By: Jonathan Photius, The NEO-Historicism Research Project

Introduction

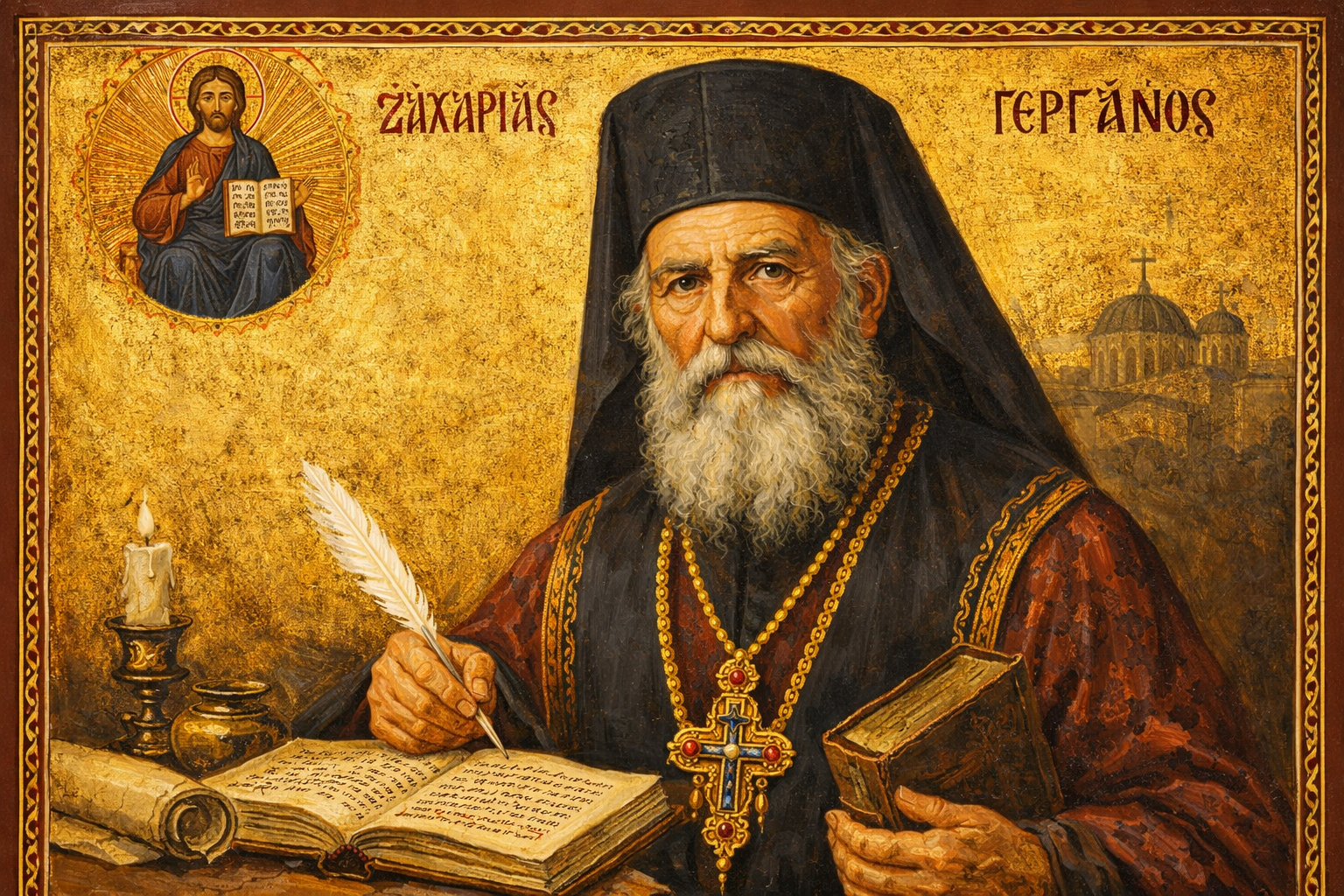

Metropolitan Zacharias Gerganos of Arta occupies a transitional yet decisive place in the formation of post-Byzantine Greek Orthodox interpretation of the Apocalypse. Writing within the inherited Byzantine exegetical tradition while responding to the radically altered historical conditions of Ottoman rule, Gerganos exemplifies the gradual emergence of an Orthodox historicist consciousness—one that reads the Book of Revelation as a theological history of the Church unfolding in time rather than as a speculative map of future events.¹

