | Political persecution |

| Beast from the Earth | False ecclesial authority | Doctrinal deception |

| Babylon | Corrupt Christendom / apostate civilization | Moral and spiritual collapse |

| New Jerusalem | Restored Orthodox Church | Pre-eschatological illumination |

Table III. Empire and Sacred History (Daniel–Revelation Continuity)

| Danielic Image | Revelation Parallel | Historical Identification |

|---|---|---|

| Iron Kingdom | Beastly dominion | Ottoman Empire |

| Bronze element | False prophet | Papal / Latin Christendom |

| Ten horns | Fragmented Western powers | Post-medieval Europe |

| Eighth king (Rev 17:11) | False liberator | Napoleon |

| Kings of the East | Agents of judgment | Russia |

3. Ecclesial Hermeneutic

Interpretation belongs to the Church as a historical body. The Woman of Revelation 12 is not an abstract ideal; she is the Orthodox Church, historically driven into the wilderness during the Ottoman period and preserved through monastic life.⁸ History does not replace theology; it becomes its field of manifestation.

III. Theodoret against Western Eschatological Paradigms

A. Against Augustinian Amillennialism

Augustine’s identification of the millennium with the present Church age collapses Revelation’s temporal architecture into a generalized spiritual present.⁹ In doing so, it eliminates the expectation of a distinct historical phase of restoration prior to the Parousia. Theodoret’s system cannot be accommodated within this framework. His concordance tables explicitly distinguish between periods of persecution, concealment, judgment, restoration, and final consummation (Tables IV–V).¹⁰

Table IV. Antichrist as System (Not Individual)

| Component | Manifestation | Role |

|---|---|---|

| Political | Islamic empire | Physical oppression |

| Doctrinal | Papacy | Spiritual deception |

| Civilizational | Revolutionary West | Secular corruption |

| Composite | Antichristic system | Sustained opposition to Orthodoxy |

Table V. Chronological Structure of Sacred History

| Period | Description |

|---|---|

| Apostolic era | Foundation |

| Imperial Christian era | Relative peace |

| Ottoman domination (≈1260 years) | Wilderness period |

| Collapse of beastly powers | Judgment phase |

| Silver Age | Orthodox restoration |

| Golden Age | Evangelical illumination |

| Gog and Magog | Final revolt |

| Parousia | End of history |

B. Against Preterism

Preterist readings restrict Revelation’s fulfillment to the first century, severing the Apocalypse from the lived history of the Church. Theodoret rejects this implicitly and explicitly by applying prophetic symbols to the Ottoman period, the Papacy, and modern European upheavals.¹¹ Revelation interprets history beyond Rome.

C. Against Western Postmillennialism

While Theodoret affirms a future historical peace, his millennium is not the product of Western cultural ascendancy or gradual moral progress. It follows judgment, not reform, and is conditioned by repentance and ecclesial unity rather than political triumph.¹²

IV. Empire as Instrument of Divine Judgment

A defining axis of Theodoret’s eschatology is the theology of empire. Empires are neither neutral nor accidental; they function as providential instruments.

1. The Iron Kingdom: Ottoman Domination

In continuity with Daniel 2 and Daniel 7, Theodoret identifies the Ottoman Empire as the iron kingdom—durable, oppressive, and prolonged.¹³ Its function is disciplinary rather than redemptive, driving the Church into concealment and purification.

2. The Bronze Kingdom: Latin Christendom

Western Christendom, particularly the Papal system, corresponds to the bronze element of Daniel’s schema. Externally Christian yet doctrinally corrupt, it constitutes a second front of oppression—this time through deception rather than force.¹⁴

3. Revolutionary Europe and the Eighth King

Revelation 17:11 introduces the “eighth king,” whom Theodoret identifies with Napoleon.¹⁵ Napoleon is not the final Antichrist but an antichristic embodiment of secularized power and false liberation. This identification marks a significant historical recalibration while preserving symbolic continuity¹⁶

V. Antichrist as System, Not Person

One of the most significant contributions of Theodoret’s eschatology is his rejection of a singular, personalized Antichrist. Antichrist is a system comprising political domination, doctrinal deception, and civilizational corruption.¹⁷

The first Beast manifests as Islamic imperial power; the second Beast manifests as the Papal system; Babylon represents corrupt Christendom and, in its later phase, revolutionary Western ideology.¹⁸ This systemic understanding aligns with Byzantine exegetical precedent and stands in sharp contrast to modern futurist literalism.

VI. The Millennium Recovered: Silver and Golden Ages

Perhaps the most theologically decisive element of Theodoret’s system is his recovery of a real, pre-Parousia millennium.