Unlike later historicists, Gerganos does not seek to systematize prophecy chronologically. His importance lies instead in the conceptual architecture he provides: a restrained but unmistakably historical reading of the Apocalypse that would become normative in later Greek Orthodox commentary.

Education, Formation, and Ecclesiastical Career

Although the surviving biographical data on Zacharias Gerganos is limited, the contours of his life and formation can be reconstructed with reasonable confidence from internal evidence in his writings, his ecclesiastical rank, and comparison with contemporary Orthodox hierarchs of the post-Byzantine world.

Gerganos’ commentary presupposes advanced theological and philological education. His facility with Scripture, patristic exegesis—especially Andrew of Caesarea—conciliar theology, and polemical categories indicates formal training within the Orthodox educational networks of the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. Like many Greek clerics of his generation, he likely studied in one or more major centers of Orthodox learning under Ottoman rule, such as Constantinople, Mount Athos, or a prominent episcopal academy.²

What is certain is that Gerganos rose to the rank of Metropolitan, placing him among the senior hierarchy of the Orthodox Church. In the Ottoman period, metropolitans functioned not only as pastors but as judges, educators, doctrinal guardians, and representatives of Orthodox communities before imperial authorities. This episcopal vocation profoundly shapes Gerganos’ exegetical tone: measured, ecclesial, and pastorally oriented rather than speculative or sensational.

The Commentary as a Late-Life Synthesis

Internal evidence strongly suggests that Gerganos composed his commentary on the Apocalypse late in life, after decades of ecclesiastical service. The work bears the marks of mature reflection rather than youthful experimentation. The Apocalypse is not treated as a puzzle awaiting solution, but as a reality already experienced by the Church.

This is the voice of an elder hierarch interpreting Scripture through lived history. The emphasis falls on synthesis: drawing together patristic tradition, historical suffering, and pastoral exhortation. In this respect, Gerganos anticipates later figures such as John Lindios and Apostolos Makrakis, whose mature writings similarly function as summative theological testimonies rather than speculative treatises.

The Apocalypse as Ecclesial History

Gerganos approaches Revelation as a book addressed to the Church across time, not to a distant end-time generation. Like Andrew of Caesarea, he reads symbolically and ecclesially; unlike Andrew, he applies those symbols explicitly to post-Byzantine historical realities.³

As Les Exégèses demonstrates, this period witnesses a decisive shift in Greek Orthodox exegesis: the Apocalypse increasingly becomes a mirror of ecclesial history under divine providence.⁴ Gerganos belongs to the earliest generation in which this historical application becomes methodologically legitimate while remaining firmly grounded in patristic theology.

Apocalyptic Adversaries: Papacy, Islam, and the Beasts of Revelation

A defining contribution of Gerganos’ commentary is his articulation—still restrained, but unmistakable—of a dual adversarial framework that would become standard in Greek Orthodox historicism.

The Beast from the Sea: Imperial Persecution

Following Byzantine precedent, Gerganos identifies the Beast from the Sea (Rev. 13:1) with hostile imperial power rather than a future individual tyrant. In the post-Byzantine context, this corresponds most naturally to Islamic political domination, characterized by coercive authority over Christian populations, persecution, taxation, and the suppression of Orthodox sovereignty.

As Les Exégèses notes, post-Byzantine commentators increasingly interpreted Islamic rule as a divinely permitted chastisement rather than a purely demonic anomaly.⁵ Gerganos reflects this providential realism: Islam functions as a historical instrument fulfilling an apocalyptic role long anticipated by the Fathers.

The Beast from the Land (False Prophet): Ecclesial Corruption

More consequential for later tradition is Gerganos’ interpretation of the second beast, later named the False Prophet. Here he aligns with an emerging Orthodox consensus by associating this figure with Latin ecclesiastical authority, particularly the Papacy.

The land beast is dangerous precisely because it resembles Christian authority. It speaks religiously, claims jurisdiction over conscience and doctrine, and redirects ecclesial allegiance away from the conciliar and apostolic structure of the Church. For Gerganos, this represents a deeper spiritual danger than external persecution.

The Name and Number of the Beast: 666 and λατεῖνος

In his interpretation of Revelation 13:18, Zacharias Gerganos explicitly follows the ancient patristic tradition associated with Irenaeus by identifying the name of the Beast as λατεῖνος (“the Latin one”), whose numerical value equals 666.⁶ Unlike Irenaeus, however, who presents this identification cautiously and without definitive historical application, Gerganos applies it decisively within his own ecclesial context.

For Gerganos, λατεῖνος does not denote ancient pagan Rome or a generic ethnic designation. Rather, it signifies the Latin ecclesiastical system centered in Rome, that is, the Roman Catholic Church as it existed in separation from Orthodox conciliar catholicity. The number 666 thus designates not an individual Antichrist, but an institutional form of authority that imitates universality while lacking apostolic and conciliar legitimacy.

This interpretation represents a significant development in Orthodox apocalyptic exegesis. Writing after the Great Schism, the Crusades, and centuries of Latin-Orthodox conflict, Gerganos no longer leaves patristic symbols suspended as theoretical possibilities. Instead, he historicizes them responsibly, applying them to the concrete ecclesial realities of his time. The Beast’s name marks a system that speaks in Christian language, claims spiritual authority, and yet diverts ecclesial allegiance away from the true catholic structure of the Church.

By affirming λατεῖνος as a present historical referent rather than a speculative future possibility, Gerganos advances Orthodox interpretation beyond patristic reserve into measured historicist application, while remaining fully grounded in the Fathers.

Gerganos and the Formation of Greek Historicism

The enduring importance of Zacharias Gerganos lies in what his commentary makes possible.

First, he normalizes a dual-enemy paradigm: Islam as persecuting empire and Latinism as ecclesial distortion. Second, he firmly establishes an institutional understanding of Antichrist, identifying the beasts and 666 with historical systems rather than future individuals. Third, he preserves a pastoral orientation, ensuring that historical interpretation serves repentance and vigilance rather than speculation.

Finally, although Gerganos does not develop chronological systems, his historical reading of Revelation creates the conceptual space in which later figures—Christophoros Angelos, Anastasios Gordios, John Lindios, and ultimately Apostolos Makrakis—would introduce chronology without abandoning Orthodox theology.⁷

Conclusion

Zacharias Gerganos stands as a crucial bridge between Byzantine symbolic exegesis and modern Greek Orthodox historicism. His education rooted him in patristic tradition; his episcopal office imparted restraint and authority; his lived experience of post-Byzantine suffering grounded his historical interpretation; and his explicit identification of λατεῖνος with Latin ecclesial authority marked a decisive step in the historicist application of the Apocalypse.

In recovering Gerganos, we recover not a marginal figure, but a foundational voice in an Orthodox tradition that reads Revelation as the lived history of the Body of Christ under divine providence.

Footnotes

- Asterios Agyriou, Les Exégèses de l’Apocalypse dans la tradition grecque (Athens: Institut Français d’Athènes, 1985), introduction.

- Ibid., chap. on post-Byzantine exegetes.

- Andrew of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse; cf. Agyriou, Les Exégèses, Byzantine section.

- Agyriou, Les Exégèses, methodological synthesis.

- Ibid., discussion of Islam in post-Byzantine apocalyptic interpretation.

- Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses V.30.3; see Agyriou, Les Exégèses, treatment of 666 and λατεῖνος in Greek tradition.

- Agyriou, Les Exégèses, comparative conclusions.