Table VI. The Millennium in Orthodox Historicism

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Nature | Historical, not eternal |

| Duration | Finite, undefined |

| Character | Peaceful, evangelical |

| Precedes | Final revolt |

| Follows | Collapse of antichristic systems |

| Distinct from | Augustinian amillennialism |

| Distinct from | Western postmillennial optimism |

1. The Silver Age

Following the collapse of oppressive empires, a period of Orthodox peace and evangelization emerges. This “silver age” is marked by restoration rather than perfection.¹⁹

2. The Golden Age

A subsequent “golden age” brings broader unity, conversion of nations, and doctrinal clarity. The Church becomes publicly luminous, preparing humanity for the Parousia.²⁰ The millennium is therefore preparatory, not eternal—a position irreconcilable with Augustinian amillennialism and distinct from Western postmillennial optimism. This structure is synthesized visually in Table VII.²¹

Table VII. Comparison of Eschatological Frameworks

| Feature | Orthodox Historicism (Theodoret) | Augustinian Amillennialism |

|---|---|---|

| Millennium | Future historical phase | Present Church age |

| Role of history | Interpretive arena | Secondary |

| Antichrist | Systemic | Often personal or abstract |

| Church’s future | Restoration before Parousia | No distinct historical phase |

| Revelation | Progressive unveiling | Symbolic recapitulation |

VII. Russia and the Kings of the East

Russia occupies a decisive yet restrained role in Theodoret’s eschatology. Identified with the “kings of the East” (Rev 16:12) and the Church of Philadelphia (Rev 3), Russia functions as an instrument of judgment and liberation, not as the Kingdom of God itself.²²

Crucially, Theodoret explicitly resists theophanic or messianic absolutization of empire. Russia serves the Church; it does not replace her.²³

VIII. Gog and Magog and the Final Revolt

After peace comes deception. Gog and Magog represent the resurgence of hostile forces following the millennium—a final confirmation that history cannot culminate in human perfection.²⁴ Only after this revolt does the Parousia occur.

IX. Conclusion: Toward an Orthodox Reconstruction of Sacred History

Theodoret of Ioannina offers a fully articulated Orthodox historicist eschatology that cannot be reduced to Western categories. His system preserves symbolic realism, historical sequencing, ecclesial centrality, and eschatological restraint. It demonstrates that Orthodox theology possesses its own robust grammar for interpreting history—one neither Augustinian nor futurist.

The recovery of this tradition is not merely antiquarian. In an age of secular empire, ecclesial confusion, and eschatological distortion, Theodoret’s work offers a corrective framework grounded in Scripture, history, and the lived experience of the Church.²⁵

Unified Conjoined Eschatological Matrix (Theodoret of Ioannina)

| Biblical Locus | Symbol / Image | Théodoret’s Interpretation | Historical Referent | Eschatological Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gen 6–9 / Mt 24 | Ark of Noah | Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodoxy | Preservation during tribulation |

| Dan 2 | Iron Kingdom | Empire of iron | Ottoman Empire | Long oppression of the Church |

| Dan 2 | Bronze | Western powers | Papal / Latin West | Heretical domination |

| Dan 7 | Four Beasts | Four imperial systems | Pagan Rome → Papacy → Islam → West | Sequential persecution |

| Dan 7:13–14 | Son of Man | Messianic reign | Christ through history | Authority before Parousia |

| Rev 6 | Seals | Phases of Church suffering | Roman → Islamic → Western | Progressive judgment |

| Rev 8–9 | Trumpets | Warnings & chastisements | Islamic / Western wars | Calls to repentance |

| Rev 11 | Two Witnesses | Orthodox testimony | Clergy & faithful | Perseverance under oppression |

| Rev 11:15 | Kingdom proclaimed | Transfer of dominion | Orthodox resurgence | Beginning of restoration |

| Rev 12 | Woman | Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodoxy | Flight into wilderness |

| Rev 12 | 1260 days | Period of concealment | Ottoman era | Monastic preservation |

| Rev 13 | First Beast | Islam | Ottoman power | Political persecution |

| Rev 13 | Second Beast | Papacy / West | Latin Christianity | Doctrinal deception |

| Rev 17 | Whore of Babylon | Corrupt Christendom | Papacy + West | Spiritual adultery |

| Rev 17:11 | Eighth King | Napoleon | Revolutionary West | Antichristic empire |

| Rev 16:12 | Kings of the East | Orthodox power | Russia | Instrument of judgment |

| Rev 19 | Rider on white horse | Christ in history | Through Orthodox rulers | Victory before millennium |

| Rev 20 | Millennium (1st phase) | Silver age | Orthodox peace | Evangelization |

| Rev 20 | Millennium (2nd phase) | Golden age | Universal Orthodoxy | Preparation for Parousia |

| Rev 20 | Gog & Magog | Final revolt | Western / secular powers | Last deception |

| Rev 21–22 | New Jerusalem | Transfigured Church | Post-judgment | Eternal kingdom |

Notes

- Asterios Agryriou, Les Exégèses grecques de l’Apocalypse à l’époque turque (1453–1821) (Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies, 1985), 527–586.

- Ibid., 527–530.

- Ibid., 533–534.

- Ibid., 573–574.

- Ibid., 579.

- Ibid., 575–576.

- Ibid., 579–581.

- Ibid., 569–572.

- Augustine, The City of God, trans. Henry Bettenson (London: Penguin, 2003), bk. 20.

- Agryriou, Les Exégèses grecques, 581–583.

- Ibid., 570–571.

- Ibid., 575.

- Ibid., 569–570.

- Ibid., 575–576.

- Ibid., 585.

- Ibid., 583–585.

- Ibid., 584–585.

- Ibid., 585–586.

- Ibid., 569–572.

- Ibid., 571–572.

- Ibid., 583–586.

- Ibid., 579–580.

- Ibid., 585–586.

- Ibid., 586.

- Andrew of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse, PG 106; Arethas of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse, PG 106.